Study reveals that a lot of psychology research really is just 'psycho-babble'

Of 100 studies, more than half could not be reproduced using the same method

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

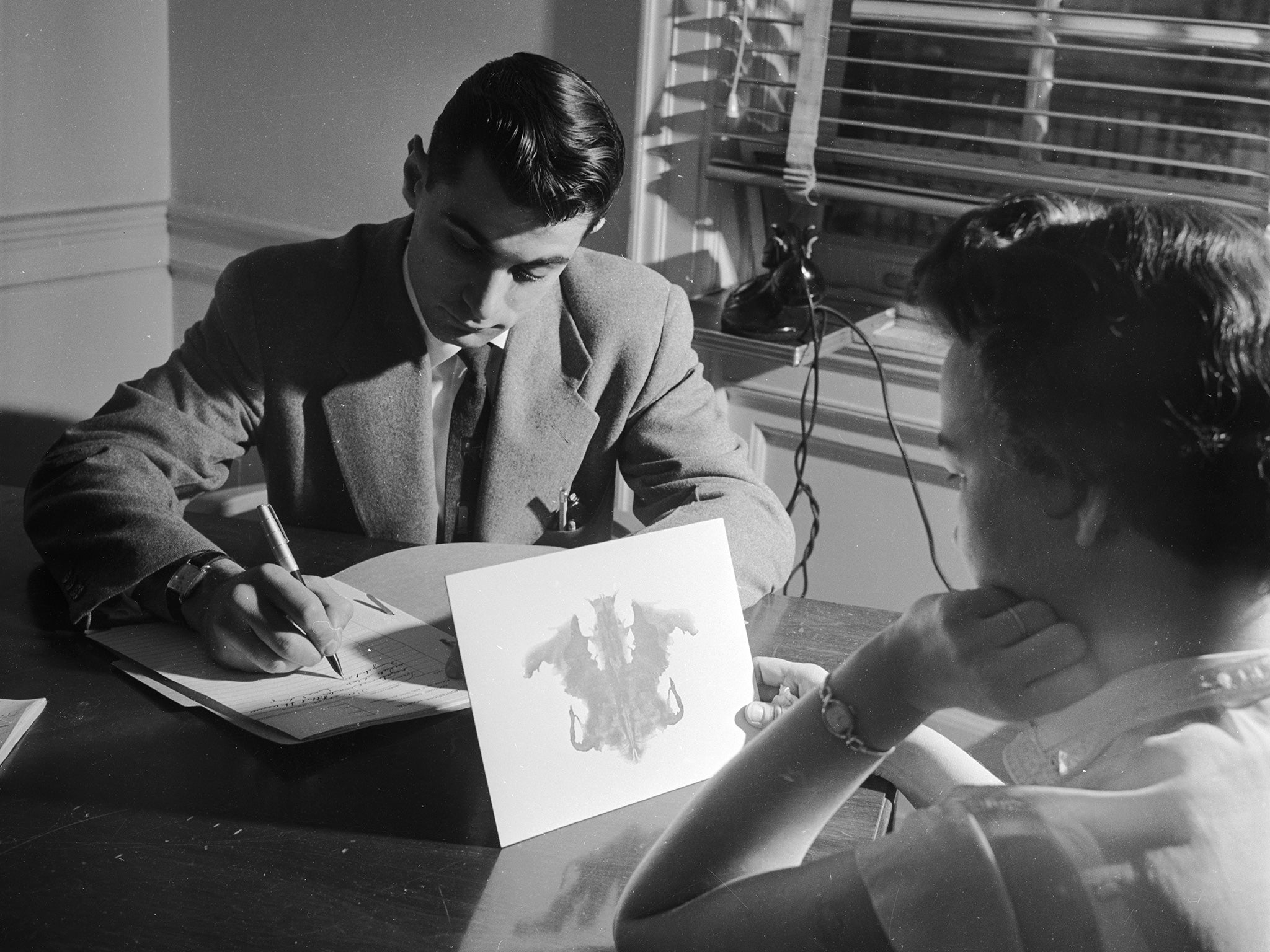

Psychology has long been the butt of jokes about its deep insight into the human mind – especially from the “hard” sciences such as physics – and now a study has revealed that much of its published research really is psycho-babble.

More than half of the findings from 100 different studies published in leading, peer-reviewed psychology journals cannot be reproduced by other researchers who followed the same methodological protocol.

A study by more than 270 researchers from around the world has found that just 39 per cent of the claims made in psychology papers published in three prominent journals could be reproduced unambiguously – and even then they were found to be less significant statistically than the original findings.

The non-reproducible research includes studies into what factors influence men's and women's choice of romantic partners, whether peoples’ ability to identify an object is slowed down if it is wrongly labelled, and whether people show any racial bias when asked to identify different kinds of weapons.

The researchers who carried out the work, published in the journal Science, said that reproducibility is the essence of the scientific method and more must be done to ensure that what is published can be replicated by other researchers.

“Scientific evidence does not rely on trusting the authority of the person who made the discovery. Rather, credibility accumulates through independent replication and elaboration of the ideas and evidence,” said Angela Attwood, professor of psychology at Bristol University, who was part of the reproducibility project.

There is growing concern about the reproducibility of scientific findings, especially in the medical journals where there is great emphasis on “evidence-based” medicine. The levels of statistical significance needed in some fields of research, such as particle physics, are much higher for instance than those employed in “softer” fields such as psychology and medicine.

“For years there has been concern about the reproducibility of scientific findings, but little direct, systematic evidence. This project is the first of its kind and adds substantial evidence that the concerns are real and addressable,” said Brian Nosek, professor of psychology at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, who led the study.

The researchers who tried to reproduce the findings in the 100 published studies said there were three possible reasons for their failure to replicate the results. The first is that there may be slight differences in materials or methods that were not obvious in the published methodology.

The second is that the replication failed by chance alone, and finally that the original results might have been a “false positive”, possibly as a result of researchers enthusiastically pursuing one line of inquiry and ignoring anything that may be inconsistent with it – rather than outright fraud.

Professor Nosek said that there is often a contradiction between the incentives and motives of researchers – whether in psychology or other fields of science – and the need to ensure that their research findings can be reproduced by other scientists.

“Scientists aim to contribute reliable knowledge, but also need to produce results that help them keep their job as a researcher. To thrive in science, researchers need to earn publications, and some kind of results are easier to publish than others, particularly ones that are novel and show unexpected or exciting new directions,” he said.

However, the researchers found that some of the attempted replications even produced the opposite effect to the one originally reported. Many psychological associations and journals are not trying to improve reproducibility and openness, the researchers said.

“This very well done study shows that psychology has nothing to be proud of when it comes to replication,” Charles Gallistel, president of the Association for Psychological Science, told Science.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments