‘People were getting a bit yippy’: The real reason Trump talks the way he does

The world might think the US president’s choice of words is curious, but it makes total sense when you look at the revolutionary spirit of the founding fathers, says Robert McCrum, who explains why Trump is the true voice of America whether we like it or not...

A few weeks ago, I received a call from Voice of America (VOA), notorious during the Cold War for its loony tunes anti-Soviet propaganda. Happily, those brave old days lie in the dustbin of lost causes, but the human animal is never exempt from history. In the bitter spring of 2025, VOA – now more of a television station than a radio arm of American foreign policy – was reporting on the frenzy of Trump’s first 100 days, in particular the president’s executive order declaring that English should be the official language of the United States.

In the perverse, and sometimes baffling, style of Trump 2.0, this may feel peculiar for a president known for his curious choice of words (the tariff retreat, we are told, was made because the markets were getting a bit “yippy”) and equally so that this channel should have migrated from super-power rivalry to the politics of the lexicon. But, as the author of The Story of English (1986), I told the VOA researcher I had plenty to say about English as the official language of this embattled republic.

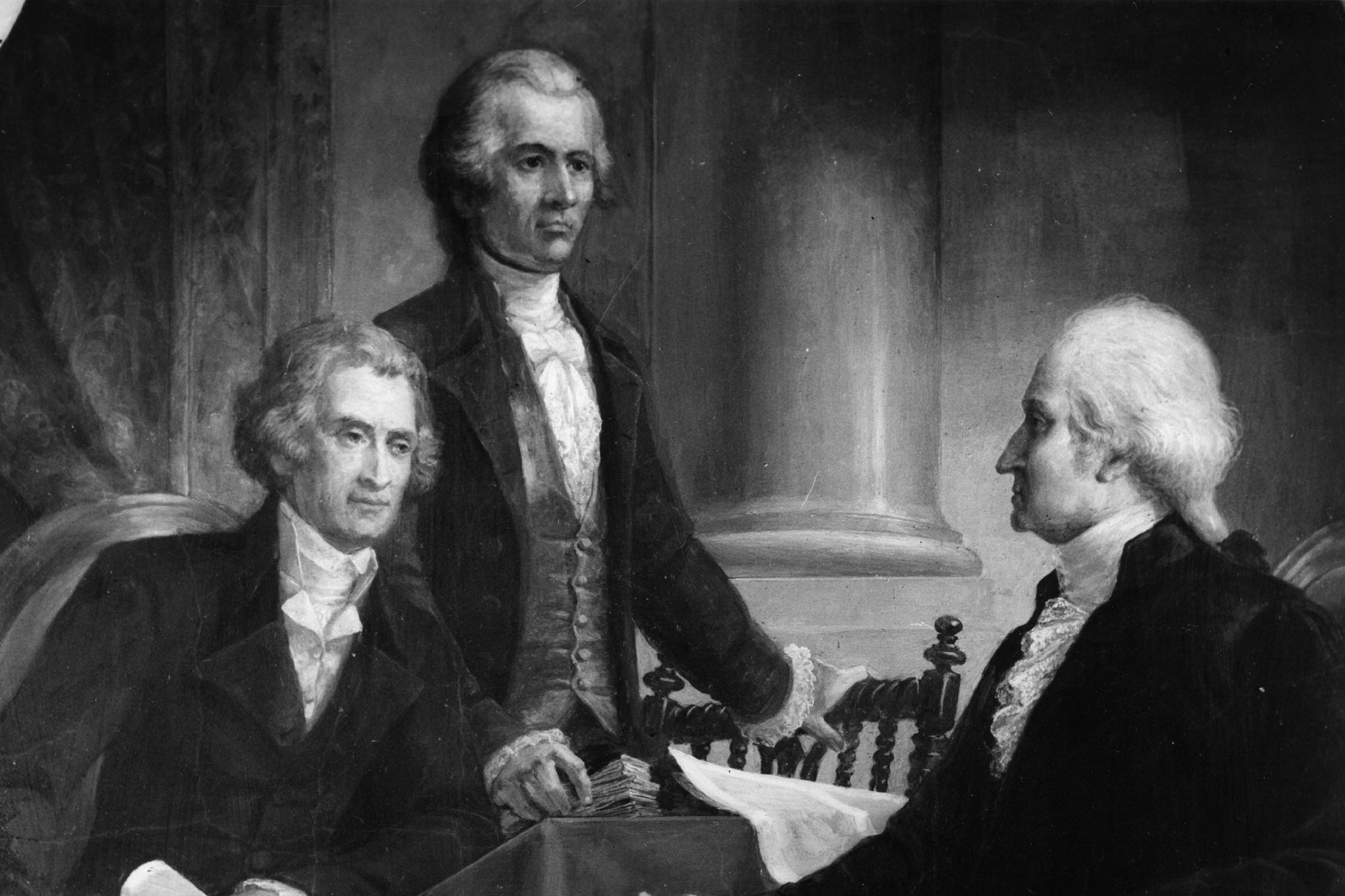

Since the Declaration of Independence asserted the rights of “We, the people”, words have played a vital role in the remaking of American society. According to one French diplomat, who travelled with General Washington in the 1780s, there was a fierce appetite among some American firebrands for “a new language”, with “some persons desirous… that Hebrew should be substituted for English”.

As well as flirting with the language of the Bible, one or two hot-headed legislators even toyed with the idea of adopting Greek as America’s official language. This proposal was rejected on the grounds that it would be “more convenient for us to keep the language as it was, and make the English speak Greek”.

This was practical. The first census of 1790 counted some four million Americans, 90 per cent of whom were descended from English colonists. By contrast, the 2020 census counted 18.7 per cent of the population (some 62 million) as Hispanic speakers who, in states like Florida and parts of Texas, now form a Spanish-speaking majority. It’s this that gets Trump’s goat, and stirs his atavistic revolutionary instincts.

Such reflections on the English language in the USA also give a new perspective on Trump’s retrogressive, counter-revolutionary appeal to the fiery origins of the republic. The DNA of 1776 continues to nourish all kinds of radicalism – good and bad. It’s worth remembering, amid the torrent of words spewing out of Trump’s White House, that America was a society invented, planned, and first fabricated out of words.

The founding fathers’ pitch was always 10 parts advertising to one part revolution. Then, we had Thomas Jefferson’s “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”; today, we have Trump’s “Make America Great Again” and “Liberation Day”.

Language is integral to Trump’s vicious sway: he is the master of lies, self-promotion, vilification, character assassination, and gangsterish propaganda. Under this administration, the US has become the republic of slander and half-truths. The Washington Post, indeed, logged a grand total of 30,573 untruths during his first term – a level of official lying (aka falsehoods) unprecedented in US politics.

During this week’s market meltdown, Trump’s fabrications have soared to a new stratosphere of mendacity: Trump said the United States had a $250bn trade deficit with Canada (it’s actually $55bn), and that Canada “imposes a 250–300 per cent tariff on many of our dairy products” (also not true). He also claimed the US “took in hundreds of billions of dollars” from China thanks to tariffs he imposed during his first term (not true), and that tariffs had never before been collected on Chinese goods before he took office (also false).

When the president spoke at a dinner in Washington about world leaders “kissing my ass” to make trade deals, his syntax buckled under the strain: “You don’t negotiate like how I negotiate. I know what the hell I’m doing.” At the same time, Trump coined a new term for “the weak and stupid people” who opposed him. They were “panicans”, he declared.

There’s no need to be naive about this. Ever since Aristotle, we’ve known that politics involves dirty tricks, muck-raking, spin, calumny, brutal betrayals and intimidation. But there have been niceties, too. “Niceness” is sanctioned by the Oval Office.

During these first hundred days, America and its global audience have been subjected to an awful lot of smiling – a Pennsylvania Avenue rictus – oodles of euphemism, and slick projections of fake optimism. This has been particularly true in a week when global markets have plummeted to unprecedented depths. Yesterday, we were told the bond market looked “beautiful”. This was just a few hours after Trump insisted that “everything is going to work out well”, adding that “the USA will be bigger and better than ever before”.

In Trump’s words, his administration has been “making nice” with US trading partners (but not China). In the 47th president’s world, when people aren’t making nice, they are just nasty. Hello Kamala Harris, Nancy Pelosi, Hillary Clinton, and anyone else who may ever have pointed out the president’s flaws. As usual, such corruptions of language are mirrored by the rottenness running through the 47th president and his gruesome associates.

But back to the founding fathers: Trump also gets a boost from tuning into America’s foundation myth as the home of non-conformity. The pilgrim fathers were not a shipload of amiable, pipe-smoking contrarians or fuzzy cross-patches. They were zealots who risked their lives – and their families’ futures – to cross the Atlantic just before the atrocious winter of 1620–21 to set up a new society dedicated to an exceedingly rare kind of madness: a way of life shaped by, and devoted to, the word of god.

Nevertheless, the historical dimensions of Trumpism – and the 47th president’s mad, but unconscious, evocation of the worst lessons from lost times – have inspired, in his critics, an appetite for another kind of language: the warning from history. Bible-bashing in the USA has always inspired a peculiar kind of intimidation rarely seen this side of the Atlantic.

As Alan Rusbridger described it in his recent Independent article, a new and viral outbreak of cowardice in the face of Trump’s triumphalism has become alarmingly contagious with echoes of the witch hunts of Nixon. This so-called “great grovel” (the term comes from Politico) now involves tech billionaires such as Zuckerberg, law firms in New York and Washington, great universities (Columbia and Harvard), and media empires like ABC, among many others.

Language is integral to Trump’s vicious sway: he is the master of lies, self-promotion, vilification, character assassination, and gangsterish propaganda

Worse than the great grovel, perhaps, is the deafening silence among prominent Democrats with impeccable track records. Barack Obama first made his reputation as a writer of honesty and insight, a warrior for truth, and a master communicator.

Sadly, “yes we can” seems to have become “maybe I won’t”. Until this week’s trading apocalypse, he had been almost invisible. Finally, as America’s Democrat elder, Obama began a cautious fightback. Speaking at Hamilton College in New York, he considered Trump’s actions and reflected: “This kind of behaviour is contrary to the basic compact we have as Americans. Imagine if I had done any of this.”

This is a good start, but many will hope he goes further. Is it too much to wish that Obama mobilises his formidable rhetorical gifts to send a signal to every tech millionaire, every college principal and campus, every TV executive, and also to the standing army of America’s lawyers that, in a country founded also on the language of the enlightenment, every word counts?

In the event, I never had the opportunity to rehearse these thoughts to Voice of America. Trump signed an executive order slashing the channel’s budget and, on 14 March 2025, almost all of VOA’s 1,300 journalists, producers and assistants were placed on administrative leave. The next day, several VOA foreign-language broadcasts replaced news and other regularly scheduled programming with music; simultaneously, the VOA website was frozen.

Trump’s “hundred days” remains a moving target. The real battle – yet to come – will be fought out in courtrooms, polling booths, social media platforms and broadcasting studios, between now and the midterms. And after that, no doubt, throughout the two-year cycle of the 2028 election – with just one double-edged weapon: American English.

Parlez-vous Trump? The president’s favourite words

Beautiful: “We should immediately stop sending our beautiful American tax dollars to countries that hate us and laugh at our president’s stupidity!” On coal: “And we’ve ended the war on clean, beautiful coal, and we’re putting our miners back to work.” On himself: “If I took this shirt off, you’d see a beautiful, beautiful person.”

Nice: On Starmer: “I’m going to see him in about an hour so I have to be nice right? But I actually think he’s very nice.” On Prince William: “He looked really, very handsome last night. Some people look better in person. He looked great. He looked really nice, and I told him that.”

Nasty: On Nancy Pelosi: “I’ve tried to be nice to her because I would have liked to have gotten some deals done… She’s a nasty, vindictive, horrible person.” On Hillary Clinton: “Such a nasty woman.”

Sad: On voters: “Because of me, the Republican Party has taken in millions of new voters, a record. If they are not careful, they will all leave. Sad!” On Jeb Bush: “In the ridiculous @JebBush ad about me, Jeb is speaking to me during the debate, but doesn’t allow my answer, which destroys him – SO SAD!” On The View: “@ABC, once great when headed by @BarbaraJWalters, is now in total freefall. Whoopi Goldberg is terrible. Very sad!”

Winning: As in “we’re going to win big”. “I have a winning temperament. I know how to win.”

Tariffs: As in “I always say ‘tariffs’ is the most beautiful word to me in the dictionary.” Of course, feeling a bit yippy may have changed all that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments