What Tony Blair has told Keir Starmer about how to deal with Donald Trump

In answer to questions from students at King’s College London last week, the former prime minister seemed to outline the advice that he is giving his successor, writes John Rentoul

Keir Starmer needs an “even more powerful No 10 than it was in my day”, Tony Blair told students at King’s College London last week – the day after Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs announcement. “When I was prime minister people wanted the system improved,” he said. “We did improve it. Public services got better. Today they want the system changed. That is a fundamental difference, and you’re not going to be able to do that without a really strong No 10.”

Voters are more impatient with politicians today, he said, and argued that new technology is the only way of meeting those demands: “Today you’ve got to have a strong centre, and you’ve got to be driving this application of technology to government and public services from the centre.”

He said: “You’ve got a choice today if you are in politics – you’re either a disruptor or you’re going to get disrupted.” It is a mark of his influence over the current prime minister that this phrase appeared in Starmer’s address to a special political meeting of the cabinet in February.

“Right now you can see with the Doge experiment in the US: that is a disruption – you punch a hole in the wall and see what happens,” Blair said, referring to Elon Musk’s controversial appointment to head the Department of Government Efficiency.

Blair did not seem to think much of it – “Let’s see what happens with it” – but he went on: “If conventional politics wants to get traction today it needs to provide a way of really changing the system, and I think technology is the instrument to do that, but it has to be driven from No 10, an even more powerful [government] than it was in my day. And it was by the end of it quite powerful. A lot of people didn’t like it, but if you don’t drive it from the top it never gets done.”

Funnily enough, the official briefing to journalists of what Starmer told the cabinet on Tuesday sounded as if it had been dictated by Blair: “He [the prime minister] emphasised digital reform would be critical in transforming the state.”

However, Trump’s declaration of a trade war the day before the class complicated the advice that Blair offered his successor: “I don’t really understand the intellectual argument behind the tariff policy. But I think we have to wait and see how it settles down – if it does settle down...”

Blair appeared to echo Starmer’s “cool heads” approach: “For the UK we are going to have to decide whether to retaliate or not. Probably not. I don’t think it is in the UK’s interest to do that. The risk is if you end up with a trade war [involving] Europe, America and … countries of the far east, I don’t know where it ends. I’m hoping somewhere in there is a plan.”

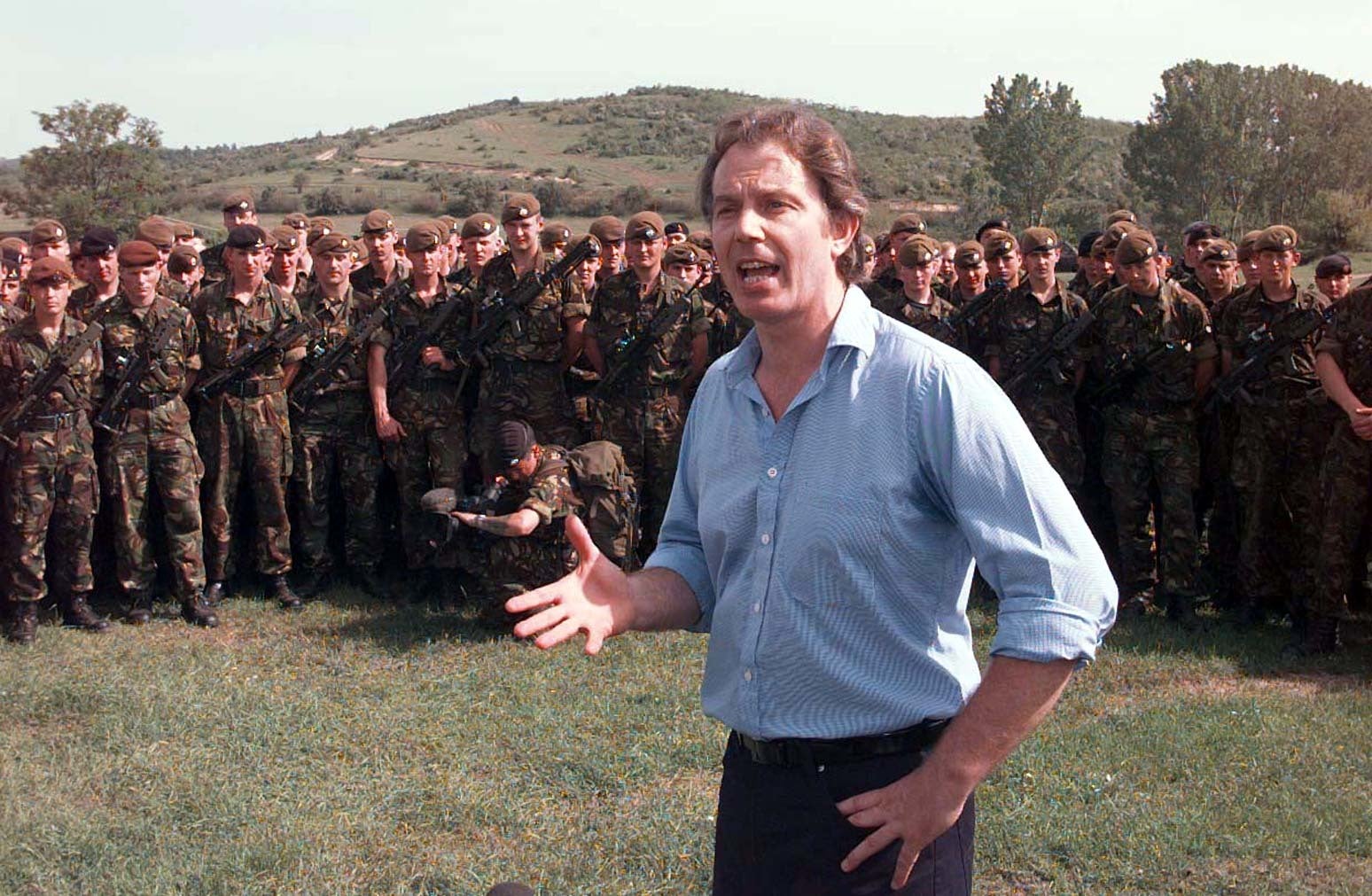

Having dealt with the first Trump administration over the Abraham Accords (the normalisation of relations between Israel, the UAE and Bahrain in 2020) and over the Balkans, Blair reflected, “I have to say I found them very easy to deal with.” He said: “I made it my business to get with whoever was American president because that was part of my job. I also found getting on with the first Trump administration very easy. But obviously the tariff thing is going to be a disagreement.”

Answering students’ questions, Blair claimed to have foreshadowed Trump’s withdrawal of support for Ukraine. The former prime minister explained that a large part of managing the war in Kosovo in 1999 involved negotiating with Bill Clinton, “because the Americans did not want to get involved”.

He said: “It’s of contemporary interest that I began European defence with the French government at St Malo, after the Kosovo war, precisely because it became clear to me that we could never have done it without the Americans, and that 90 per cent of the assets were American. I took the view after that that, ‘This is crazy: what happens if the Americans decide they don’t want to be part of something? Then where do we go? We wouldn’t be able to do anything.’ But European defence got caught up in a whole lot of Eurosceptic arguments. So it didn’t go where it should have gone, which is how do we create the capabilities that are needed if for any reason America decides to step aside.”

While some of the lessons from his time in government are relevant today, others are now slipping into history. He was asked about the causes of the intelligence failures in Iraq. “People forget this,” he said. “There had been a huge build-up of intelligence about Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction for a long time, and the first military action that I took was with Bill Clinton in Iraq in 1998. There were UN inspectors going in and out. It was the only country that had used chemical weapons since the Second World War, both in the Iran-Iraq war [and against its own people].

“The intelligence failures were a combination of the strong belief that people had that because he had used them he would use them again, and people feeding information out of Iraq because they wanted military intervention that would topple the dictatorship.”

Blair was also asked to give a “definitive answer” to a question that has engaged our students since Professor Jon Davis and I set up the course in 2008: did he really want to join the euro? “The definitive answer is this,” said Blair. “I wanted Britain to be at the heart of Europe, to be a key leader in Europe. I would have been happy to be part of the euro – provided that the economic case was what we used to call a compelling case.

“And the trouble was because the British economy moved in different synchronicity from the French and German economies, it was never clear that that compelling case was there. And I never thought that we could win a referendum. I didn’t think it was possible to take Britain into the euro without a referendum – and I didn’t think it was possible to win it unless you were able to say the economic case was overwhelming. Now, in time that might have changed. And in time it might have been that it became clear that it was in Britain’s interest to be part of the single currency. But I thought that what was important was that we were always in principle in favour of joining if the economics were right.

“So that is the situation. If the economic case had been there, so that we were able to go out and tell people that economically it’s clear that this is the right thing to do, a bit like the original case for joining the European community, we could have done it, and maybe even won it – although the reason for saying there should be a referendum was simply because I thought it was politically impossible to do it any other way. Do I believe that referendums are a very good idea in deciding things like that? No, frankly. But I couldn’t even have got it through cabinet if I tried to do it without a referendum.”

This account by Blair of his own views seems consistent to me with the analysis offered by Ed Balls – now also a professor at King’s – that Blair wanted to keep his options open, and had to appear to want to join if Britain was to be “at the heart of Europe”, but knew a referendum was unwinnable. The difference between Blair and Gordon Brown on the euro was therefore more about the difference between sounding positive or negative than it was about the issue itself (on that, Blair seems lukewarm: he would have been “happy” to have been part of the euro).

But Blair insists that there were policy differences between him and Brown, and that these hold a lesson for Labour today: “Historically, I have a very clear view of what the problem for Labour has been. Labour in government has usually been brought down by itself and by opposition to having to make difficult decisions, because all governments do. Labour now forgets that, thinking of some nirvana where no difficult decisions have to be taken. And opposition to the leadership is usually outside the tent.

“Gordon wasn’t ‘opposition’, but he was a focal point for a different approach, more traditional Labour than New Labour, or real Labour as people sometimes called it, and it was better it was him, highly intelligent, himself a very effective political force, inside, than it would have been if he had been outside altogether, or it had been someone else that had emerged and took that mantle and was constantly battering the government.

“And so, it was a coalition and we did more or less keep it together. It was difficult. Believe it or not, I didn’t resent it as much as a lot of the people around me – I thought, ‘It’s politics.’ But the difference between old and new Labour was important, and it was ultimately a policy issue, because my view was and is that it’s only a version of that political position that can win power sustainably.”

It was a coalition that did not survive Brown’s defeat in 2010. “What I’m absolutely sure about is that if Labour had chosen the other Miliband brother I don’t think Brexit would have occurred. Because we would have had a Labour Party that was a credible contender in the 2015 election,” Blair said. “Not that I don’t like Ed [Miliband], because I do – I think he showed a lot of character in the 2015 election, with all the attack he was under, but I think he was not in the right policy place to win.”

Blair argued that the position adopted by New Labour was and remains the only way to win, but accepted that the environment has changed, and that it has become harder for “conventional politics” to offer solutions that satisfy the voters. Part of this is the change wrought by social media, which he said “is really hard”. He mused that “maybe in the end, communication on social media is just the same thing, it’s just a different medium, but I do think that makes it a lot harder”. A problem of social media, he said, is the tendency to frame decisions “in terms of deception or conspiracy, rather than: you’ve got to decide what to do”, he said.

He traced the rising distrust of the motives of leaders back to the 1970s: “In my view, Watergate did a lot of damage. In the sense that it was bad enough but the sense of what happened was actually worse than what happened. And you ended up in a situation where for ever afterwards everyone wants to find a conspiracy.”

John Rentoul is a visiting professor at King’s College London; he teaches the ‘New Labour Years’ module with Dr Michelle Clement, as part of the MA in government studies under the leadership of Professor Jon Davis

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments