Decolonising Shakespeare makes no sense for this simple reason

Bard bashing has become something of a national sport, says Robert McCrum, and the latest attempt to rewrite the legacy of our most successful playwright shows a profound misunderstanding of who or what Shakespeare was as an artist

No question: something is “rotten in the state of Denmark” when one of Britain’s redtops splashes on its front page with WOKEO & JULIET in 60-point caps. What’s going on? Ostensibly against “trigger warnings” at the Globe, this broadside comes in the contemporary context of a wider and more bitter row about William Shakespeare’s canon. For some years now, there’s been a steady drumbeat within education for a refocusing of the curriculum, to “teach Shakespeare differently”. Or, in the weasel words of one teacher, “to teach students, through literature, to challenge the status quo”.

This week, the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, a well-meaning research and promotional institute, announced that it was to “decolonise its museum collections” to tackle the claim that the playwright’s legacy promotes “white supremacy”.

It feels something like Woke’s Last Stand. Mind-to-mind combat between the crusty, “tosh”-spouting defenders of a hallowed literary tradition versus (as they see it) the doctrinaire enemies of Shakespeare, the “universal” genius, led by Helen Hopkins of Birmingham University who wrote the latest decolonisation report. All this is – as the poet himself might have put it – “hot ice and wondrous strange snow”.

Adventures first; explanations second. Shakespeare himself would view this brouhaha with a sceptical, slightly mystified expression. As the most famous and successful playwright of Elizabethan England, he’s the most semi-detached author imaginable, certainly by 21st-century standards, never troubled by book prizes, literary festivals or X (Twitter). Not that he was any kind of slacker.

Every day of his adult working life must have been devoted either to running the Globe, and writing two or more plays a year, together with poetry such as his “Sugar’d Sonnets” for his aristocratic and royal patrons.

Nevertheless, it was not until he was well into the second decade of his career that he paid much attention to the printed editions of his work. These quartos, in turn, were slow to identify “W Shakspere”. As Stephen Greenblatt, author of Will in the World, has put it, Shakespeare always wrote “as if he thought there were more interesting (or at least more dramatic) things in life to do than write plays”.

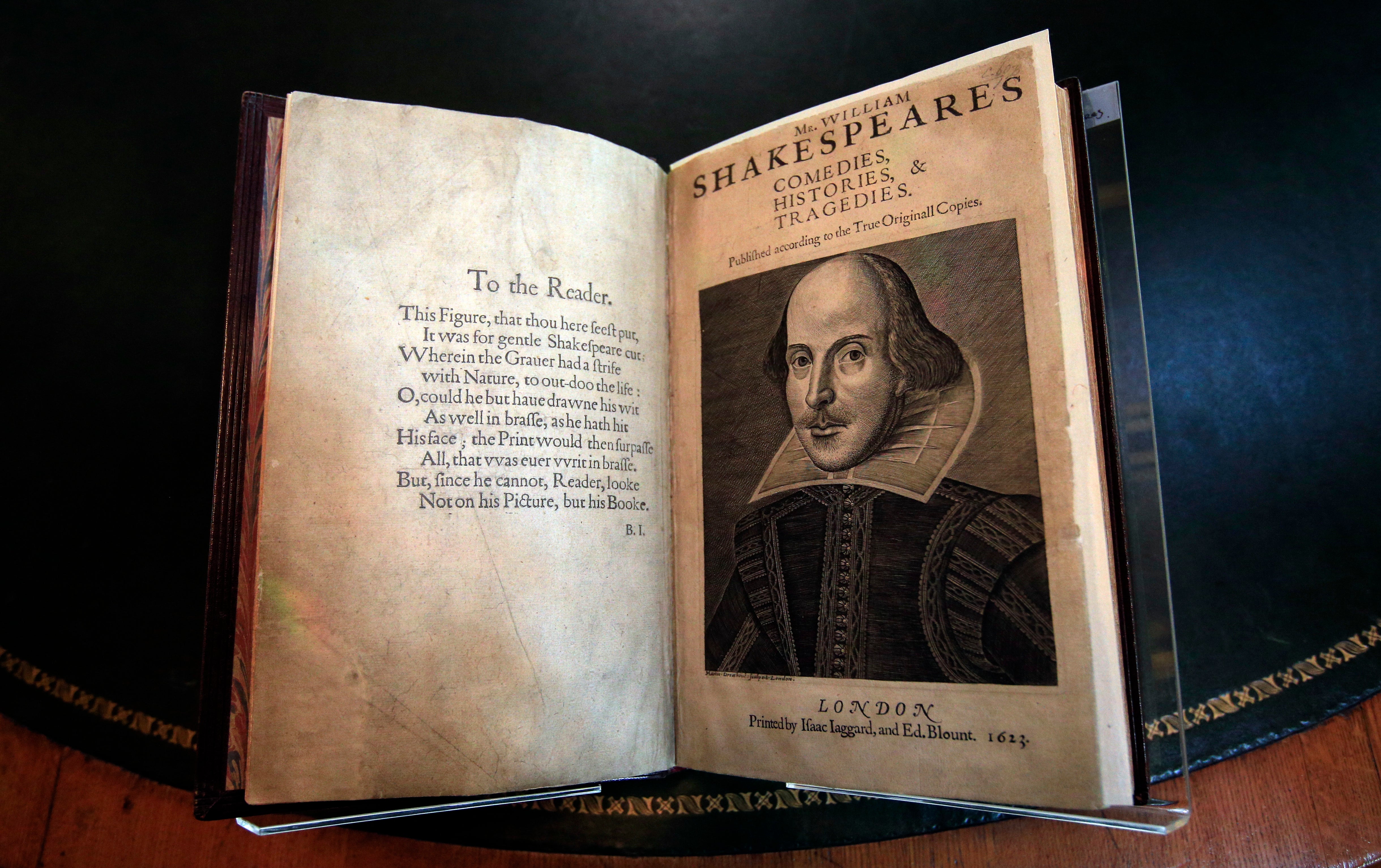

There is, however, no getting away from Shakespeare’s absolute supremacy as a poet and playwright. Even Ben Jonson, his most assiduous rival, was forced to concede, on the publication of the First Folio in 1623, that his great contemporary was the “soul of the age”.

Later, it would be the high Victorian poet Matthew Arnold who pronounced that “Others abide our question, thou art free.” Sorry, but at the Birthplace Trust, he’s not. And here’s the thing: this is not new, not by a long chalk. He has been “cabined, cribbed, confined” before, always vulnerable to the “whirligig of time”.

The first 200 years of his afterlife are marked by successive outbreaks of interference, first from the Puritan revolution which drove his works underground and next from another generation of prudes and bowdlerisers for whom the perceived coarse vulgarity of his work was offensive. In mood, if not in substance, the latest woke chapters of Birmingham University would find lots to discuss with Nahum Tate, an Irish poet and playwright who, notoriously, devised a happy ending for King Lear in which Cordelia gets married to Edgar. Nor was Tate alone. The poet laureate John Dryden also conceived The Enchanted Island as a “comedy” version of The Tempest.

In this context, the “decolonisers” merely want to view these plays through a narrow lens. It’s inevitable that some of their more untethered comments will provoke the rage of middle England. But to Professor James Shapiro, the bestselling American Shakespeare scholar, these disrupted times mark a season of intense and timely renewal. “Shakespeare is being embraced. What’s happening is exciting. Right now we’re going through a period where race matters,” he says. “To those who are complaining, and are disturbed by the current focus, I’d give it 10 years.”

Indeed, on the London stage, some of the so-called decolonisers’ concerns have already been addressed by innovative young directors. In 2024, the sell-out Donmar production of Macbeth starred Cush Jumbo as Lady Macbeth, with colour-blind casting throughout the ensemble. The Globe never misses an opportunity to reinterpret and reframe his works through a progressive lens. But considering Shakespeare’s honoured place before audiences in China and Japan, the Middle East, North and South America, and most of Europe, it’s hard not to conclude that there is a distressingly “little England” tenor to some of the decolonisers’ arguments.

Further, the strictures of identity politics towards some RSC and NT productions ignore the degree to which non-English audiences revere some of our productions precisely because they are so quintessentially English. The poet WH Auden used to say that it was the business of our writers to “commune with the dead”, to engage in a dialogue with the creative past. Shakespeare himself communed with Spenser and Marlowe; followed by Milton, Johnson, Pope, Keats, and Coleridge all in thrall to Shakespeare. It’s a trend that’s gone on to the present day. Once we cease to treasure a dialogue with the dead, we run the risk of finding ourselves in a morgue.

To my mind, there’s something well meaning, but misguided, about this decolonisation initiative that is fundamentally at odds with who and what William Shakespeare was as an artist. He was a very clever man and a writer of genius (not necessarily the same thing) who was very lucky. Despite some perilous politics, he was never racked, or seriously threatened. Besides, no one could ever ask him to withdraw from, or betray, his own self because no one knew where to find it – and he wasn’t saying.

Always the zen master of “negligent ambiguity”, Iago’s “demand me nothing” hints at the fiery solitude of the poet’s mind for whom close personal scrutiny was no laughing matter. He remained a writer and a true artist, never in thrall to one kind of politics, identity or otherwise. Instead, he ingested the enthralling variety of the world around him. His spirit as an omnivore makes him uniquely seductive, and innately slippery: witty, sophisticated, wise and – from page to page – the most wonderful company.

He would have been mystified by these decolonisers. His immense gifts were part of himself, and that self was never mortgaged, banged up, or bankrupted. It’s as if, very early, Will Shakespeare took an oath of loyalty to his calling and its craft. He would never perjure that vow. He did not have to: his commitment to that precious gift, his “imagination” and its free traffic, made him a free man, in a very English way.

Robert McCrum is the author of ‘Shakespearean: On Life & Language in Times of Disruption’ published by Picador

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments