Learning lines by heart: like having your own private iPoems library

In times of need, the pupils forced to learn poetry as part of a new Government scheme will be deeply thankful for the lesson

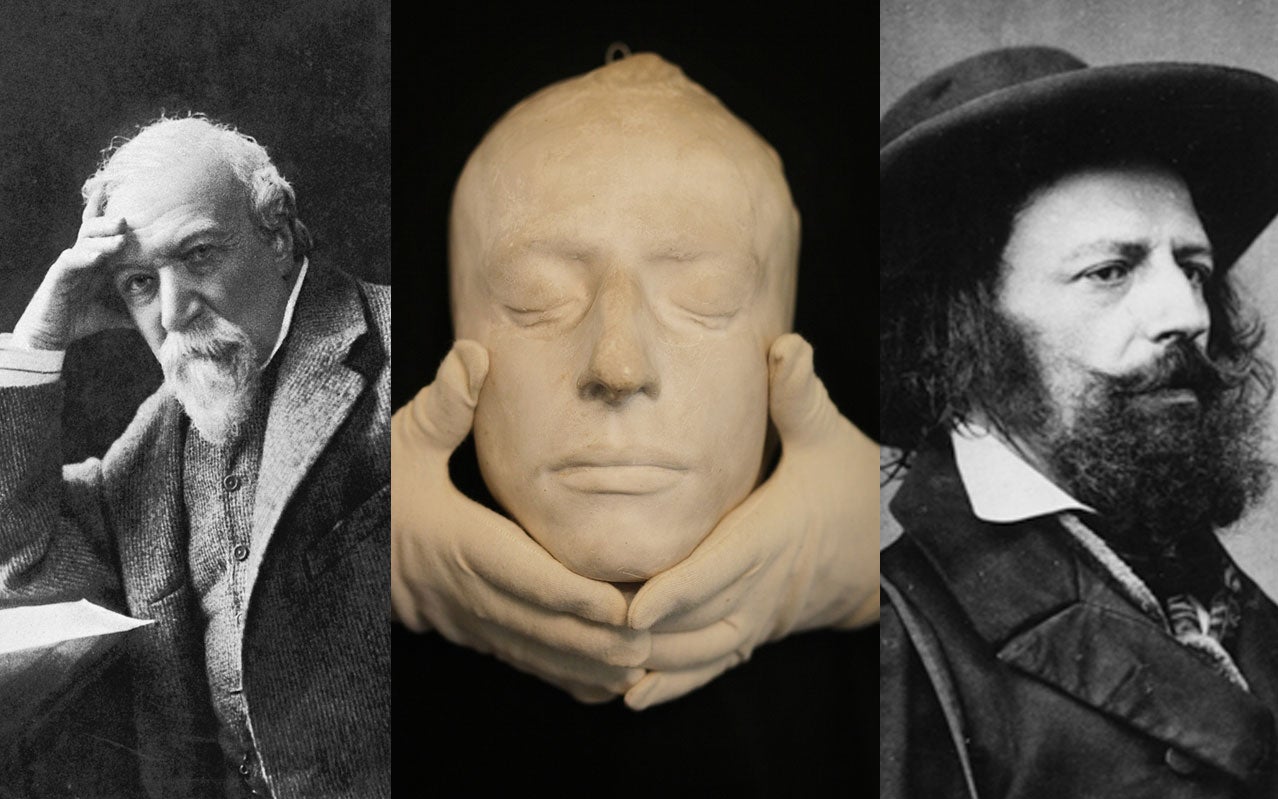

Best news of the week, after the renaissance of Ziggy Stardust, is the launch of Poetry by Heart, the Department for Education’s drive to encourage children to memorise poems. Pupils will compete with each other to learn “The Second Coming” or “When That I Was And A Little Tiny Boy”. School champions will declaim Keats or Browning at oikish rivals from other schools. There’ll be heats and a nail-biting final in April. It’s very Michael Gove – and I’m all for it.

Learning poetry doesn’t come easy. The first few times you try, the repetition drives you crazy. You find fault with the meaning. The first poem I had to learn was “Young Lochinvar”, about a heroic young Scot, of whom we were told: “And, save his good broadsword, he weapons had none;/ He rode all unarmed, and he rode all alone!” It proved impossible to recite it in class without breaking off to remonstrate that, if the man carried a big sword, by what logic was he All Unarmed? But I persevered, and I’m glad I did.

Having a little anthology of poems in your head won’t make you any money (though I once won a £5 bet that I couldn’t recite the whole of “Kubla Khan” by heart) and it’s of limited use in a crowded bar (though fans of Sylvia, the movie about Sylvia Plath, will recall the scene where Ted Hughes and his wacky Cambridge drinking mates recite Byron and Keats to each other from memory, terribly fast). But it means you have beautiful lines embedded for ever in your brain, that will pop out and remind you of their existence at moments when you need help.

The last 20 lines of Tennyson’s “Ulysses” (“…sitting well in order smite/ The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds/ To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths/ Of all the western stars, until I die”) slide unbidden into the mind of the ageing groover who suspects he’s past his best but might risk one more shot. Yeats’s “The Wild Swans at Coole” offers a hit of poetic cocaine (“Their hearts have not grown old;/ Passion or conquest, wander where they will,/ Attend upon them still”).

Bits of Chesterton always cheer you up (“Where you and I went down the lane with ale-mugs in our hands,/ The night we went to Glastonbury by way of Goodwin Sands”). Remembering Hardy’s “The Ruined Maid” in Queensway on a rainy day is a blessing. And being able to quote the climactic bit of “To His Coy Mistress” does no harm in other contexts.

It’s like having your own private internal iPoems library, available for download any time via your memory. It’s like thinking of a favourite painting and being able to pull it out of your pocket and gaze at it. It’s about owning someone’s else’s words, but making them part of your life, your thoughts and your heart.

Where are your tattoos, Ed?

The rise of Vladimir Franz in Czech political circles is a marvellous thing, isn’t it? Here’s a man who doesn’t rely on gimmicks. You can tell his promises are more than skin-deep. Sincerity is written all over his face… Actually, I’ve no idea what possessed voters in the Czech Republic to propel this jolly writer/composer to third place in the Presidential elections, despite his complete lack of political experience or knowledge of economics.

Apparently younger voters are sick of corruption in the party machine and like his platform of anti-corruption, pro-education reforms. But don’t you wish more politicians cut a dash like Mr Franz? A few Polynesian-warrior tattoos on the faces, arms and legs of, say, Ed Balls or Theresa May would give Commons debates the thrust and swirl they so signally lack.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments