It’s going to take a catastrophic event for AI safety to be taken seriously

Dangerous incidents related to artificial intelligence reached record levels in 2024, but regulation is still lagging, writes Anthony Cuthbertson. Experts warn it could take a catastrophe before we take the risks seriously – but by then it may be too late

The closest the world has ever come to armageddon was the result of a computer error. On the night of 26 September 1983, in the depths of the Cold War, 44-year-old Stanislav Petrov was on duty at a Soviet radar station outside of Moscow when he saw five intercontinental ballistic missiles appear on his screen.

The protocol was to alert his higher-ups of the incoming threat, potentially triggering a retaliatory attack against the US that would lead to all-out nuclear war. But Petrov refused to follow the procedure – he didn’t trust the computer. Petrov, who is now remembered as “the man who saved the world”, was right. The recently installed early warning system had mistaken the sun reflecting off clouds for missiles.

The event is the first incident listed in the AI Incident Database, launched in 2018 to index dangerous moments caused by computing and artificial intelligence systems. These incidents are now on the rise, with a record 253 reported in 2024, and even more projected for 2025.

Some incidents are fatal, like the robot that crushed a worker to death at a Volkswagen factory in Germany, or the growing number of self-driving car fatalities. Others are merely problematic, such as Amazon’s sexist recruiting tool that marked down female candidates, or faulty facial recognition technology leading to wrongful arrests.

Yet despite the surging numbers, some fear that the threat posed by AI will not be taken seriously until something truly catastrophic happens. Dr Mario Herger, a technology trend researcher based in Silicon Valley, calls this an “AI Pearl Harbor” – referring to the devastating surprise attack by Japanese aircraft on a US naval base in 1941 that killed 2,400 people and finally drew the United States into the Second World War.

In a 2021 blog post, Herger wrote that AI safety will only be prioritised when “an attack causes an AI to kill thousands of people or steal hundreds of billions of euros” from a government. “The coming of an AI Pearl Harbor is not inevitable because we cannot prepare and defend against it,” he concluded, “but because – as always – we do not take it seriously until it happens.”

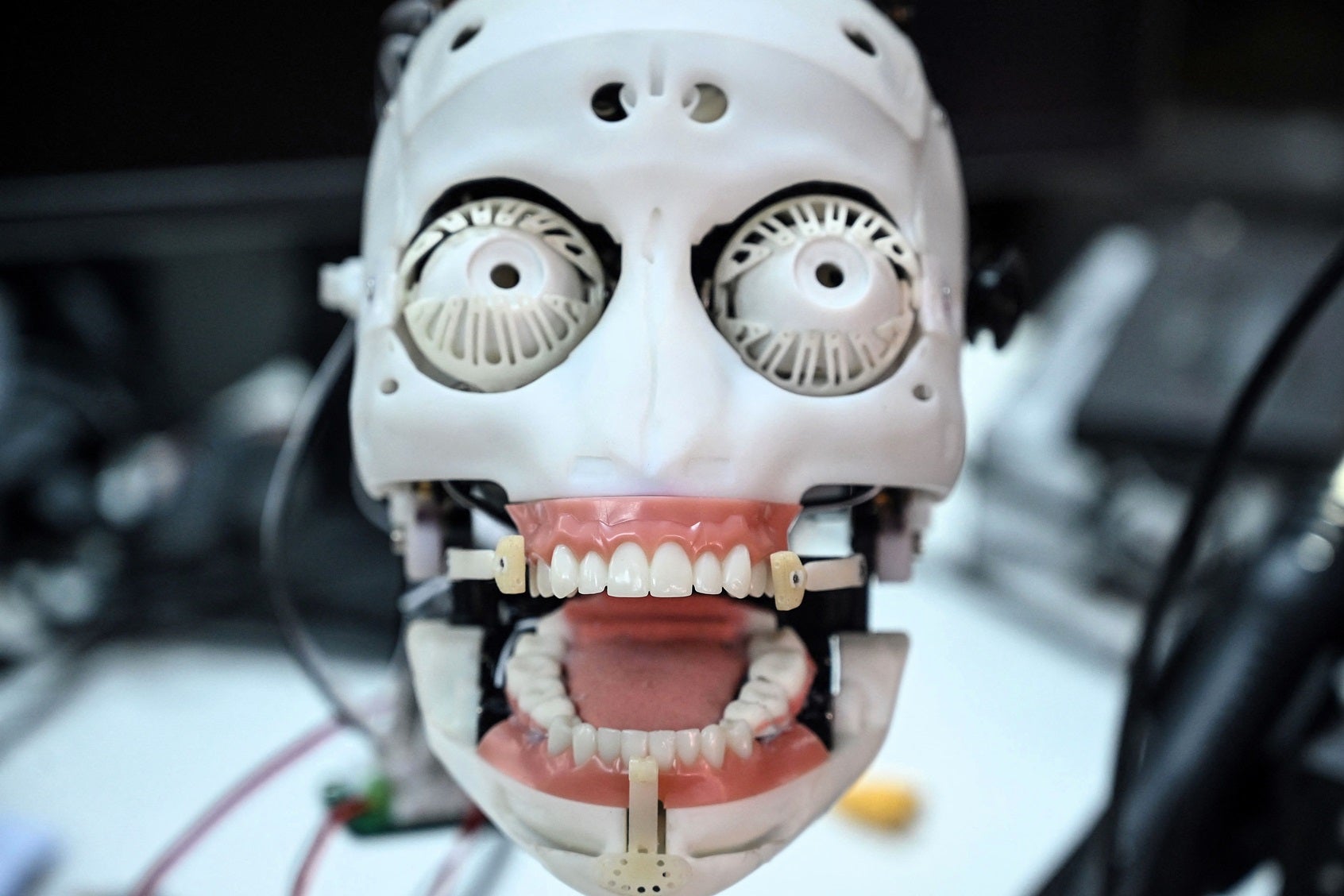

The incident could come in the form of humanoid robots attacking humans en masse due to a glitch, he speculated, or a malicious AI taking control of critical infrastructure to cause deadly blackouts or economic chaos.

Since writing that blog post, the emergence of ChatGPT and other advanced models has seen AI become more prevalent than ever, leading to a massive increase in ways it might happen.

“AI is everywhere, and we will see many more forms of artificial species occupying our spaces,” Herger tells The Independent, pointing to humanoid robots that are now being manufactured at commercial scale, as well as the continued rise of high-tech drones. This means the possible attack vectors are increasing. As always, the worst outcome is very unlikely, but likelier than experts would tell you.”

To counter such threats. leading companies like OpenAI, Google and Meta all have AI safety policies in place to develop AI responsibly. Governments around the world have also intensified efforts to address AI safety in recent years. But as with all technologies, regulation is in a constant state of catch-up with innovation.

In February, leaders from over 100 countries gathered at the AI Action Summit in Paris to come up with a coordinated approach to AI development and safety. And while 60 countries signed a declaration to ensure AI is “open, inclusive, transparent, ethical, safe, secure and trustworthy”, two notable countries refused to: the UK and the US.

AI ethics experts, including David Leslie from The Alan Turing Institute, claimed the conference was more focused on advancing opportunities for economic growth than addressing the real-world risks posed by artificial intelligence.

The recent emergence of advanced AI models from China, like DeepSeek and Manus, has also intensified focus on competition rather than caution.

Dr Sean McGregor, an artificial intelligence safety expert who started the AI Incident Database seven years ago, notes that new AI systems are bringing with them risks that are almost impossible to predict. He likens each new problematic incident to a plane crash, as the issues that cause them are usually only obvious in retrospect.

“I am not surprised to see AI incidents rising sharply,” he tells The Independent. “We are living in the era five years after the ‘first aeroplane’. Only now, all adults, children, and even pets, have their own AI ‘plane’ well before we figure out how to make them reliable. While AI systems are getting safer each year for people to use, they are also entering into new use cases and malicious actors are figuring out how to use them for bad things. Ensuring AI is beneficial and safe for all humanity requires technological and societal advances across all industry and government.”

One possible scenario for an AI Pearl Harbor, according to McGregor, would be a paralysing attack “against all networked computer systems in the world in parallel”. For something like this to happen, it would likely require a form of AI that does not exist – at least not yet.

Nearly all leading AI companies are currently working towards artificial general intelligence (AGI), or human-level intelligence. Once this point is reached – estimates range from months to decades – then the arrival of artificial superintelligence will likely follow, meaning we will no longer be able to even understand the advances being made. It would be capable of doing more damage than any human. And by then, it may be too late to stop.

Sam Altman, the head of ChatGPT creator OpenAI, has frequently expressed his concern that advanced AI could bring about the end of human civilisation. Yet he continually pushes his company to launch products before those working for him believe they are safe to be released.

We are living in the era five years after the ‘first aeroplane’. Only now, all adults, children, and even pets, have their own AI ‘plane’ well before we figure out how to make them reliable

Altman’s defence is that market forces compel it: if new models are not launched, then OpenAI risks being left behind. The other argument often cited by leading technologists is that AI has the potential to do massive amounts of good, and that stifling its development could slow down scientific breakthroughs that could help cure diseases or counteract the worst impacts of the climate crisis.

Even Herger describes himself as a “techno optimist”. He believes AI is generally getting safer, and that problematic incidents are surging simply because more people are using it. “Why? Because AI really is making their lives better and is useful,” he says. “I think AI, like almost all other technologies we ever invented, will make us humans vastly better off. Technologies with good policies have brought us progress that makes us live longer, healthier lives, in cleaner environments.”

AGI has been referred to as the “holy grail of AI” due to its sheer potential, and the race to reach it is fierce. A recent report from researchers at Stanford University in the US found that China is rapidly catching up with the US when it comes to developing human-level AI, with American companies now rushing to release AI products to keep up.

The same report also noted the concerning trend of AI-related incidents rising to record-breaking levels. It highlighted one particular incident from February 2024, in which a 14-year-old boy died by suicide after “prolonged interactions” with a chatbot character. The case was emblematic of the complex ethical challenges surrounding AI, the report’s authors noted, highlighting the risks involved in deploying new products without adequate oversight.

It is this type of incident that could be how a Pearl Harbor-type scenario might play out. Rather than a malicious act like an attack, it could be unintentional. It is also one of the most common forms of harm listed in the AI Incident Database, and with human jobs increasingly automated, this could occur in various critical ways. Had an AI been responsible for Petrov’s job in 1983, for example, an AI Pearl Harbor may already have happened.

Having observed the rise of problematic technology through the AI Incidents Database, McGregor points to one particular path towards disaster: neglect. Just like acid rain, river pollution and oil spills have become symbols of environmental degradation that spur change, he hopes the database will do the same for AI.

“We learned from these environmental incidents, and have spent decades remediating their harms,” he says. “AI can be used to more efficiently remediate environmental degradation, but it poses a duality similar to industrialisation. My hope is that indexing history in real-time will steer society and its technology towards better futures without a need for learning from a Pearl Harbor moment.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments