‘A sibling’s suicide is like an explosion going off in slow motion’

When novelist Richard Mason’s sister died, he says it broke something that he never really recovered from. But, he tells Megan Lloyd Davies, through tragedy and his own experiences with depression he has created a foundation which has transformed so many other lives

It’s tempting to read Richard Mason’s life like one of his fictional characters. Elite education, book deal at university and more than three million copies of his first novel sold. Twenty-five years on, he’s published four more acclaimed novels and we talk while he’s in Australia researching a new show for Apple. So far, so gilded.

But our initial Zoom conversation is also cancelled because Cyclone Alfred is battering eastern Australia and Mason has had to flee the place he was staying after a fire broke out. Our second attempt cuts out midway when power lines go down.

It’s a neat encapsulation of two themes – one part charmed life, the other seemingly out-of-the-blue destruction with traceable roots – that sum up Mason’s life. Running in tandem with all the success and acclaim is a story of intergenerational mental illness, anguish and his beloved sister Kay’s suicide.

“A sibling’s suicide is like an explosion going off in slow motion because there’s the original blast and then the ripple effects that go very, very, very slowly over decades through the people who are left,” Mason says when we finally talk.

He rarely gives interviews any more. In the year after his first novel, The Drowning People, was published to huge hype in 1999, he spoke to 1,800 journalists, travelled internationally and was featured in Vogue. At just 21, it left him exhausted and suffering crippling panic attacks.

“Our civilisation says you’ll be happy if you’re famous, but I absolutely hated it and thought I was going crazy because I had all those things I’d been told I should want. But the fun wears off very quickly and then you’re just left with the relentlessness of it. These days, I value my privacy.”

We’re talking because the Kay Mason Foundation – the charity he set up in his sister’s name to help children born in the toughest circumstances become transformative leaders – is having a fundraiser in London on 20 March. There’s also an online public auction of lots including two appearances in season two of Day of the Jackal, a game of tennis and lunch at Wimbledon with Bear Grylls and personal shopping with ex-Vogue editor Alexandra Shulman.

However starry it sounds, Mason’s motivation remains deeply personal.

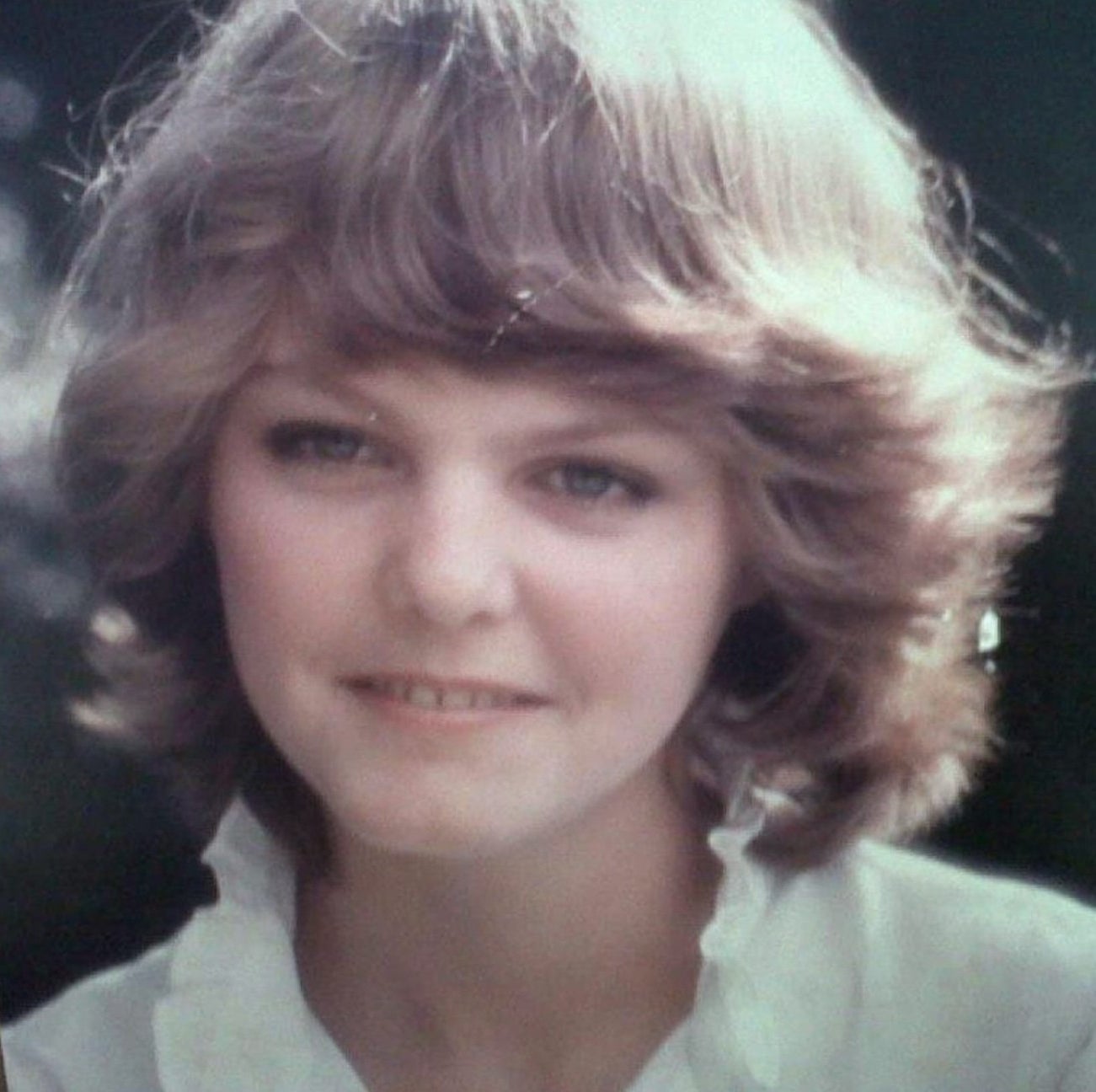

“My sister Kay was a connector,” he says. “She could see things from different people’s perspectives, so the foundation is really an empathy engine. We connect people who have resources with real individuals they can help. To be a Kay Mason scholar means you’re special, smart and unusual – as my sister was.”

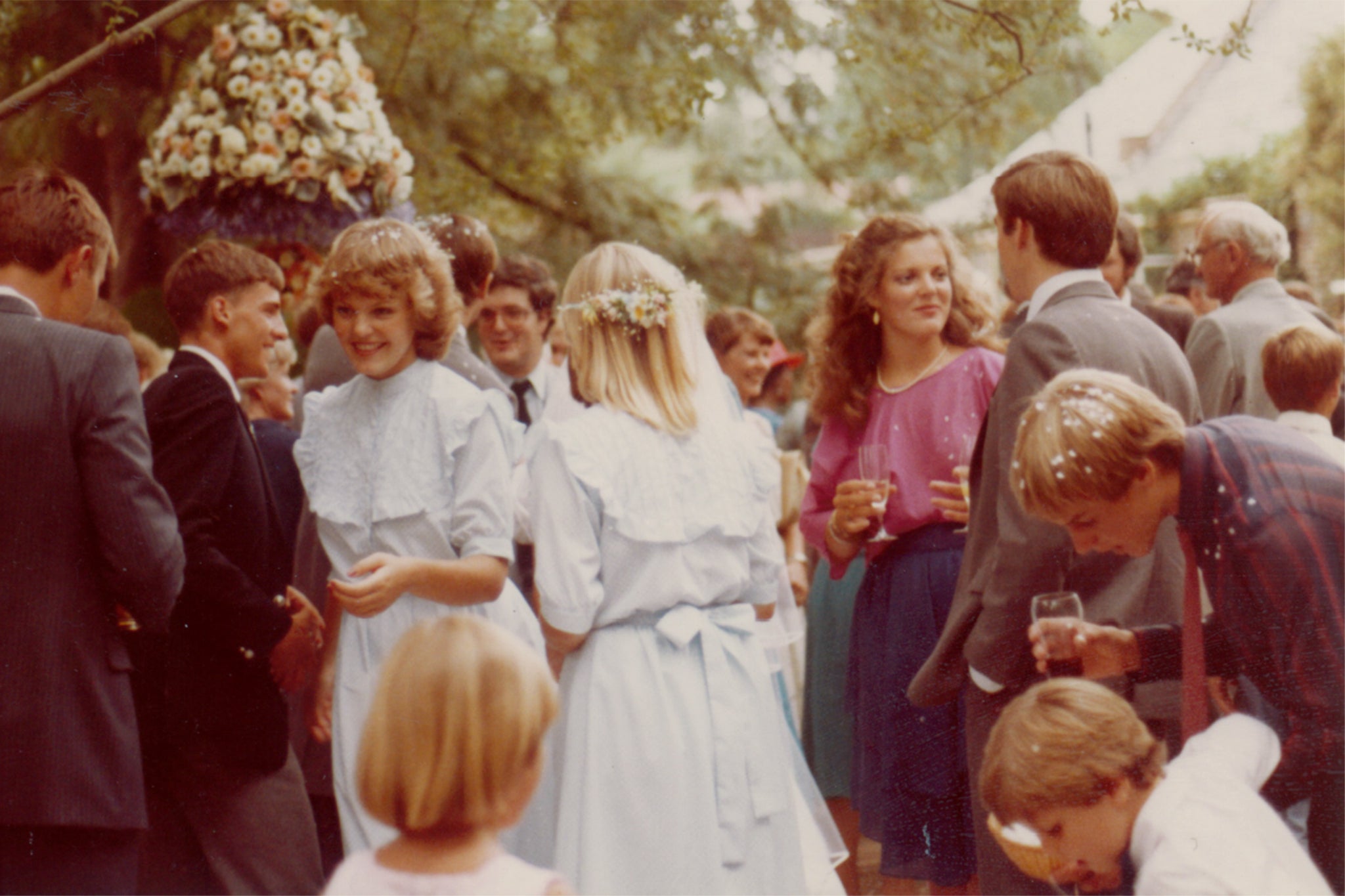

There were no signs in Kay’s childhood of the mental illness that would overshadow her early adulthood. Richard, Kay and their two siblings, William and Jenny, were all born and raised in South Africa by politically active parents.

“I think Kay found life quite easy,” says Mason. “She was beautiful, intelligent and had lots of friends. She was also incredibly lucky. You played backgammon with Kay, and she’d say, ‘I’m going to roll a double six’. And she would.”

But after leaving home to study computer science at university, Kay started experiencing mood disturbances sparked by a combination of being trailed by police because she was politically active, as well as overwork and too little sleep. In 1988, she took her own life.

“It’s such a tidal wave of grief that it becomes quite hard to connect with your emotions,” he says. “You know that if you let it overwhelm you, you won’t function. So you keep it in its own place. For a long time, I couldn’t cry at all. Or I’d laugh when I wanted to cry, which is also terrible.”

The experience however also concentrated his ambition to be a writer. With a new sense that time was limited and having moved to the UK with his parents, Mason decided to write 500 words of his first novel each day before school assembly and rewrote the book twice during a gap year. The Drowning People was published to great acclaim when he was studying at Oxford.

And it was from the book’s royalties that the Kay Mason Foundation was born.

Creating change was part of his family story. Mason’s Afrikaans mother Jane worked for politician and renowned activist Helen Suzman and was herself vocal in her opposition to apartheid. Mason remembers her setting up a racially mixed – and very illegal – nursery in their back garden when he was young, to enable black women working in white neighbourhoods to leave their children somewhere safe during the Soweto riots. He also remembers his mother chasing off the police who came to shut it down.

“The injustice of apartheid was very clear to me as a little boy and I’d had a good education which gave me opportunities and the ability to take risks,” he says. “I wanted to help other people have those chances.”

But writing his second book was complicated. The commercial aspirations of publishers who wanted to repeat a global hit collided with his newfound commitment to the children the foundation was funding. Four had been put through school when it started in 1999 and four years later, Mason had committed to funding 30 students through his sister’s foundation.

“The thing about having responsibility for children is that you can’t know what it’s like until you’ve got it and there’s no plan B. My most commercial publishers said the book I’d written was too complicated and asked me to rewrite it.

“If the kids weren’t involved, I’d have just said no. But a lot was riding on it, so I tried to rewrite the book into a thriller. It was like taking a very blunt knife and pushing it slowly into my own chest. I just couldn’t take it.”

Aged 25, Mason also experienced a crippling suicidal depression. Desperate to keep the charity going, he asked readers to donate. They responded, and he was able to return to the original idea for his second novel. He also saw a psychiatrist for the first time.

“I felt suicidal, but he gave me some vital advice. He said the important thing is not to avoid going down, it’s to avoid going up. Maintain a steady mood state. A six and a half, or seven, out of 10. He was right.

“I learnt that the feeling of being suicidal will pass. Suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem and has so many consequences for the people around you. But there are ways to get through what you’re feeling and to find happiness again.”

Both Kay’s and Richard’s mood disturbances, however, were not simply chance events. They came from a genetic line that was one part adventure and rebellion, the other a genetic predisposition to a particular, and severe, kind of mental illness. Their great uncle and mother’s cousin had taken their lives and other relatives had also suffered extreme highs and lows.

A combination of medication and healthy habits such as daily meditation, getting enough sleep and plenty of exercise, allowed Mason to stabilise his mood and develop his career as a novelist. He says he now prefers writing for TV because it takes him out of the long periods of isolation that novel writing requires.

“I’m an introvert brought up to behave like an extrovert, but I do like being around people,” he says.

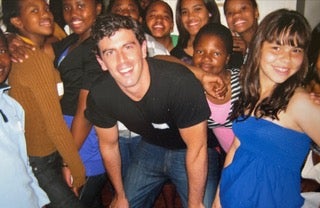

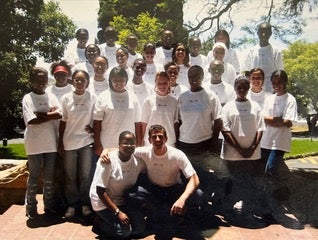

Twenty-five years on, the Kay Mason Foundation has funded 500 of South Africa’s brightest children and created some extraordinary trajectories.

Siyamthemba Mrawli had grown up in a gangland and had been stabbed several times when Mason met him. After a KMF scholarship, he got a business degree from the University of Lancashire. Now, his first start-up Blankspace Technologies has just been given a multimillion-dollar valuation.

Patricia Hector was born on the streets, grew up in an orphanage and is now a corporate attorney for a major bank. She’s also training to be a pilot and has set up an NGO to help girls in the orphanage where she spent her childhood.

Siphosethu Pama was a 12-year-old cleaning toilets when Mason first met her: she is now a senior account manager at Publicis, as well as the chair of the Kay Mason Foundation global board.

“We need ethical leaders who know what it is to be poor,” says Mason. “And our model works because we don’t fund thousands of kids but our alumni become leaders across society, and can bring about real change.”

Today, the KMF supports children from secondary school into the first years of their careers through financial aid, nurture, and access to a network of 350 global mentors.

Mason continues to write, and while death and grief were repeated themes in his fiction for a long time, he now writes more about “pleasure, sex and the challenges of loving people”. His recent novel, History of a Pleasure Seeker, was described by The Washington Post as “the best work of fiction … in many moons” and was an Oprah pick.

He admits, however, that Kay’s suicide has left an indelible mark on his family.

“There are a lot of individually close relationships in my family and a lot that’s really wonderful in it,” says Mason. “But Kay’s death broke something in our family connection that we haven’t really recovered from.”

The foundation in Kay’s name, however, has also reclaimed vital hope.

“Working for the KMF over 26 years has accessed something very profound in me,” says Mason. “For many years, the words ‘Kay Mason’ only signified loss. But now that has changed. All these amazing people have come into my life as a result of having lost my sister and some of that tragedy and trauma has been transformed into a profound joy. I know that is what she would have wanted.”

The Kay Mason Foundation auction will be held at 7pm on 20 March. To view lots online and make silent bids, or submit a pre-bid for the live auction, click here. You can find more information about the Kay Mason Foundation here

If you are experiencing feelings of distress, or are struggling to cope, you can speak to the Samaritans, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch.

If you are based in the USA, and you or someone you know needs mental health assistance right now, call or text 988, or visit 988lifeline.org to access online chat from the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. This is a free, confidential crisis hotline that is available to everyone 24 hours a day, seven days a week. If you are in another country, you can go to befrienders.org to find a helpline near you

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments