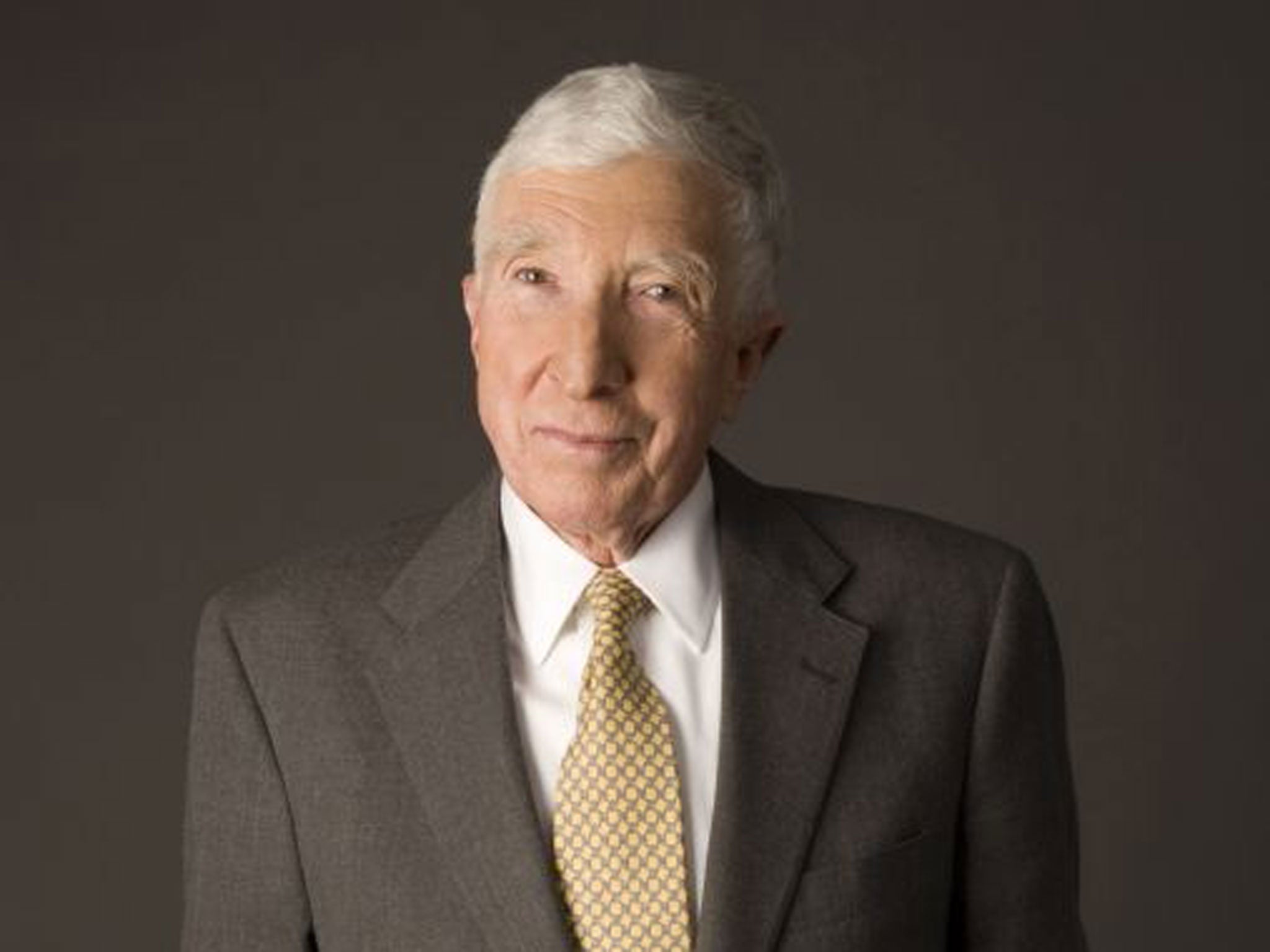

Rabbit Series by John Updike, book of a lifetime

David Baddiel praises Updike's great four-act opera of the beautiful mundane

I read Rabbit out of order. It's four books – four and a half, if you include the late novella, Rabbit Remembered – each one written at the end of a decade, between 1960 and 1990: Rabbit, Run, Rabbit Redux, Rabbit Is Rich and Rabbit At Rest. But I didn't know that when, in WH Smith in Brent Cross circa 1988, I picked up Is Rich, read one sentence and thought "well obviously I'm buying this". When I found out that there were two prequels to that book, I was simultaeneously dismayed – like someone who realises he has somewhat spoiled Back To The Future's 1 and 2 by watching 3 first – and excited, because it meant there was so much more yet to read.

When people talk about Updike, they tend to mention first off, the prose. You see a lot of adjectives attached to descriptions of Updike's prose – shimmering, burnished, that kind of thing – and indeed, he is the greatest stylist in American literature, greater even than Faulkner or Fitzgerald. But that focus on the prose tends towards an idea of Updike as a purveyor of beauty without substance, whereas in fact, his writing, however lyrical, is always at the service of character. And character, in Updike, is always complex. For example: in Rabbit, Redux, when Harry's father-in-law informs him that his wife Janice is having an affair, where a lesser novelist would simply make their central character's reaction angry or jealous, Updike tells us that "a hopeful coldness inside him grows…the news isn't all in: a new combination might break it open, this stale peace."

When I'm asked why I prefer Updike to Bellow and Roth, the short answer is: Harry Angstrom. Bellow and Roth – particularly Bellow – could only write characters like themselves: academics, intellectuals, writers, men possessed of great linguistic power. Harry is a Toyota car salesman. His politics are fairly reactionary, his attitude to women and children unprogressive. He is not an articulate man: as such, he's the opposite of Updike.

And yet, by incredible literary sleight of hand – by sliding in and out of Harry's point of view, and by describing what Harry is thinking in ways that Harry himself could not describe – Updike is able to make this ordinary bloke into a great seer, a prism through which all life can be refracted. It's an unrivalled literary magic trick.

Soon after reading Rabbit for the first time, I read elsewhere Updike's mantra, which is that he considered that the object of his work was "to give the mundane it's beautiful due". I think that's a fantastic mission statement for art: and anyone who agrees must read Rabbit, John Updike's masterpiece, his great four-act opera of the beautiful mundane.

David Baddiel's latest book is 'The Parent Agency' (HarperCollins)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments