There was a darkness behind the film’s frivolity – Merchant Ivory and the making of A Room with a View

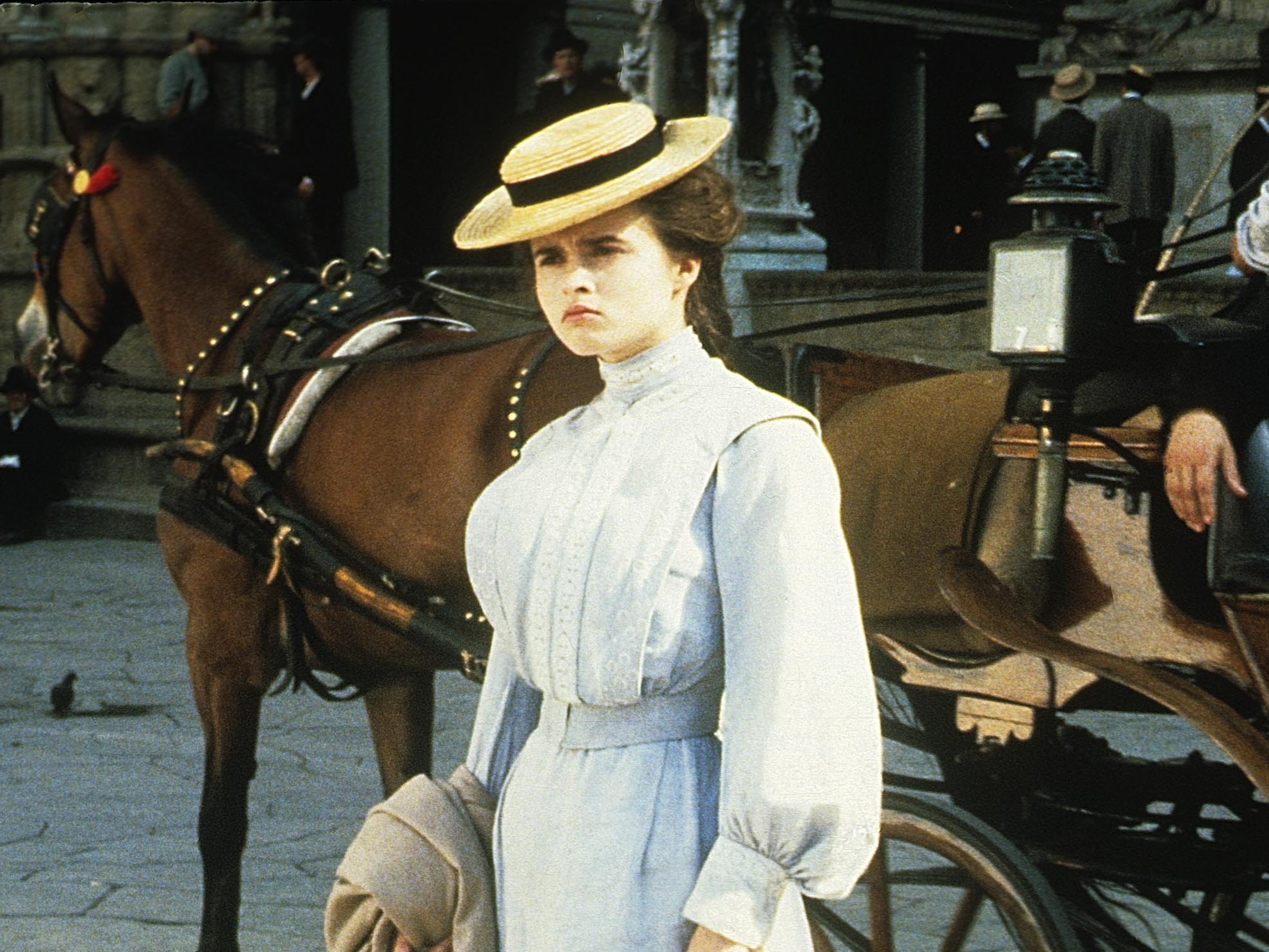

It starred the late Julian Sands as the dashing George Emerson, sparked the career of an 18-year old Helena Bonham Carter and was derided for being ‘Laura Ashley cinema’. What, asks Geoffrey Macnab, is it about the romantic comedy of manners ‘A Room with a View’ that still resonates so strongly with audiences?

There is a moment early on in Merchant Ivory’s comedy of manners A Room with a View that has an obvious added poignance when you watch it today. The 1985 film, adapted from the EM Forster novel, opens in the summer of 1907. We are deep in the Italian countryside. The dashing, freethinking George Emerson (Julian Sands), on holiday in Florence with his retired journalist father (Denholm Elliott), has just impulsively kissed Lucy Honeychurch (Helena Bonham Carter) in a field.

Director James Ivory shoots the scene in a deliberately overblown fashion. Romantic opera music blasts away on the soundtrack as the young lovers, both dressed in white, enjoy their illicit embrace amid the tall grass and poppies. But then we hear the strident voice of the chaperone, Charlotte (Maggie Smith), who has stumbled on to the scene. “Lucy!” Charlotte shrieks and the romantic spell is broken. Lucy beats a furtive retreat. Moments later, everybody heads back to town in their carriages, but George stays behind saying he will walk. As he strides off alone, a violent storm suddenly breaks around him.

Earlier this week, when it was finally confirmed that Sands had died after going on a solitary hike in January on Mount Baldy in California, A Room with a View was the first film cited in almost every obituary of the actor. This was the only movie Sands made with Merchant Ivory, and yet, you could easily be forgiven for thinking he was a permanent part of their repertory company.

What is it about an Edwardian costume drama, made during the height of the Thatcher era and loathed by many critics for its perceived snobbery and complacency, that still resonates so strongly with audiences? In hindsight, the answer is partly obvious. Films such as A Room with a View, Maurice (1987) and Howards End (1992) helped launch the careers of some of British cinema’s best-known actors. Sands, Bonham Carter, Rupert Graves, Hugh Grant, Daniel Day-Lewis and Emma Thompson all had important early roles in Merchant Ivory projects.

At the same time as they were showcasing new talent, producer Ismail Merchant and director Ivory also gave plum parts to established British actors like Anthony Hopkins, Maggie Smith and Denholm Elliott.

In interviews, Ivory often credited his casting agent Celestia Fox with identifying the perfect actors for his Forster adaptations, but he had an uncanny knack of bringing the best out of them. Bonham Carter, for example, was utterly distinctive as the mischievous ingenue Lucy in A Room with a View.

As the director later recounted to Robert Emmet Long in the book James Ivory in Conversation, she made an unusual first impression. “She sat scowling on our sofa with her short legs stuck out in front, and her outlandish shoes. But she was very quick, very smart and very beautiful. Though coming from a grand aristocratic family, she had a terrible modern London accent and needed a lot of coaching to get rid of it.”

Much of the film was high-spirited and fun – all picnics, sightseeing and tea and tennis on the lawn, albeit with flashes of violence and darkness. Audiences relished Sands’s dashing, intense performance as George, a sort of Edwardian Heathcliff, and were enchanted by Bonham Carter as the prim but endlessly curious young Englishwoman abroad.

“It’s very hard to walk across a plowed field in high heels, and, oh God, it was hard work. I just knew I had to get to him without falling down. And then not laugh when he kissed me. And it’s really hard to kiss someone when you’re only 18 and you haven’t done it that many times, too. So it was hard, that was hard,” Bonham Carter recalled her smooch in the field with Sands in an interview to mark the film’s 30th anniversary.

You’d have to be a curmudgeon not to enjoy the film’s other most famous scene, that Carry On-style romp in which Sands, Simon Callow (as the liberated Reverend Beebe) and Rupert Graves (as Lucy’s brother Freddy) go skinny dipping together and then have to run away and hide after being disturbed by Lucy’s mother and her entourage.

Day-Lewis, not generally known for his comic performances, was very funny as the supremely conceited and prissy Cecil Vyse, George’s rival for Lucy’s hand in marriage. “He’s the sort of person you imagine you might be in your worst nightmare, desperately, desperately self-conscious and pompous,” Day-Lewis summed up the memorably repellent character on a TV chat show.

It’s really hard to kiss someone when you’re only 18 and you haven’t done it that many times

A Room with a View was described by critics as “effervescent”, “glorious” and “blithely, elegantly funny”. Nonetheless, there was also an immediate backlash against it. The mid-1980s was a rocky period for UK cinema. Thatcher’s government had dispensed with the Eady Levy (a tax on cinema tickets that helped fund production). Very few films were being made. Cinema admissions in 1984 were at 54 million, an all-time low until the Covid pandemic.

The plight of the industry exacerbated the resentment felt toward Merchant Ivory Productions. While other filmmakers were scraping together their budgets, Ivory and his crew were off in Italy, seeing the sights. Whereas Stephen Frears’ My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), a contemporary drama about the love affair between a white punk (Danny Day-Lewis) and a British south Asian man (Gordon Warnecke), seemed to reflect the sexual, racial and political tensions of the period, A Room with a View was regarded by its detractors as empty escapism. It was just too pretty, too painterly and too full of characters in suits and long dresses.

Bugsy Malone and Evita director Alan Parker, a working-class filmmaker from north London, famously derided Merchant Ivory movies as coming from “the Laura Ashley school of filmmaking”. Even critics who enjoyed A Room with a View did so grudgingly. “A long, slow, lingering, lazy, dream look at a slice of Victorian life so vivid and lovely you can smell the roses and feel the rain”, rhapsodised TheDaily Mirror’s reviewer who then, as if embarrassed by his own purple prose, quickly warned his readers that the film may well also “bore the pantaloons off them”.

In fact, the Merchant Ivory films were far more barbed and caustic than certain critics seemed to notice. They probed away relentlessly at the snobbery and cruelty of their upper-class characters. They weren’t easy to finance either. When Ismail Merchant pitched A Room with a View to Hollywood mogul Samuel Goldwyn, he was told that “the characters should be made into Americans”.

Goldcrest eventually came in to back the movie but, as Jake Eberts and Terry Ilott wrote in their book My Indecision is Final, the film “did not inspire any great enthusiasm” among the Goldcrest management team. They got behind it simply because it seemed a “safe bet” and they needed to find something to put their money into.

Ironically, Merchant Ivory were attacked both for making stuffy British costume dramas and for not being British enough. As film historian Alexander Walker noted in his book National Heroes, not one of the “creative troika” behind their movies was from the UK., Ivory was American, Merchant was Indian and their redoubtable screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala was German-born. She became a British citizen after the Second World War but spent much of her life in India and the US. Public film funders were therefore very wary about investing in their movies

Also often overlooked was the fact that the Merchant Ivory costume dramas constituted only a small part of their overall output. They made films in India, the US, France and Shanghai as well as in England. The 95-year-old Ivory’s latest film, A Cooler Climate (2022), which he co-directed with editor Giles Gardner, is a feature documentary based around footage that Ivory shot as a young man in Afghanistan, where he travelled in 1960, long before the Soviet invasion or the arrival of the Taliban.

A Cooler Climate shares certain qualities with A Room with a View. It may be a travelogue and its subject may be the director himself but it is another of Ivory’s coming-of-age stories about a young adult at a key formative part of his or her life.

Ivory is a complex and guarded figure who sometimes behaved waspishly on set. Judi Dench wasn’t at all complimentary about his behaviour toward her during the making of A Room with a View and told film historian Brian McFarlane that she disliked working with him. “I didn’t feel that I was on his wavelength, and I didn’t feel that he wanted me in the film,” she stated. Dench plays the flighty English romantic novelist Eleanor Lavish whom Lucy meets in Florence. In what Dench felt was one of her best scenes, Eleanor “goes mad and attacks the man selling postcards” in the square. Ivory congratulated her about her work in the scene but then, to her disappointment, cut it out of the final movie without providing a satisfactory explanation. “He told me that Helena Bonham Carter hadn’t been feeling up to it that day.”

The American director isn’t above a little petty score-settling either. His 2021 memoir Solid Ivory has a curious chapter on Call Me By Your Name (2017), the Luca Guadagnino coming-of-age romantic drama about a summer love affair between a young man, Elio (Timothée Chalamet), and his father’s assistant, Oliver (Armie Hammer). The project, which he took on casually, as a favour for friends, turned into one of Ivory’s greatest late triumphs. At the ripe old age of 89, he won an Oscar for his screenplay. However, he had originally been asked by Guadagnino to co-direct the movie and was clearly upset about the manner in which he was “dropped”.

“It destroyed the life…that I hoped to have again in Italy, a country I love and can never have enough of,” he wrote of his reaction when he learnt that he was no longer welcome on set.

Ivory also criticised the lack of full-frontal male nudity in the film and claimed that the lovemaking was described in far more explicit fashion in his screenplay for the movie.

On one level, Call Me By Your Name is a companion piece to A Room with a View, the film he had gone to his beloved Italy to shoot 30 years before – and which did have full-frontal male nudity, at least very fleetingly. Guadagnino’s movie may be a long way removed from the Edwardian world explored in Ivory’s adaptation of EM Forster’s novel, but they’re both summer romances made with the same youthful zest and irreverence – and with the same love of Italian landscape, art and antiquity. You could easily imagine Julian Sands being cast as Oliver. He gave arguably the most vivid performance of his career in A Room with a View, while the other actors, young and old (with the exception of Dench), looked as if they had never enjoyed themselves so much in front of a camera.

“It attracted teenage girls all over the world as well as intellectuals, nostalgia buffs and people who were crazy about Italy,” Ivory observed to Long of a movie that has easily outlasted all those gritty social realist dramas to which it was compared so unfavourably when it first appeared. Ivory may have a reputation as a caustic and reserved figure but, with A Room with a View, he somehow made one of the biggest crowd-pleasers of the 1980s – a film that has never gone out of circulation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments