She was America’s parenting hero. Then the backlash came

Emily Oster set out to empower moms through data. Now she has angered everyone from gentle parenting advocates to the medical establishment — but she doesn’t mind at all, she tells Holly Baxter

It’s lunchtime and Emily Oster has been reading about tapeworms all morning. “There’s 848 kinds of parasites, in case you’re wondering,” she tells me, with a slightly unsettling smile on her face. “The worms can grow to be 12 meters long.”

Luckily, I have a toddler, so I’m not easily grossed out. I meet Oster at her brightly lit, minimalist office at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, with a dog-eared copy of her first bestselling book — Expecting Better — in my bag and a sticky puddle of my two-year-old’s regurgitated blueberry breakfast smeared across my jacket sleeve. Like most people who had a child in the 2020s, I was gifted Expecting Better at my baby shower, and I promptly bought myself the follow-ups: Cribsheet (2019), The Family Firm (2021) and The Unexpected (2024). The books, which put Oster’s PhD in economics from Harvard to unconventional use, parse out the existing medical literature on a subject and let you know how seriously you should take the conventional wisdom on pregnancy and childrearing.

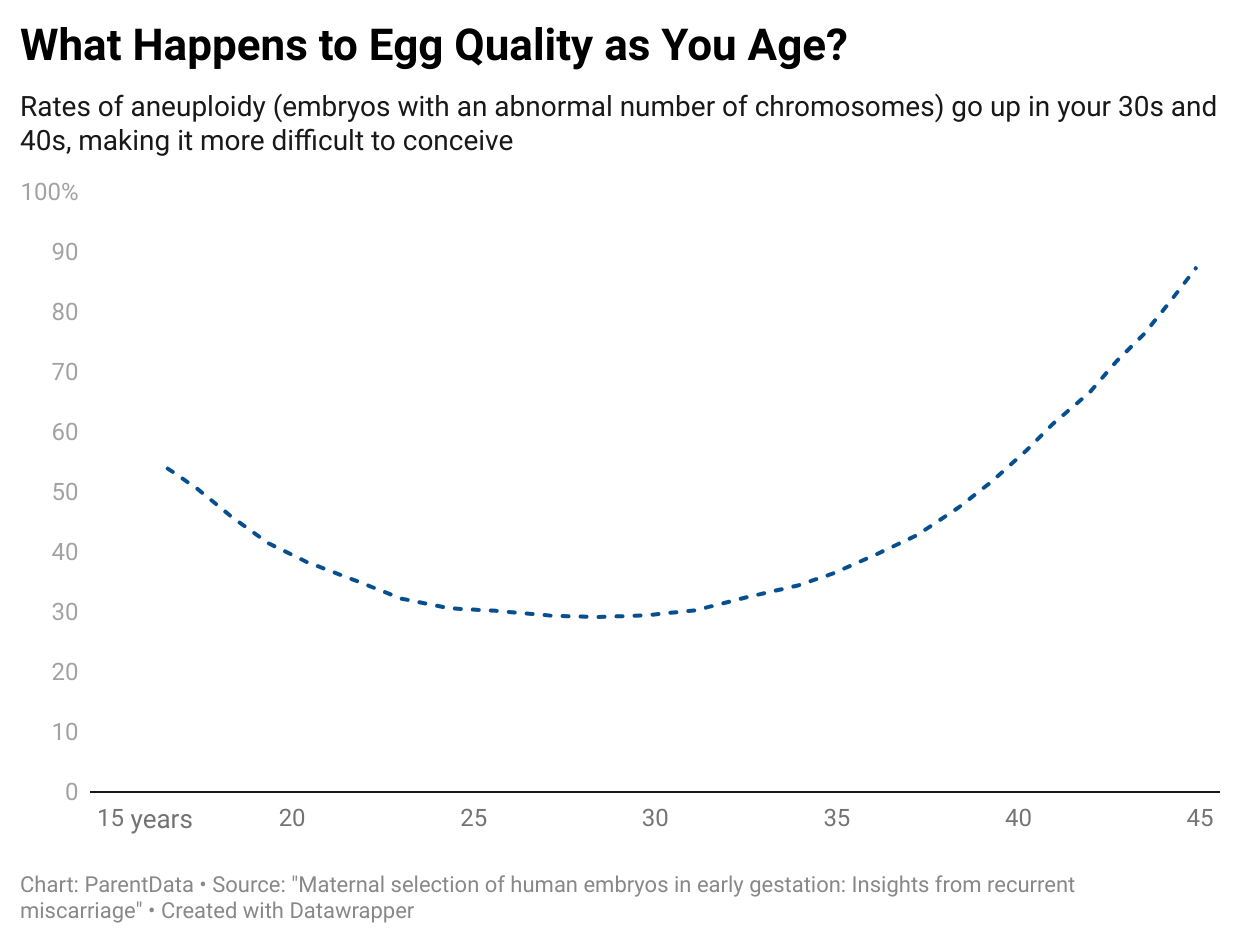

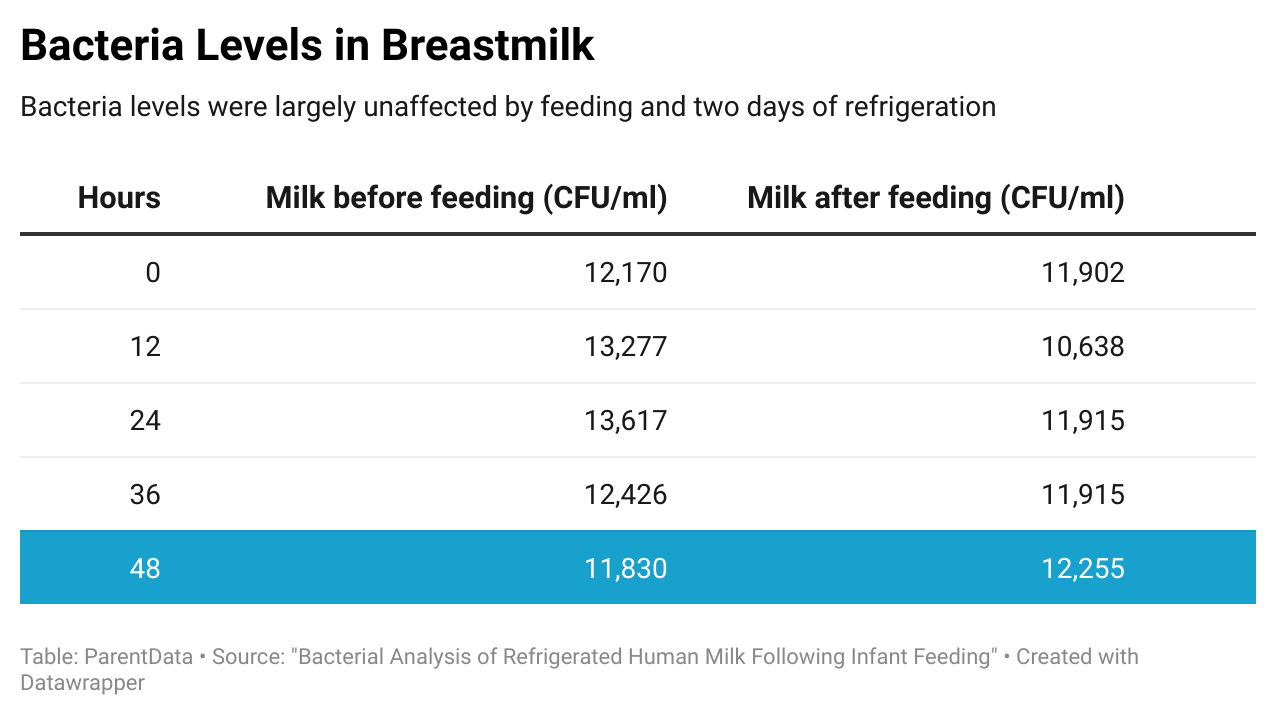

For women used to vibes-based parenting manuals and paternalistic medical attitudes, these books were nothing short of a revelation. Obstetricians will tell you to cut out coffee and alcohol; Oster concludes that studies suggest you can actually safely have a small amount of both. Doctors also caution women to avoid deli meats and never to eat sushi; Oster’s research suggests high-quality sushi is just fine (“People eat it every day in Japan,” she reminds me) and deli meats are no riskier than salads, but it’s best to avoid turkey. When it comes to breastfeeding, she concludes there’s only a minuscule benefit as compared to formula-feeding, and even that’s not entirely certain. She also says bacteria levels show you can probably leave pumped breastmilk in storage much longer than you’ll be told by your pediatrician.

The way she comes to these conclusions is by crunching numbers and then parsing out the quality of each medical study — were the people involved from a certain socioeconomic background or from an unusually risky or risk-averse group? Are listeria outbreaks really found primarily in sliced ham? She also looks into cause and effect — for instance, just because people who miscarry often report having consumed a lot of coffee, can we fairly conclude that that’s what harmed the pregnancy? (Answer: Probably not, because high levels of the pregnancy-protective hormone hCG causes nausea, and people who are nauseous tend to avoid caffeine. In other words, people whose pregnancies had the best chance of success might have been the ones who stopped drinking coffee in the first place.)

Expecting Better clearly isn’t just supposed to mean that you can be a better-informed expecting person. It’s also supposed to mean that pregnant women should expect better from the people who advise them. And that’s a message that resonated with a lot of people: her books have sold over a million copies internationally to date; her Instagram has just under half a million followers; and her Substack was the 10th most popular newsletter in the world by the time it moved off the platform in 2024, making Oster an estimated minimum of $600,000 annually. Due to its phenomenal success, Oster transferred the newsletter onto her own website, and ParentData is now run by a team of people who help her edit, publish and design each page as she reacts in real-time to parenting issues linked to the news.

This popularity has not come without controversy. Both the National Organization for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have criticized her stance on light drinking during pregnancy in press releases and public statements. The American Academy of Pediatricians released a statement underlining that they believe there is no safe level of alcohol consumption during pregnancy after her books began to gain traction. Oster refused to back down, retorting that she honestly reviewed all the available evidence and that women deserve to make informed decisions while pregnant. When a new literature review was done in 2020 in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine that led the author, Jack James of Reykjavik University, to suggest women shouldn’t consume any caffeine at all, Oster replied that the studies included in the review were too flawed for that conclusion: “You can say every study shows the same thing. Well, all of them have the same problem.”

A quote from James after the publication of his caffeine study neatly underlines how Oster’s attitude diverges from the attitude of the medical establishment: "Certainly, there is no evidence to suggest that caffeine benefits either mother or baby. Therefore, even if the evidence were merely suggestive, and in reality it is much stronger than that, the case for recommending caffeine be avoided during pregnancy is thoroughly compelling." That implication — that women should only be counseled to do things that directly benefit a pregnancy, and should be told to avoid anything that could be even potentially harmful — is what irks Oster.

“I have a couple of problems with that attitude,” says Oster. “One, I think it's not respectful. I mean, my general sense is that… women are adults, pregnant women are also adults, and we should tell people actual evidence so they can make choices for themselves. That's a core belief. But I also think even from an efficacy standpoint, I am not sure that this approach is actually delivering the thing you want. In part because if you tell people a thousand rules and you express them as if all of them are equally important, and people are just like: ‘Well, I can't do all of them. Like, I can't do all of those things,’ or like, ‘Well, I guess probably doing half of them is fine. I'll just sort of pick whatever half I think I would like,’ then you're actually not in a good position. Because you haven't helped people prioritize.” A person who gets told a fully abstinent approach to cigarettes and alcohol is equally important might reason they can only achieve one, so they’ll smoke lightly throughout their pregnancy, for example. And we know that the babies of people who smoked in pregnancy have much worse outcomes than the babies of mothers who had a glass of wine a week.

What’s even worse, Oster adds, is that sometimes people will look into the data themselves and realize their doctors are obscuring or overemphasizing the risks. And those people lose a huge amount of trust in the medical establishment. Later down the line, they’re the people who decide that doctors might also be lying about raw milk (not that big a risk, she concludes) or vaccines (a huge, population-level disaster). Then, before you know it, you have a measles outbreak, and the first death of a child from measles inside the U.S. in a decade.

Oster believes women both want and deserve accurate, up-to-date information about pregnancy and childrearing — Cribsheet and The Family Firm dive into the data surrounding such controversial parenting topics as sleep training, screen time, schooling, daycare and how to handle toddler tantrums — and she believes that delivering that information is a social good. In her office at Brown — a large, glass cube with white walls, strip lighting, two whiteboards and a few framed photographs of her colleagues’ kids — she juggles office hours with her economics students with research for the next ParentData article. A pile of cream-colored ParentData-branded sweatshirts spills out of a white Ikea shelving unit in the corner. Oster is wearing one of them, with her face bare of make-up and her dark hair pulled back. For some reason, I say, I expected her office to be a ramshackle, wood-paneled, slightly chaotic Ivy League stereotype.

“Oh,” she waves her hand, “I have another one, and it is more like that.” But it’s actually gotten too chaotic to meet in, she adds, mainly because there are piles and piles of shoeboxes in the center of it — she estimates there are seven pairs of New Balance alone. That’s because Oster has reached the level of celebrity where brands pay attention to her likes and dislikes, and send freebies in line with them. Running is a personal hobby — marathon-running in particular — hence the uncontrollable deluge of sneakers.

Yet Oster’s fame is a very particular type: for one section of the population, she’s a regular topic round the dinner table, and for the other, she’s basically invisible. When I mentioned on social media that I was en route to Providence to interview her, the DMs from my friends with kids were admiring: “Woah, parenting flex!” wrote one. Another, less admiring parent said I should ask Oster “why she’s so keen for pregnant women to drink.”

Spiky interactions are just part of day-to-day business for the 45-year-old mother of two, who seems almost pathologically committed to poking her head above the parapet. Deep in the middle of Covid lockdowns, she wrote about how schools should reopen, to much furor. Thinkpieces were published about her “attack on public education,” pointing out that some of her work is funded by conservative organizations that have opposed teachers’ unions in the past. Business Insider called her followers a “cult.” Rolling Stone wrote about how epidemiologists had told her to “stay in her lane.” NPR’s White House correspondent joked that “we should make ‘Emily Oster is my CDC’ T-shirts or mugs” (something that did little to dispel the “cult” accusations). Slate cautioned that Oster’s weighing-in on the topic had made it necessary to state “individuals cannot stand in for a federal agency.”

Typically on-brand, Oster then asked people to help her build a real-time study into the spread of Covid in schools by submitting monthly data through her website. It was an endeavor that led to its own backlash. To believe her detractors, she was the false prophet of the pandemic, popping up with seductive, irresponsibly individualistic conclusions based on incomplete data at a time when people were crying out for a savior.

“I'll tell you the thing that bothers me the most, which is when people are just like: ‘You're not a doctor,’” she says. “... It’s the most irritating because, I mean, of course that's true. I have never said that I'm a medical doctor… and certainly there are like doctors that I write with where they'll be like, you know, look, I don't agree with your take on this because I see what you're saying about studies, but the way that I'm seeing it in clinic is different. And that's a different approach. That's something that one could have like a concrete discussion about. But I think to just say, ‘Because you are not a doctor, you therefore are not in a position to comment on this data’ feels frustrating because I am an expert in a particular thing — in data.”

Yet even in the data world, she’s seen negative consequences to her work. When she was a young professor at the University of Chicago, pregnant with her first child, she sent a book proposal out for Expecting Better that was accepted. The rest, as they say, is history. Except it wasn’t exactly how Oster had imagined history might play out. Safely on tenure track at Chicago, the upcoming decision about whether she could stay was considered by most a check-box exercise. And then, following the publication of the book, her tenure was unexpectedly denied. Writing a book about pregnancy was considered “a weird thing to do,” she told The Skimm — weird enough that a male economist she worked with sat her down and asked: “I just want to understand, why would you do something like this?” It seemed like she might have made a huge “professional mistake.”

The aptly named Providence was where she ended up, juggling office time with economics students about population spread and statistical analysis with her own, endlessly burgeoning extra workload on crunching the numbers on parenting. A small city of cobblestone streets and coffee shops in New England — population 190,000 — Providence is just down the road from where she grew up in leafy New Haven, Connecticut. Gaggles of students gather in the central square by the war memorials, waiting for fully electric buses; local hotels fly LGBT flags; and the cafe by the Amtrak has a sign outside that reads: “This cafe stands against fascism. United we resist!”

It feels like an unnatural environment for Oster, who is careful never to give advice, stays away from politics and avoids committing (at least publicly) to any ideology. When I ask her if she’s a feminist, it’s the first time she flounders in a conversation where she’s usually both quick off the mark and straight to the point: “I certainly would have described myself as a feminist. I mean, I think for my mother this was a thing that would've been very important to her, and was very important to her. And I think, you know, in that sense, yes…. I think a lot about the messaging that I'm sending to more junior women and sort of how do you make sure that that one is acting as a role model, which is a little different than — aggressive is not the word I'm looking for, but sort of like different to an outward feminism. But I don’t know. I’m not really sure what that word means.”

Despite her reservations about the word, one might say it is a supremely feminist act to restore real choice to women, who have been underserved in healthcare for generations. But the reason I ask the question initially isn’t because of her books. It’s because of one particular episode of Oster’s 2024 podcast, Raising Parents, which is titled “Are Boys Being Left Behind?” In it, Oster interviews a variety of people — teachers, parents, founder of the American Institute for Boys and Men Richard Reeves — about why boys are continuing to fall behind girls academically, meaning that school results and college classes are skewing more and more female. As the mother of a young son and a self-proclaimed feminist myself, I listened with interest. I freely admit that I felt a little conflicted.

“Whenever Richard and I have done stuff in front of a broader audience,” Oster says, “people have feelings… They have a hard time with that message.” It’s surely difficult for women’s activists in the U.S. — who are still actively fighting for gender equality in so many spheres, and indeed the rolling-back of some hard-won victories like abortion rights — to be told to sit for a moment and think about how one area might be weighted against males. It doesn’t win you friends to write a podcast episode about equity for boys in that environment.

But Oster isn’t out to win friends. Indeed, drawing attention to the numbers that other people are ignoring is kind of her bread and butter. That’s one reason why she produced her podcast with The Free Press, the right-leaning, anti-“woke” website co-founded by Bari Weiss after she left The New York Times and supposedly committed to giving every viewpoint a fair hearing. Oster is careful when I ask her why she teamed up with The Free Press, saying only that it was a “really good opportunity to make a really high-quality podcast about complicated questions where we talked to a lot of people across the political spectrum,” something that “is hard to get in the kinds of echo chambers that we often are in.”

“There are definitely things I don't agree with The Free Press does,” she adds. “And there are things that I do agree with and, you know, we sort of knew going into that we would have places we agreed and places we didn't agree. And I'm really proud of what we produced.”

Not everyone featured on that podcast has been as easy to collaborate with as Richard Reeves. Oster says two people come to mind when she thinks of tough conversations she’s had in her line of work — one is Hal Chaffee, a self-styled public preacher who made a YouTube video called “How To Spank Your Kids the Right Way” and was interviewed for one of her podcast episodes about discipline.

“On the one hand, he was in some ways a perfectly pleasant guy to listen to,” says Oster, “and he was saying very things that sounded very sensible — and then he was like: You just have to make sure that you hit them hard enough. And I was just like: Wow, this is not aligned with how I [parent].” Why platform him at all, then? “Well, you know, this is not a fringe position in the U.S. Half of people are using some form [of physical chastisement],” she says. And if the data says it’s happening in those numbers, what’s the point of denying that person a seat at the table?

The other person she found difficult to deal with was Erica Komisar, a social worker and psychoanalyst who advocates hard for mothers to stay at home with their children and believes that daycare is harmful. “Oh man,” Oster smiles ruefully. “She was just a very judgmental person, who was very judgmental about my personal choices, who was very difficult to interview. It doesn’t happen to me that much, actually, where people are saying to your face: ‘You know, you probably did mess up, but there's still an opportunity to make some progress!’”

Of course, Oster is a human being herself and has had to make parenting decisions like the rest of us. Her kids went to daycare; she breastfed for a year per child; she chose unmedicated births (“I’m totally glad I did that, even though there’s no point… It was just like, let’s see if I can do it!”); much to the chagrin of many a gentle-parenting advocate, she did sleep training. “One of the things people say [when they’re criticizing my books is]: You're just trying to defend your own choices. Actually, I don't need to defend my choices. Those are the choices that I made based on the preferences and constraints that I have. And I'm actually very confident that they were the right choices for me. And I don't care if you also make them, basically. I genuinely think that there are different people who are going to make different choices… I would like to help people make choices that work for them.”

If she could go back in her own parenting history, she says, “I wish I’d given myself more of a break.”

“I breastfed both of my kids until a year, and I worked really hard to do that,” she says. “And I did all kinds of stuff to try to make that work, particularly with my first kid who was a pain in the ass about it. And you know, I still very much understand the temptation to be like: Well, I worked so hard for this, it better be important.” According to her own data analysis, however, the benefits of breastfeeding are marginal at best — and those much-touted advantages in IQ disappear entirely when the numbers are balanced. Is that a bummer? She laughs. “Bummer isn’t exactly the way I’d put it,” she says, but she thinks she put herself under far too much pressure in the moment. Sometimes, she says, there’s “a feeling of like, the act of suffering is part of the sacrifice of parenting. And I think, you know, it’s not like sometimes parenting isn’t a sacrifice, but we should be picking the sacrifices that matter.”

That brings us back to the 12-meter tapeworms, and specifically the reason she’s been reading about them all morning. The latest parenting craze she’s become aware of is the “parasite cleanse,” a fad diet exploding throughout parenting social media wherein people with children who have autism or ADHD or developmental delay claimed they have “cured” them with the right diet, supposedly one that will starve off the secret parasites that have been causing all the problems. This, Oster says, is the part of her job that gets her out of bed in the morning: “We decided I was going to write about parasite cleanses, and I was delighted to get the opportunity to learn about parasites, like learn some things I didn’t know, look into the research on these cleanses, figure out how to explain — the challenge of: How do I help people understand what is going on with parasites, but also why taking a bunch of herbs is stupid?”

The sacrifice of the parasite cleanse is clearly not worth it, in other words. But Oster understands that “when stuff is going wrong with your kids, all you want is a way to fix it.” There is a real kindness to her pragmatism, a clear compassion for the mothers and the children who she’s addressing when she writes. When I ask her if people DM her about their individual children’s problems, she immediately replies: “All the time.” In the early days, she adds, she’d respond to every one. Now, the volume of messages makes that impossible — but she’ll still do it every once in a while. This week, for instance, she told a heavily pregnant woman on Instagram that it was fine to have a can of Diet Sprite.

Probably the biggest misconception about Oster as a person is that she is a relaxed parent herself, simply because she wrote a book (Cribsheet) with the subtitle “A data-driven guide to better, more relaxed parenting.” One time, she says, she and her husband were at a local neighborhood event and someone familiar with her work came up to her and said: “You must be the most relaxed parent!” She shakes her head. “And my husband just started to laugh and he was like: She's not even the most relaxed person standing on that square of asphalt!”

In many ways, it’s reassuring to hear that Oster is as anxiety-ridden as the rest of us — not just because it makes me feel more normal, but because I don’t want a relaxed person working through medical data any more than I’d like a relaxed pilot flying my plane or a relaxed surgeon doing my open-heart surgery. The problem with parenting is that the stakes are so often life and death. That makes every decision potentially agonizing. It also makes it very hard to write about parenting without provoking the full spectrum of emotions from your audience.

It’s easy to understand why it’s hard to be an economist and a writer who focuses on parenting, in other words. But what, in Oster’s opinion, is the hardest part about being a parent? She thinks for a few seconds. “The fact that the thing that is the most important to you in the world is out of your control. Just the vulnerability that comes with, like, what if something happened to your kid? I think genuinely that is the hardest part.”

Is working with data a way to wrest back some semblance of control over a fundamentally uncontrollable situation? “Yes, totally. But it’s still the thing that keeps you up — and there’s no way to work yourself through that or whatever. It’s just like: Yeah. Sit with that.” Across the world, so many of us — over 2 billion of us — do sit with that every single day. And in the background, Oster keeps at it — diligently raking through the numbers; reading through the studies; separating out fact from assumption; feeling the anxiety so that, maybe, the rest of us don’t have to feel it quite so much.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments