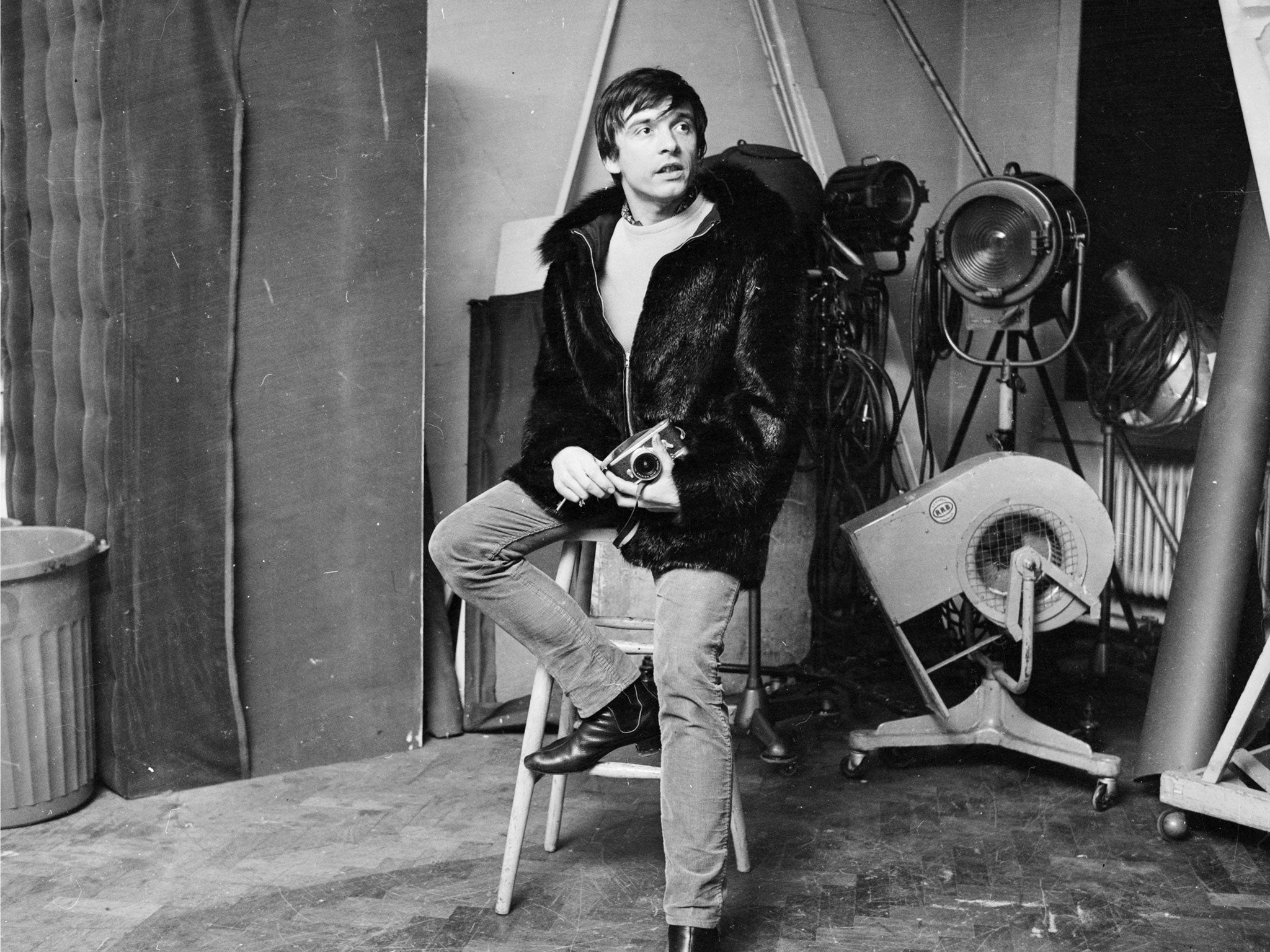

David Bailey introduced us to the concept of the portrait photographer as style arbiter and sex god

John Walsh on the era-defining photographer, 78 today

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Depending on which baby-boomer you talk to, David Bailey is either the man who invented the 1960s by memorialising its most vivid characters – Mick Jagger, the Beatles, Cecil Beaton, the Kray twins – in democratic, monochrome close-up; or the man who personally embodied the 1960s, a working-class kid from East Ham who stormed the lofty heights of fashion with just a camera and a beautiful girlfriend called Jean Shrimpton. He was a scowling, socially mobile rude boy who photographed the new world order and made it look good.

Despite many handicaps – he suffered as a child from undiagnosed dyslexia and dyspraxia, and left school at 15 with no obvious future – he rose by determination and sulky self-belief. He bought a Rolleiflex camera while on National Service in Singapore, became a studio dogsbody back in London, and wangled an assistantship with the fashion-shoot king, John French. At only 22 he was contracted to Vogue – he shot 800 pages of editorial for it in a single year and, with Terence Donovan and Brian Duffy, became part of "the Black Trinity" of celebrity snappers. He introduced London society to the concept of the portrait photographer as style arbiter and sex god, as immortalised by David Hemmings in the 1966 Michelangelo Antonioni movie Blow-Up.

In later years he took to photographing rock stars (notably at the Live Aid concert in 1985), directing documentaries and TV drama, and branching out into sculpture. He has regularly published photography books featuring his third and fourth wives, Marie Helvin and Catherine Dyer, in exotic locations and ever-wilder maquillage and tribal markings. He shows no sign of stopping, and in 2001 was awarded an OBE. But his finest hour was the early 1960s, when he and "the Shrimp" became simply the lens and the face of everything Modern.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments