Books of the month: From Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun to Melissa Broder’s Milk Fed

Martin Chilton reviews six of March’s biggest releases for our monthly column

“I find Marcel Proust crushingly dull,” admitted Kazuo Ishiguro in 2015. He presumably won’t be rushing to read The Mysterious Correspondent (Oneworld) then, which contains nine of the Frenchman’s unpublished short stories, and is released to mark the 150th anniversary of the author’s birth. In truth, the collection is probably one for true Proust devotees only, as it is too fragmented to work as a stand-alone set of short stories. Ishiguro’s new novel Klara and the Sun (reviewed in full below) is, in contrast, a dazzling delight.

March is another month of strong fiction, from Edward St Aubyn’s Double Blind (Harvill Secker), about a transformative year for three friends, to Alan Warner’s Kitchenly 434 (White Rabbit), a delightfully comic tale set in an English country house in the late 1970s. I also enjoyed Tariq Smith’s droll debut novel Whiteout Conditions (Dead Ink Books), about a young man strangely drawn to funerals. In the short-story collection Land of Big Numbers (Scribner), Te-Ping Chen, the former Beijing correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, offers a wry, tender look at modern China. I particularly liked “Shanghai Murmur”, the story of a young woman’s struggle to make it in a city exploding with wealth.

There are some first-rate releases from big-hitting crime writers this month, including Harlan Coben’s Win (Century), a pacy thriller about a kidnap case that has baffled the FBI for decades; TM Logan’s Trust Me (Zaffre) about a stranger handed a baby, along with a warning note, by its fleeing mother; and Peter May’s gripping The Night Gate (Riverrun), which is set in France, both in the war-torn 1940s and in contemporary pandemic times.

If you’re finding it hard to engage with fiction at the moment, I can recommend a host of terrific non-fiction books out this month. In her small, potent polemic, The Soul of a Woman (Bloomsbury Circus), author Isabel Allende writes about the toxic effects of “machismo”, combining wit with anger as she picks apart the patriarchy. Allende argues that violence against women “is the greatest crisis that faces humanity”. This chimes with one of March’s most important books, Jane Monckton-Smith’s In Control: Dangerous Relationships and How They End in Murder (Bloomsbury), which explores domestic violence and the coercive control of women. Monckton-Smith, a professor of forensic criminology who trains police forces on assessing threat, examines more than 400 cases of “intimate partner homicide” – a crime that has doubled in the UK during the pandemic – and her powerful book offers a strategy for intervention that would save lives.

Chris Woodford’s Breathless: Why Air Pollution Matters – and How It Affects You (Icon Books) is full of scary information, especially the chapter “Killing Us Softly”. Bad air lowers life expectancy around the world and the insidious effects start early. “If you’re a 12-year-old growing up in London, dirty air (largely from traffic) is making it significantly more likely that you’ll suffer from depression by the time you hit 18,” Woodford states.

There’s plenty of interesting strangeness in Seamus O’Mahony’s The Ministry of Bodies: Life and Death in a Modern Hospital (Apollo) and his anecdotes about life in the NHS. In one section, the doctor looks at the epidemic of chronic liver disease – and he includes a rare slice of cheery news for the bald community. “I have often been struck by the sheer hairiness of men with liver cirrhosis: you hardly ever see a bald one,” reports O’Mahony.

How to Read Numbers: A Guide to Statistics in the News (and Knowing When to Trust Them) by Tom Chivers and David Chivers (W&N) is an erudite, enlightening guide to the numbers we read in the news – and why they are so often wrong. The authors make sense of dense material and offer engrossing insights into sampling bias, statistical significance and the dangers of believing the casual language used in newspapers.

Evert Sprinchorn’s scholarly biography of Henrik Ibsen, Ibsen’s Kingdom: The Man and His Works (Yale University Press), includes an interesting section on how the Norwegian playwright employed syphilis as the central metaphor in his play Ghosts. Venereal disease was rampant in Scandinavia in the 1880s and Sprinchorn charts how the author of Doll’s House was always willing to tackle a taboo subject.

One of the best memoirs of the month is There and Black Again: The Autobiography of Don Letts (Omnibus Press, written with Mal Peachey), which tells the action-packed story of a filmmaker, musician, and DJ who turned so many people on to reggae. There are great tales of befriending Bob Marley, being part of a tour with The Clash, and Letts’s involvement in the boom of MTV.

Finally, folk singer Sam Lee’s gorgeously illustrated The Nightingale (Century) is a marvellous miscellany of the nightingale, the sweet-singing bird which is now, alas, one of the “endlings” – the last of a species facing extinction.

Non-fiction from Craig Taylor and Bruce Greyson, along with novels by Emma Stonex, Lisa Harding, Melissa Broder, and Ishiguro are reviewed in full below.

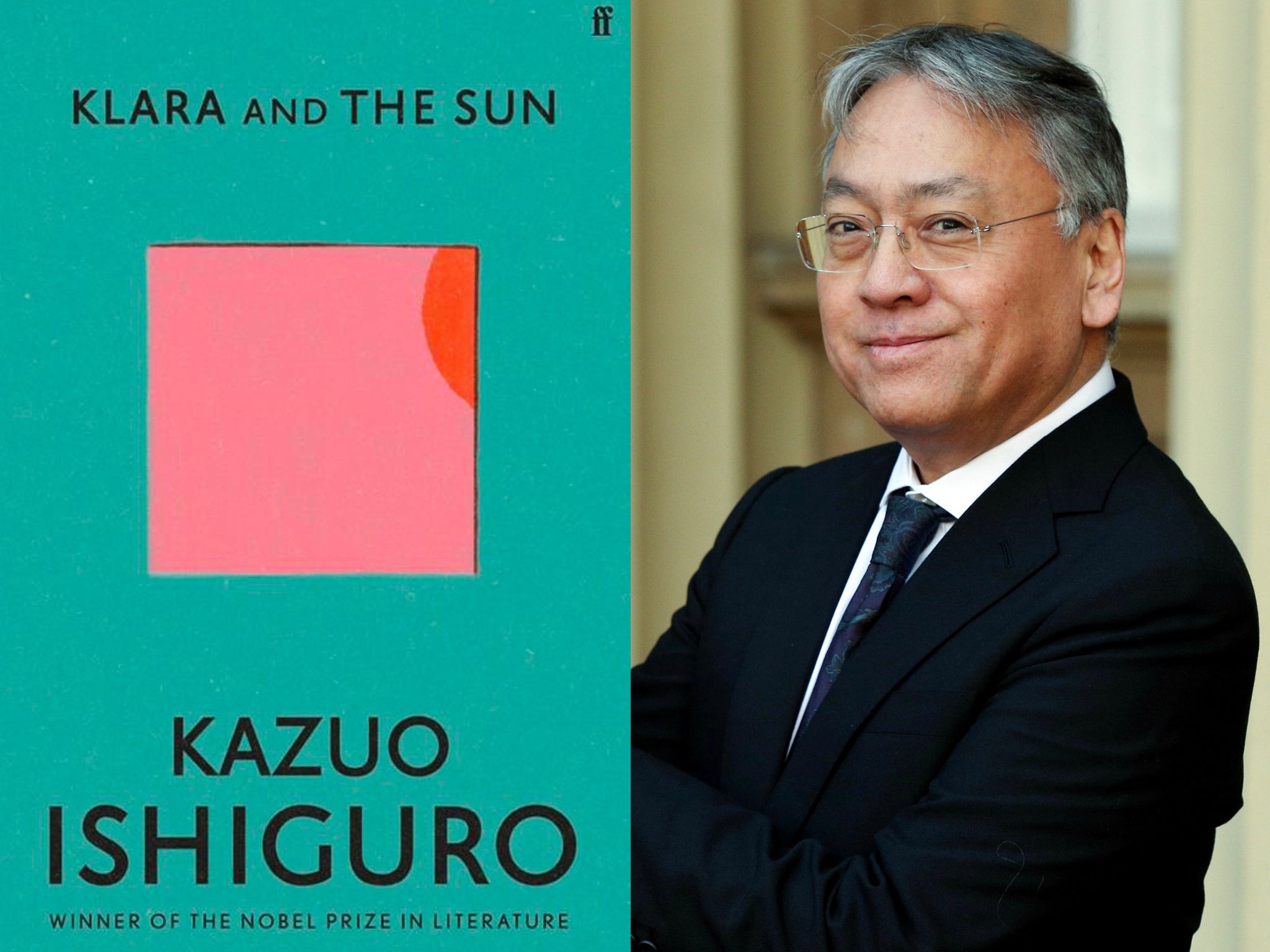

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro ★★★★★

Klara and the Sun is Ishiguro’s eighth novel and his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize in Literature. Early on in the novel, Klara, an Artificial Friend with remarkable observational skills, stands in the shop window of the AF store and tries to make sense of human behaviour. “I became puzzled, then increasingly fascinated by the more mysterious emotions passers-by would display in front of us,” she remarks. As with most things Ishiguro, the deceptively simple prose is the prelude to a volcanic eruption of ideas and observations.

The novel, a haunting dystopian fable-like story set in an unspecified future America, is about the relationship between a solar-powered robot and its teenage owner Josie. She is seemingly dying of an illness (what exactly is never explained), in an era in which gene-editing has become the norm and biotechnological advances have made the creation of “unique” human beings an achievable goal. “We are living in a time when the most powerful companies in the world are successful because they can map our behaviour, and our future behaviour. The assumption is that we have the means to excavate who people are,” recently said the Booker-winning author of The Remains of the Day. The modified children in the novel (the so-called “lifted kids”) seem a pretty cruel, soulless bunch, and Ishiguro depicts a world where the rich remain firmly in control.

There is real emotional intensity in the scenes between Josie and her mother (the novel is dedicated to the novelist’s mother, Shizuko, who was 92 when she died in 2019) and we see, in their troubled relationship, the prospect of a worrying future, where the very idea of individuality is at risk. Klara gradually begins to realise that she is being programmed to take Josie’s place – a plot device that allows Ishiguro to get to the heart of the complex, stirring questions he raises in the novel: for example, what happens to the idea of love when we remove the concept of an individual’s uniqueness?

Klara is a warm, empathetic character. She is desperate to figure out what motivates people (they are as hard to fathom for a robot as they are for a human) and she ponders on the “manoeuvres” they make in their desperate bid to escape loneliness. Some of the most touching scenes involve Klara and Josie looking out of her bedroom window at the fields, watching the setting sun. “The grass was tall in all three fields, and when the wind blew, it would move as if invisible passers-by were hurrying through it,” writes Ishiguro, who is a true master of making art out of everyday details.

The novel deals with grief (Josie’s sister Sal), young love (Josie’s friend Rick), and scientific ambition (the sinister Mr Capaldi), but above all Klara and the Sun is a tender novel of ideas. Although it is disturbing, it is also optimistic. There is brightness to be found in this future world: it is the sun that nourishes Klara; the sun that she believes is the source of everything good.

As we hurtle towards a future filled with AI technology, it is appropriate, and a neat irony, that in Ishiguro’s story it falls to Klara, an Artificial Friend already being made obsolete by a newer model, to offer a heartfelt defence of the uniqueness and the power of the human soul. Ishiguro paints an ominous picture, but he does seem to hold out for the lasting power of the “something very special” inside us, qualities that will remain beyond the reach of artificial intelligence.

‘Klara and the Sun’ by Kazuo Ishiguro is published by Faber, £20.

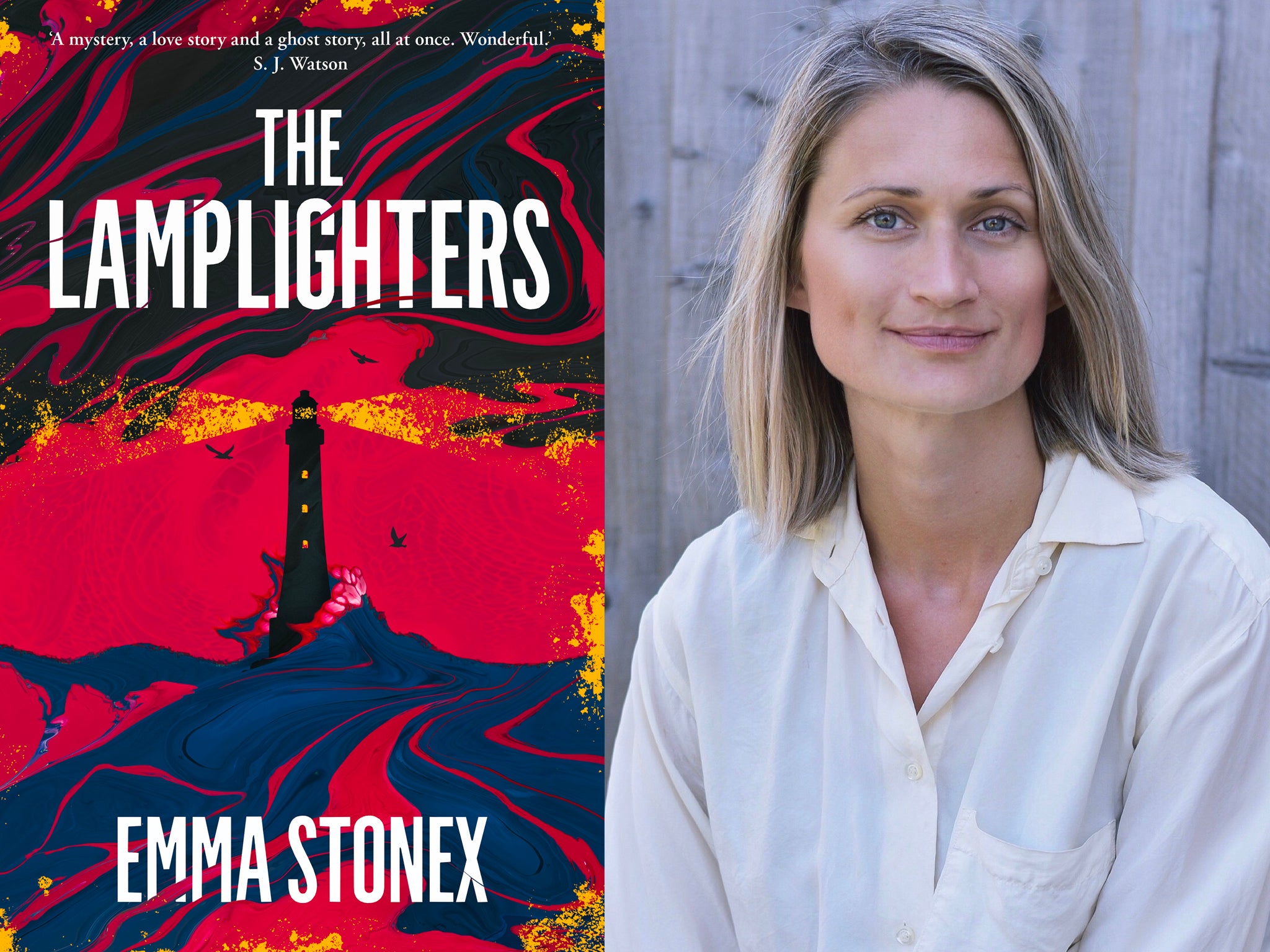

The Lamplighters by Emma Stonex ★★★★☆

“They’re an abnormal breed, lighthouse keepers,” says a character in The Lamplighters, an absorbing literary thriller about the strange fate that befell three doomed men on a Cornish lighthouse called the Maiden, in December 1972.

Emma Stonex has taken the bare bones of a real story – the enduring mystery of three keepers who disappeared without trace from Flannan Lighthouse on Eilean Mòr, Scotland in 1900 – as the foundation for her own riveting novel. The Lamplighters is mainly set in 1992 – with lots of flashbacks to the 1970s – when adventure novelist Dan Sharp tries to cut through the hearsay and piece together the truth behind the 20-year-old tragedy. Why was the door to the Maiden locked from the inside? Why were the two clocks inside both stopped at eight forty-five? Were the lighthouse owners Trident involved in a cover-up?

As he unravels what really happened to Arthur, Bill and Vincent, Stone interviews Helen, Jenny and Michelle, the loved ones left behind. Stonex’s clever slow reveal is as much keen psychological drama as it is an intriguing thriller. The Atlantic Ocean itself is an ominous character in the novel. Bill regards the sea as something that has “infected us all”, while Helen comments, “Sometimes I consider the sea to be like a great big tongue, licking up the people around me.”

The novel is also an interesting meditation on loneliness, for the women left ashore as much as for the men who are quarantined on a bleak building out at sea. There is a poignant moment when Arthur remarks that his wife Helen does not really put up festive decorations, because: “I’m rarely there for Christmas. There’s no point in her doing it alone.”

The Lamplighters is also a portrait of a vanished way of life (lighthouses are now all automated), and neatly captures the claustrophobia of being cooped up together. There are slights and festering animosities between Arthur, Bill and Vincent – although their dynamic lacks the grotesqueness (and flatulence) of William Dafoe and Robert Pattinson’s angry characters in Robert Eggers’s disturbing 2019 movie The Lighthouse.

One of the novel’s many qualities is that Stonex offers a satisfying conclusion to the mystery that is believable and suitably dark.

‘The Lamplighters’ by Emma Stonex is published by Picador, £14.99

Bright Burning Things by Lisa Harding ★★★★☆

The first 80 potent pages of Lisa Harding’s Bright Burning Things are an eviscerating account of the life of a drunken single mother called Sonya Moriarty. She admits she is “a sad, needy clown” and a “selfish, selfish lush”, and Harding does not spare her in a raw, penetrating portrait.

Sonya’s four-year-old son Tommy is the only stabilising influence in her life, yet she puts him in deep distress with her drunken, manic behaviour. When she remembers to feed him, it is with burned fish fingers, or marmalade sandwiches (his diet is very orange). She distrusts offers of help, branding her elderly neighbour Mrs O’Malley a “snoop” and warning Tommy that the old woman wants to keep him in her house and fatten him up like the witch does in Hansel and Gretel. Poor Tommy’s main emotional support is the love of a decrepit old dog called Herbie (one of the stars of the novel).

Harding’s incredibly moving novel is set firmly in Sonya’s Irish present, alluding occasionally to her past as an acclaimed star-in-the-making actress. Interestingly, Harding is a playwright and actress as well as a writer. One of the author’s deft decisions is to leave Sonya’s past in London as a ghostly backdrop. We see the loss and the damage only in small snapshots, for example when she recalls a glamorous film director lover and his gift of a vintage Spider car. What makes Sonya interesting is that hers is constantly a mind “at war with itself”. One moment she is admitting she misses the excitement and attention of the West End, the next she is dismissing the “stupid, fawning” fans who followed her career.

No spoilers, but things come to a head when Sonya, suffering repeated blackouts, is forced into rehab. The final 300 pages of Bright Burning Things are an achingly honest exploration of a person on the edge, fighting for her own survival. In this battle, Harding also explores the men in Sonya’s life: from the tense, fraught relationship with her father, to the creepy controlling counsellor who somehow plants himself in the middle of her life.

Bright Burning Things is a painful, emotional read, but there is hope amid the despair. “Tomorrow – there’s always tomorrow,” Sonya says.

‘Bright Burning Things’ by Lisa Harding is published by Bloomsbury, £14.99

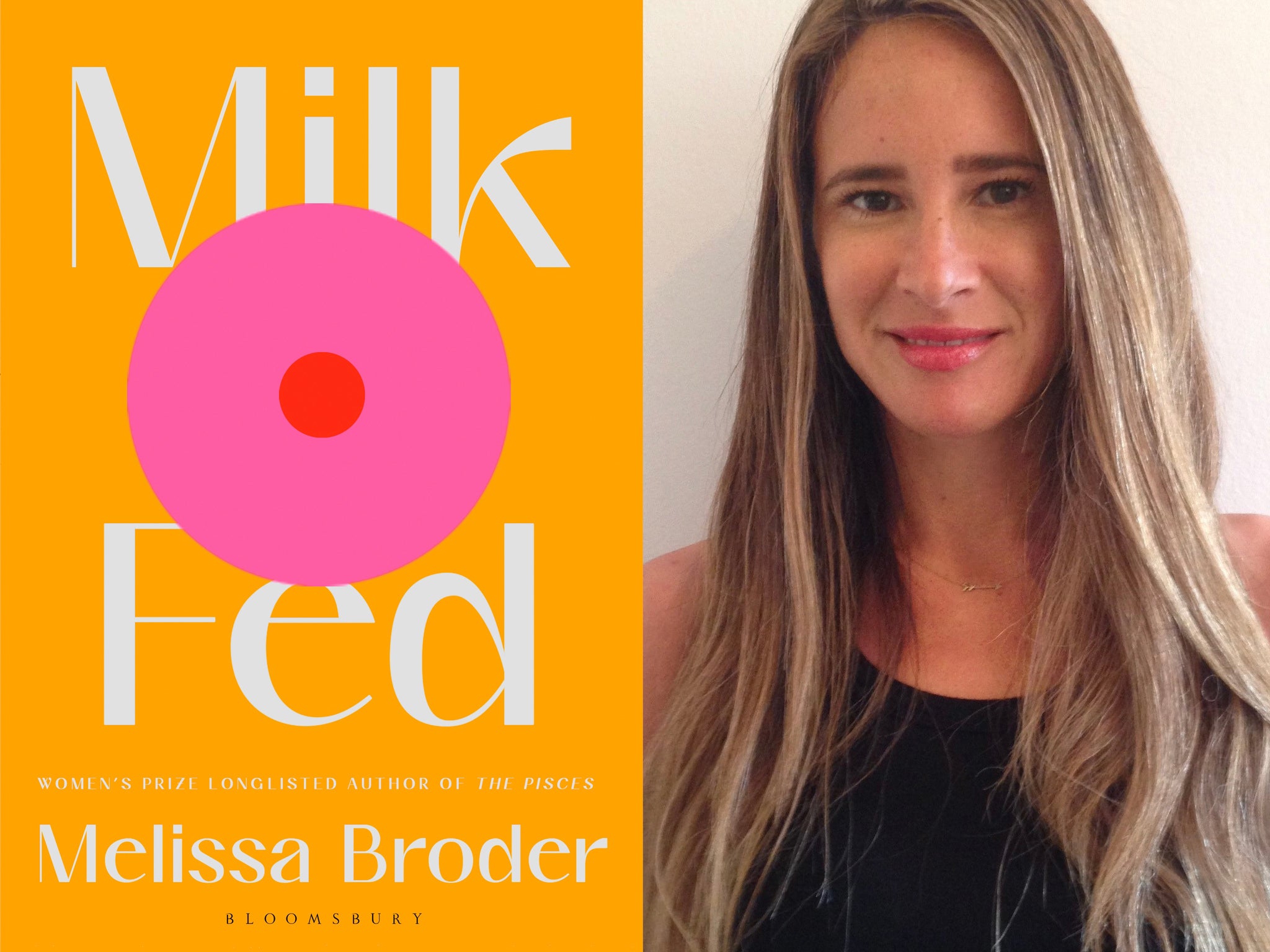

Milk Fed by Melissa Broder ★★★★☆

There is an amusing scene in Milk Fed in which former anorexic Rachel Meredith is trying to sneakily eat a protein bar in a toilet at the same time as the woman in the adjacent stall is having a bout of diarrhoea. Melissa Broder’s edgy, honest novel explores the messy and all-too-human mixing bowl of love and desire, through the story of two vivacious young Jewish women.

Rachel is candid about her own chaotic relationship with food – and the power it has exerted on her life. Now obsessively lean, she carries the mental baggage from her days with an eating disorder, when she weighed herself 10 times a day and judged herself to be “disgusting”. She recalls how her mother “persuaded me to stay thin by insulting me”.

Her years of staying slim end when the 24-year-old former anorexic from Los Angeles suddenly develops a crush on a ‘Zaftig’ called Miriam Schwebel – a Yoghurt shop worker who was “undeniably, irrefutably fat”, a woman who “exceeded my worst fears for my own body”, Rachel admits. Rachel falls off the diet wagon with a mighty crash.

Broder delicately builds up their highly erotic love affair, a relationship in which the sexual charge of eating is made very clear. There is a lot of sex in Milk Fed, graphic, steamy sex, presented with humour and tenderness. In one offbeat moment, as Rachel watches the movie Charade, she ruminates on the idea of “fucking Audrey Hepburn”, comparing her “tiny titties” unfavourably with the buxom Miriam.

As well as exploring sexuality, desire and society’s strictures about body image, Milk Fed also portrays the shallow, phony landscape of modern LA media-land. “I could never tell if other people genuinely believed their own bullshit or not,” Rachel remarks.

Both women have powerful mothers and Broder explores the damaging effects of family emotions, as their affair grows ever more passionate. Tensions over religion (Rachel is lapsed, Miriam is Orthodox) start to erupt. Rachel’s background, and the memories of feeling forsaken, have left her with a terror of being rejected. Milk Fed tells us that the past is difficult to shake.

Although Milk Fed is a humorous, deliciously rich novel about sexual desire, it is also an unsettling look at spiritual hunger. Broder makes you think about the compensations people seek for the pain of loneliness. There are lots of memorable moments in this entertaining novel – and it will be hard to look at a burrito again without thinking of Rachel’s confession that she wants to “hold it to my cheek, or put it over my shoulder and soothe it”.

‘Milk Fed’ by Melissa Broder is published by Bloomsbury Circus, £16.99

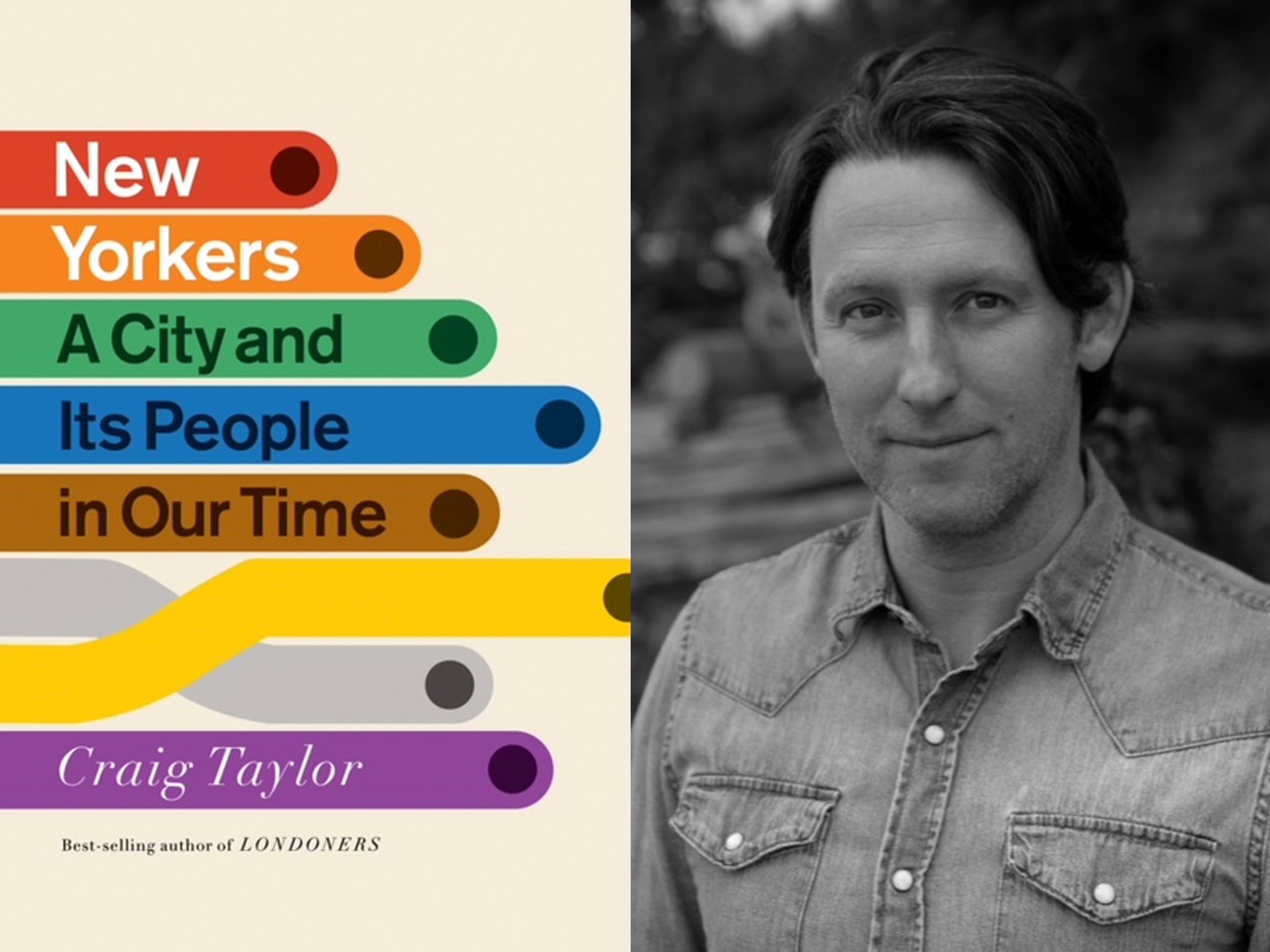

New Yorkers: A City and Its People in Our Time by Craig Taylor ★★★★★

Craig Taylor’s 2011 oral history of London was a series of superb snapshots of England’s capital. He returns to this format for New Yorkers: A City and Its People in Our Time, another enlightening tapestry of one of the world’s liveliest cities. Over six years, Taylor gathered 400 hours of tape, from conversations with more than 180 New Yorkers, to tell the story of America’s most glamorous city.

If there is, as Billy Joel would have us believe, a “New York state of mind”, then it’s certainly one of homespun philosophy; but the real skill of Taylor is to get beyond the clichés (however grounded in reality) and take us to the heart of a place of bravado, non-stop hustle and “stimulus overload”.

Former cab driver Zack Arkin tells the author that “in New York, people are the textures” and it is the richness of the accounts from people of all walks – the interviewees range from a personal injury lawyer to a lice consultant – that makes the book so fascinating. “Trust me, the city is involved in almost every session I have,” confides a therapist.

Some entries are jaw-dropping, opening up a world most of us never get to see. Elevator repairman David Frye’s account of digging out a lift shaft is excruciatingly vivid. It’s no wonder he divides New York into “those people who piss in their elevators and those who don’t”. Being a subway conductor isn’t much better. “At the end of the day you blow your nose, everything’s black,” says Sal Leone.

New Yorkers have been through the mill in modern times, including facing the perils of the AIDS tragedy, the Manhattan Blackout, Hurricane Sandy, 9/11, the recession, and now the Covid-19 crisis. Student Nora Bauso recalls that after the hurricane, the family photos of strangers, carried out of houses by the currents, turned up in random places, including staring up at you from bushes, for the following year.

The tragedy of 9/11 still looms large. One New York dentist talks about the many health issues that came in the wake of the terrorist attack. “In New York, you get a lot of grinding. You get cracked teeth, TMJ issues, joint issues,” reveals Arthur Kent. “If you experienced 9/11, you’re married to it and there’s no divorcing it,” says Pete Meehan, a policeman who suffers from neurological conditions after being “contaminated” by the poisonous dust that followed the collapse of the Twin Towers.

Taylor’s book includes some sections about coronavirus. A patient called Don Bauso captures the sheer confusion and seat-of-the-pants tension of trying to survive in a hospital that was engulfed in “fucking mayhem”. Even veteran nurses were traumatised.

“It’s going to affect all the nurses I work with for the rest of their lives. The amount of dead people they’ve seen, the amount of bodies they’ve had to wrap, the amount of people dying alone,” says Siobhan Murphy, a nurse at Long Island Jewish Hospital. Her story is compelling – and horrifying. There is a heart-wrenching revelation: when patients in one hospital were nursed back from the brink of death, their release was marked by playing the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun” over the intercom system.

Gladys DeJesus Mitchell, a retired police dispatcher, says that she is still “affected physically, emotionally and psychologically affected” by her experiences of working through 9/11. “I have five illnesses associated with September 11th. I want people to know that everything that people are going through with Covid – that’s going to last them a lifetime.”

It’s not all bleak, however, and many accounts of the zany, fun side of New York are enthralling – and reading the book during lockdown makes you yearn for the sheer human connectedness described in its pages.

Start spreading the news: Taylor’s book is a stunning work of modern social history.

‘New Yorkers: A City and Its People in Our Time’ by Craig Taylor is published by John Murray on 8 March, £25

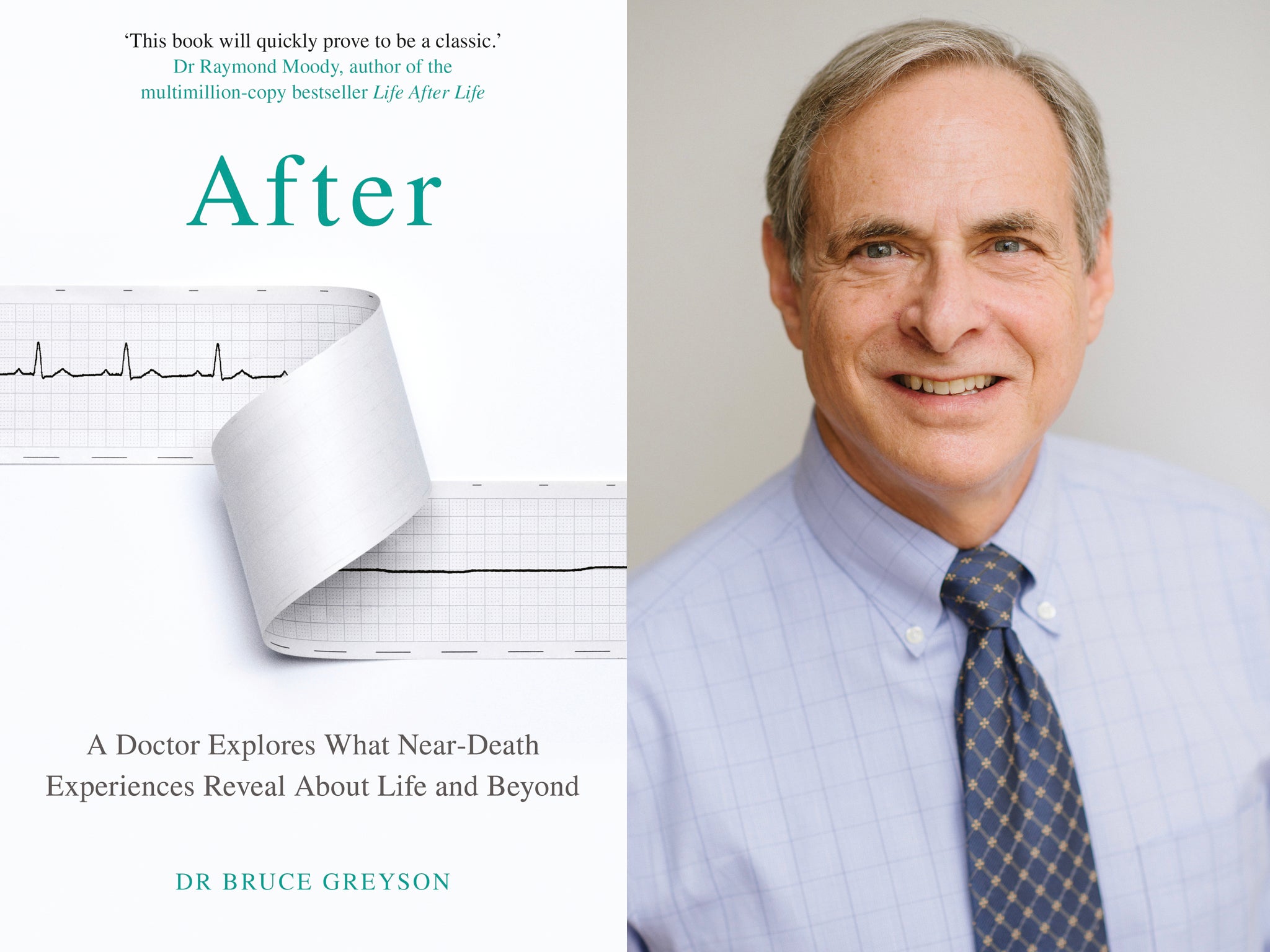

After: A Doctor Explores What Near-Death Experiences Reveal about Life and Beyond by Bruce Greyson, MD ★★★☆☆

If you are looking for a book that will challenge your understanding of how the world works, and which raises unsettling questions about life and death, then Dr Bruce Greyson’s study After: A Doctor Explores What Near-Death Experiences Reveal about Life and Beyond (Bantam Press), is full of strange anecdotes and observations that explore the nature of consciousness.

Greyson, a professor of psychiatry and neuro-behavioural sciences, describes himself as a man “trained to be sceptical”. He is pleasingly candid about finding some things “very difficult – if not impossible – to explain”, including the number of people who have a near-death experience (NDE) vision encounter with a dead person they could not have known to be deceased. It is bafflingly common that a survivor’s NDE account is soon followed by confirmation that the relative they met had in fact been recently killed, without any chance that the person experiencing that NDE could have known this. After is a book that forces you to consider the unknown and try to come to terms with the unexplained.

It is a recurring pattern for people having NDE’s to see their past being replayed in a “total life review”. As people hover between life and death, a great number say they had to face the consequences of their actions in a moment of reckoning. One man, who had a NDE after being crushed by a truck said that for him the “life review” raised a question we should all consider at life’s end: “Will you be totally devastated by the crap you’ve brought into other people’s lives?”

‘After: A Doctor Explores What Near-Death Experiences Reveal about Life and Beyond’ by Bruce Greyson, MD is published by Bantam Press on 11 March, £16.99.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments