My question to the White House about Tren de Aragua gang members caused a flare-up. This is why I asked it – and why it matters

Press secretary Karoline Leavitt didn’t appreciate my question about how the government is making sure innocent people don’t get misidentified as dangerous gangsters – even saying ‘shame on you’ – but there’s a very good reason I asked, writes Andrew Feinberg

Since Donald Trump was sworn in for a second term in January, one of the easier ways to get answers from his top aides about news of the day is to hang out on the White House’s driveway near a row of television camera positions that White House reporters call Pebble Beach. That’s where administration officials have to pass by to get to or from any appearances they want to make on TV channels.

That’s where I was on Monday, standing with other members of the White House press corps, when Karoline Leavitt stopped to take a few questions after an early afternoon interview on Fox News.

After she answered a few queries from colleagues on Trump’s planned April 2 tariff spree — something the president has taken to calling a “liberation day” even as most business leaders are shuddering at the possibility of new import taxes that will raise prices for American consumers — Leavitt indicated that she would take a question from me on behalf of The Independent.

I tried asking her about a government document that had been filed on a public court docket in litigation seeking to halt Trump’s use of the Alien Enemies Act to deport Venezuelans who the government has accused of being part of Tren de Aragua, a violent Venezuelan street gang which the Trump administration has designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization.

To be sure, Tren de Aragua — or TDA for short — is not made up of nice people. What I wanted to know was how the government is determining who is and is not a member — and what happens if the government gets it wrong. This matters because the Trump administration has struck an agreement with El Salvador’s president to house alleged TDA members who’ve been deported from the U.S. in a Salvadoran prison built to house members of the gangs that have long plagued that country.

According to the document, Department of Homeland Security officials can classify someone as a deportable TDA member if they garner eight or more points from a set of classification criteria. Some of them are serious and straightforward, such as whether the person in question has identified themselves as a TDA member (10 points), spoken to other TDA members about gang business on the phone (10 points), engages in emails or text communications with other members (six points) or participates in human smuggling or other crimes alongside TDA members (six points).

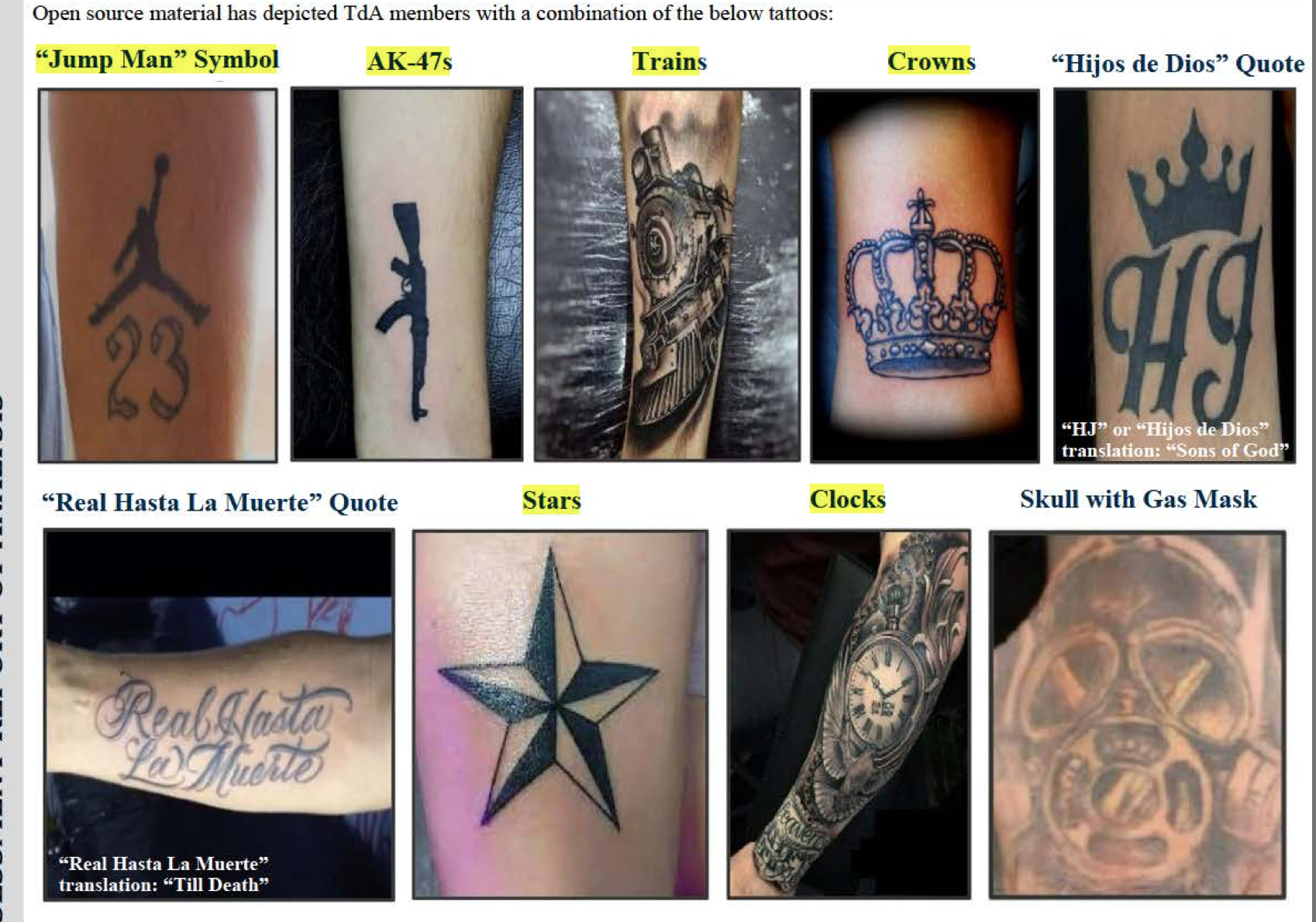

But other criteria on the classification document are harder to pin down. It states that having “tattoos denoting membership in or loyalty to TDA” can get a person four points, but TDA is actually an outlier among South American criminal gangs because it does not use tattoos to identify members in the same way others, such as MS-13, are known to do.

Another criteria assigns four points to anyone “displays dress known to indicate allegiance to TDA,” which according to court documents is a broad category encompassing popular streetwear brands.

As my colleague Alex Woodward has reported, this means a person could be classified as a gang member under the AEA simply for wearing the popular Michael Jordan-branded “Jumpman” clothing line if they have tattoos that DHS interprets as indicating gang membership.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers also appear to have wide discretion to deport alleged gang members if that score is a few points short after consulting with supervisors and “reviewing the totality of the facts.”

And court documents and affidavits from attorneys for dozens of people who were deported to El Salvador suggest that ICE has repeatedly targeted Venezuelan immigrants for their tattoos, regardless of their meaning, as evidence of their alleged affiliation with Tren de Aragua.

What I wanted to ask Leavitt was whether there are any contingencies in place to get people out of that Salvadoran prison if it turns out that the U.S. government mistakenly identified them as a TDA member.

But Leavitt wasn’t interested in answering. Instead, she accused me of “trying to cover” for violent gang members and impugning the reputations of ICE and DHS officials.

“You are questioning the credibility of these agents who are putting their life on the line to protect your life and the life of everybody in this group?” she added. “And their credibility should be questioned? They finally have a president who is allowing them to do their jobs and God bless them for doing it."

“Shame on you and shame on the mainstream media for trying to cover these individuals,” she added.

Do I have reason to question the credibility of American immigration agents? No.

But because the people who the U.S. has deported under the AEA had no opportunity to contest whether or not they were gang members before being sent to a Salvadoran gang prison, I have to account for the possibility that officials could get it wrong, especially when all they need to do to classify someone as a member is to find someone wearing a Michael Jordan sweatsuit with a tattoo.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments