How the Royal Society of Literature turned into a diversity bloodbath

There has been outrage, backbiting, leaks and claims that the organisation is on the brink of collapse... As the RSL debates the findings of its governance report, former Booker Prize judge Rowan Pelling looks at what led the beautiful world of books to spiral into ugly chaos

For British authors, becoming a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature (RSL) has long meant that your most illustrious peers have agreed that you have written at least two works of exceptional literary merit. Wordsmiths as different as Nick Cave, JK Rowling, and former archbishop Rowan Williams are recent fellows. Once formally invited, the writer attends a ceremony where they select the pen of a deceased luminary (Lord Byron, George Eliot, or even Charles Dickens’ quill) to sign their name into the Roll Book of Fellows. They are then eligible to mingle at the annual RSL summer party with the likes of Monica Ali, Zadie Smith, Ian McEwan, and Kazuo Ishiguro.

For more than 200 years, the RSL, founded in 1820, has glided along like a Jane Austen tea party. Established under George IV, the early presidents included bishops, a prince, a baron, and an earl. Tory grandee Rab Butler was one long-serving president, as was Roy Jenkins. But while the society’s early history reads like an established old boys’ club, things gradually evolved.

In 1908, the first women fellows, Alice Meynell and Margaret Woods, were elected. In the 1960s, the RSL officially became a charity, and finally, in 2017, it had its first woman president, Marina Warner. For years, the society was based in an elegant building on Hyde Park Gate — “like walking into a Turgenev novel,” one insider told me. However, failing to secure the lease, it has since moved to more modest quarters in Somerset House, while its archive was sold to Cambridge University Library.

All these changes, however, feel minuscule compared to the seismic shifts and controversies of recent years, setting the scene for a stormy annual general meeting on Wednesday. There has been outrage, backbiting, copious leaks, and claims that the organisation was on the brink of collapse.

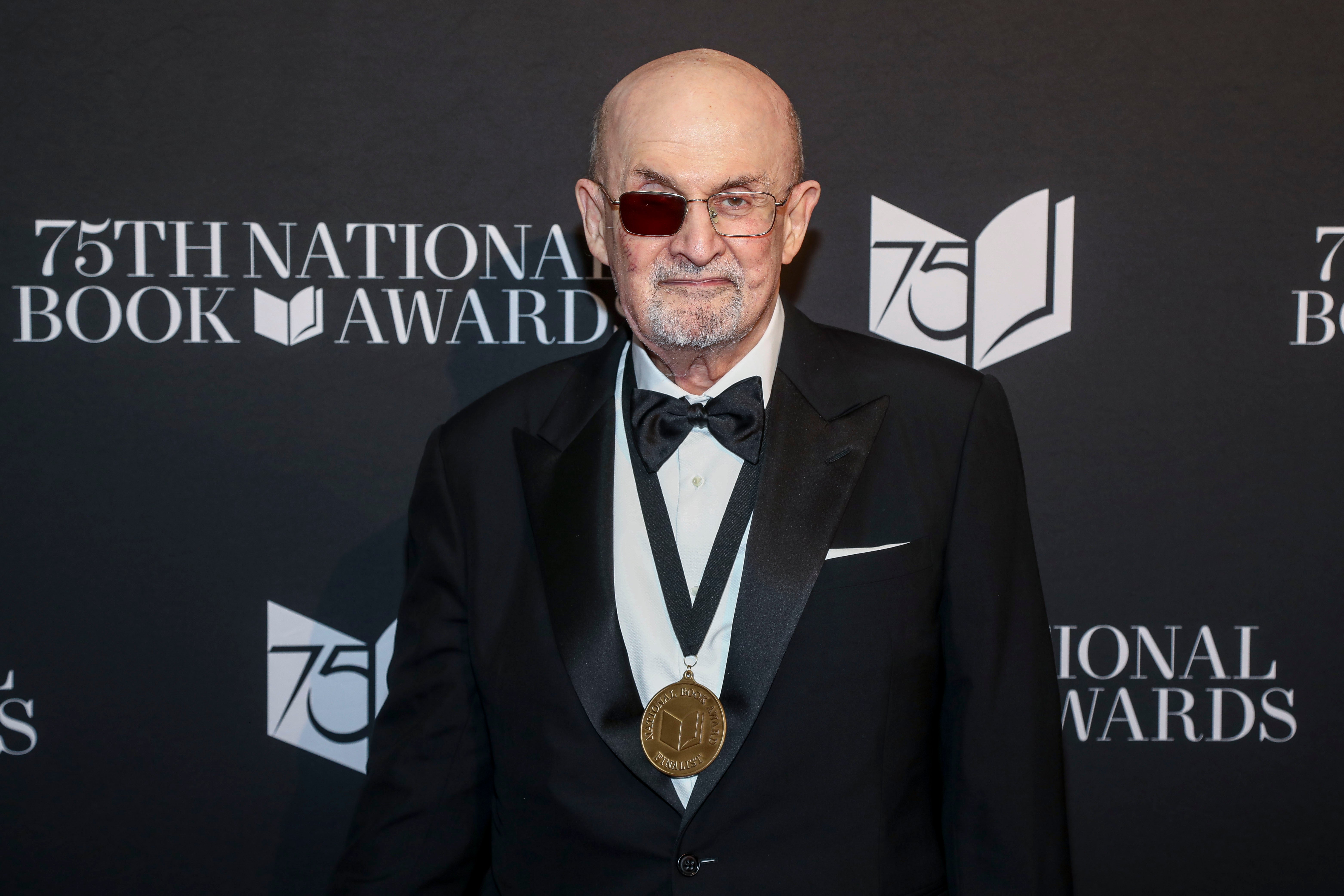

There was fury among fellows at the RSL’s decision not to issue a statement of support for Salman Rushdie after he was stabbed – something felt especially keenly by older members who had risked their safety to support Rushdie when the original fatwa was issued.

There has also been backlash over initiatives to make the fellowship more inclusive and representative. In 2018, a “40 Under 40” drive was launched, aiming to “welcome a new generation of UK writers into the RSL”, with a panel chaired by novelist Kamila Shamsie.

A number of fellows complained that the criterion of excellence was being diluted and were appalled when the reading public was invited to nominate writers they felt had been overlooked. One infuriated fellow said to me: “You open it up wider and wider until you’re in an all-must-have-prizes situation, and there is no merit left.” The novelist and critic Philip Hensher declared: “It’s truly appalling to watch one of the most inclusive and generous organisations in the country be turned into a resentful and exclusive little club by this tiny clique.”

Another controversy involved an issue of the RSL’s magazine being pulled over what insiders claimed was censorship of an article on the Palestine Festival of Literature that had criticised Israel. The magazine was eventually published, but its long-time editor Maggie Fergusson was let go.

Many also deplored the society’s failure to defend fellow Kate Clanchy, who faced a torrent of online abuse when accused of using racial stereotyping in her award-winning book Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me. While the pupils she wrote about defended her, Clanchy resigned from the RSL after one of her fiercest critics was selected as a fellow.

Private Eye described these events as “an ideological purity spiral” disguised as a diversity drive. However, RSL modernisers would argue that the summer party now looks markedly less like an elderly Oxbridge academic’s farewell bash than it used to. I know because I attended the first post-lockdown bash in 2022 with newly elected fellow Monique Roffey, fresh from winning the 2021 Costa Award for Best Overall Book with her novel The Mermaid of Black Conch.

Roffey told me how thrilled she had been to be invited as “an outsider in UK literary circles”, but how it was now “very painful to hear about the resistance to a whole batch of new writers being invited”. She said: “Today, I go to RSL meetings and parties and see my generation of writers represented. I don’t feel like such an outsider. Surely more diversity must be celebrated and embraced as a very positive thing?”

Following a tense year, it was revealed last week that RSL director Molly Rosenberg will leave to “pursue new career opportunities”, and chair Daljit Nagra will step down at the AGM after a four-year tenure.

This may satisfy the 65-plus group, which makes up over half the current membership but, behind the scenes, many younger fellows believe Rosenberg was unfairly maligned. Under her tenure, six new RSL awards and prizes were established (including the Sky Arts RSL Writers Award and Jerwood Poetry Award), women’s pens were used for the first time in the signing ceremony, and the number of vice presidents doubled to include writers like Jackie Kay, Mary Beard, and Simon Armitage. Rosenberg also launched RSL 200, a bicentenary festival that ran for five years and included many high-profile events.

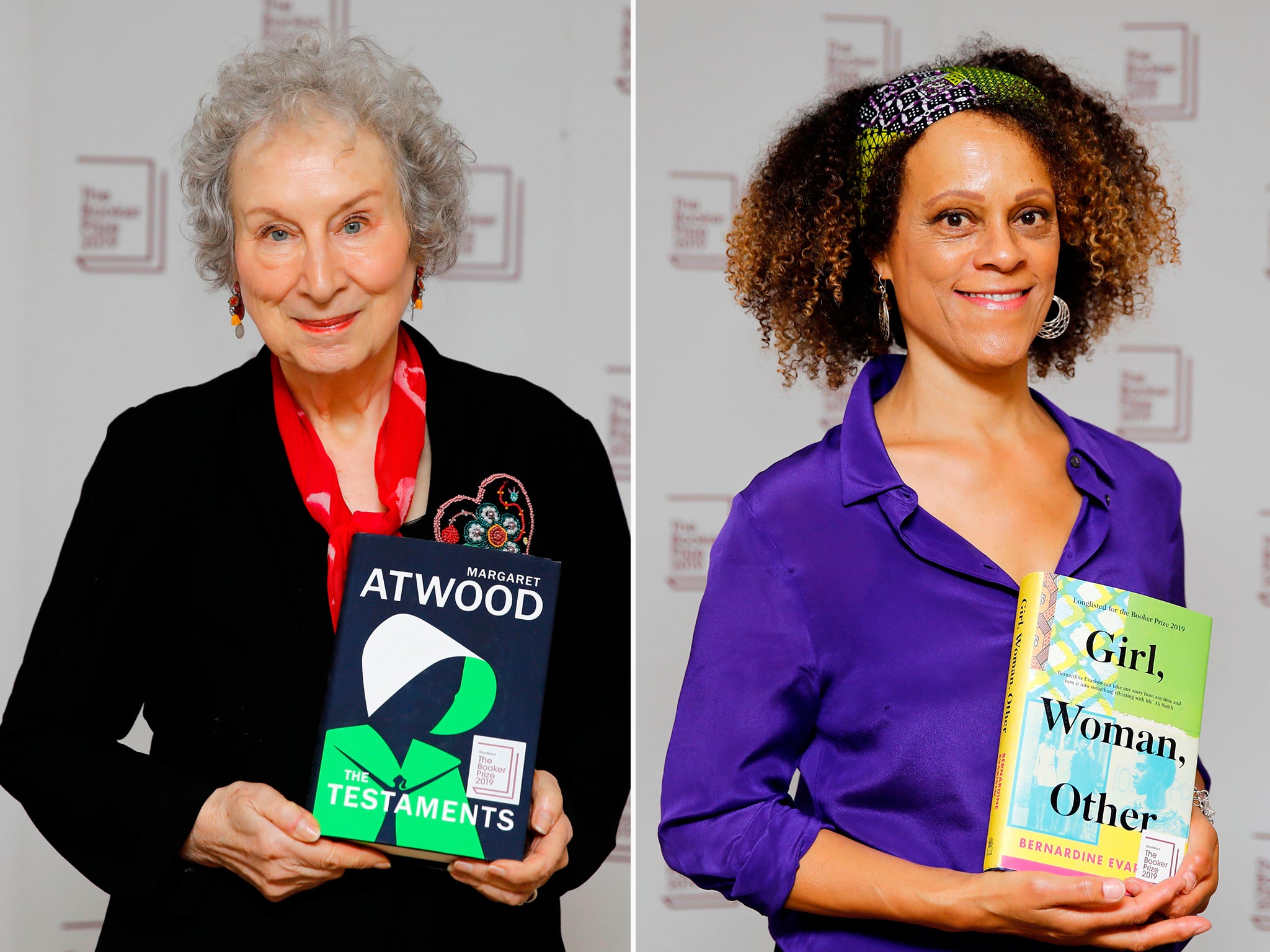

The RSL’s current president, Bernardine Evaristo, defended the society and Rosenberg over the Clanchy and Rushdie incidents, stating: “The society has a remit to be a voice for literature, not to present itself as ‘the voice’ of its 700 fellows.” (It’s worth noting Evaristo issued a personal message in support of Rushdie.)

But therein lies the problem: the fellows don’t seem to agree on what the RSL’s “remit” should be. Is it a place for the crème de la crème of British literature to meet and celebrate? Or is it a campaigning group advocating for writers and contemporary literature? Is it a refuge for those who immerse themselves imaginatively in other people’s experiences? Or should it have an explicit obligation to reflect societal changes and represent diversity?

One thing became clear to those intimately involved: the RSL is a Georgian society grappling with a 21st-century culture for which it isn’t structured or equipped. At the much-anticipated AGM, the findings of the society’s first-ever governance review will be presented and debated, and tempers may well boil over.

For gossipy, book-loving outsiders like me, the internal struggles have opened some fascinating lines of inquiry. Anyone can visit the RSL’s website to see who is – and isn’t – a fellow. Multi-million-selling Ken Follett is; multi-million-selling Matt Haig is not. Nor is Christie Watson, despite her Costa-winning debut novel, heart-piercing memoirs on frontline nursing, and professorship at UEA. Where’s comic writer Craig Brown after winning the Baillie Gifford prize? Or are old Etonians now barred?

No selection panel can please everyone. Literary spats are notorious (I’m still mulling over Tibor Fischer declaring in 2003 that Martin Amis’s novel Yellow Dog was so “terrible” it was “like your favourite uncle being caught in a school playground, masturbating”) and often outlive the novels or writers they concern. I was a Booker Prize judge in 2004, and a few authors cold-shouldered me for years afterwards, believing it was my silly fault they didn’t win.

The RSL storm starkly illuminates the wider struggles in the publishing world. Many older, established authors aren’t receiving the advances or sales they once took for granted. This inhospitable landscape coincides with publishers launching initiatives to find young, diverse writers from ethnic minority or socially deprived backgrounds.

Those who once ruled the literary roost feel they are being pushed off their perch, much like the middle-aged and middle-class complain about the same thing happening in the business world. Culture wars rage, from gender-critical views to “tainted” investments linked to everything from Israel to oil. Ethical purity has led to literary festivals losing funding and many authors losing friends and influence.

This collision has affected every antiquated British institution. The Garrick Club was dragged into the 21st century when its governing body realised barring women from membership was leading to mass resignations. Oxford and Cambridge are under constant scrutiny for their overrepresentation of elite school students. The cries of agony are audible everywhere, like a sadistic dentist has been let loose on bastions of privilege.

My prediction is that, whatever happens at Wednesday’s AGM, the most painful part of the RSL’s transformation has been weathered. No one, on either side, wants the society to collapse. If there’s one thing worse for a writer than not being a fellow, it’s the prospect of never getting to flourish your signature with Byron’s pen.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments