There is a way back for Labour – but the party needs to relearn some vital lessons

Editorial: Well within living memory, ‘New Labour’ won a landslide majority based on building a remarkably broad base of support, one that kept it in power for the next 13 years

Even with the best possible spin being applied, the election results thus far are far from encouraging for the Labour Party. Even under conditions of a pandemic and the worst economic slump in 300-odd years, the governing party, mired in sleaze allegations and with a far from glittering record, has emerged from its latest electoral test relatively content.

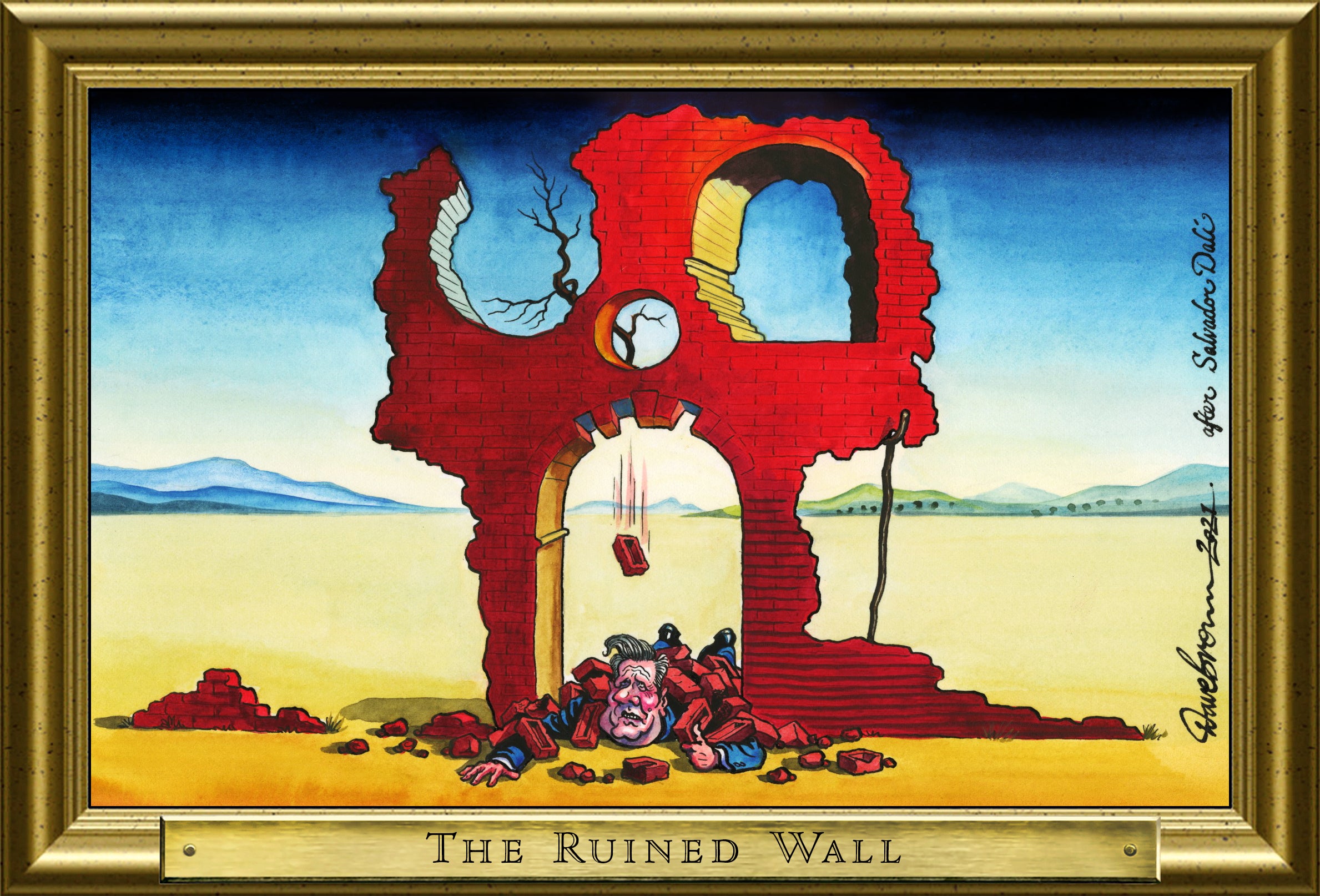

In Hartlepool, Labour not only failed to win back much of the Eurosceptic vote it lost to the Brexit Party in 2019, but failed to hang on to its existing vote share. True, Hartlepool was one of the most heavily Leave-voting constituencies in the 2016 referendum, but still...

The former MP for the seat, Peter Mandelson (who also knows something about spin), is unequivocal: Labour not only needs to turn a page, but open a new book.

He is surely right – but what will be in this new book? Probably not the Maastricht Treaty, or its descendants. Though the trends in the “red wall” seats were running against Labour for some years, two referendums really gave those slower movements a huge shove: the Scottish independence referendum of 2014, and the Brexit referendum of 2016.

Without its traditionally strong representation in working-class areas across Britain, Labour has had little chance of forming a government in Westminster; even the Corbynite surge in 2017 failed to stop the rot, and that was before Boris Johnson turned the Conservative Party into an unapologetically populist hardline Brexit movement.

The realignment has changed the Conservative Party itself, on balance for the better, and enabled it to claim that it represents the nation as a whole.

Hartlepool has become the latest emblem of that change, but it is far from the only one. By contrast, Labour remains as strong as ever, if not even more entrenched in its English conurbations, with substantial leads among the young, ex-Remainers, graduates and the professional classes.

For what it’s worth, Labour has colonised what is left of the Liberal Democrat old constituency, but it is losing some slivers of support to the Greens. Just as populist English nationalists have stolen much of Labour’s core vote in England, so have their SNP equivalents.

Labour has only ever won power by assembling a coalition of interests and voters, somehow appealing both to intellectuals and manual workers in all parts of the country. History suggests that it finds this task more troublesome than the Conservatives, who, in the democratic age, have always enjoyed some “patriotic” working-class support. Now the Tories seem to have an unbeatable coalition of voters, and a firm grip on power.

Must Labour lose? No. Well within living memory, in 1997, “New Labour” won a landslide majority based on building a remarkably broad base of support, one that kept it in power for the next 13 years. Tony Blair’s hat-trick of election wins was neither inevitable nor directly replicable in the conditions of the 2020s, and Mr Blair’s reputation within his own party would doom any such revivalist project from taking off – but the lessons of Labour’s last period of success need to be relearnt.

Whether Sir Keir Starmer is a Neo-Blairite or not, the party will need to follow the same path to recovery and power that it took in the 1990s and the 1960s.

The policies, though modernised, still need to be practical and believable, as well as popular; the presentational tone needs to be upbeat and confident; promises can only be made that can be kept; ideology should be avoided, dogma ditched, class warfare chucked, identity politics allied to obvious fairness; traditional symbols and values protected, and the economy placed front and centre of everything.

What they want in Hartlepool, and elsewhere, is not so hard to discern for those who care to listen to the people there. Above all, they want the kind of jobs, prospects and prosperity that they once enjoyed, and which is still the norm in much of the south.

When Mr Johnson talks about investment, building back better and levelling up, people respond to that; as they do when the government moves jobs north, establishes free ports, and boosts spending on infrastructure. That looks very much like delivery (even where it is a bit of a con).

They want better schools and hospitals, but not at the expense of provoking a crisis in the public finances and big tax hikes. They want their leaders to talk about expansion and growth and technology, not food banks and cuts and nuclear disarmament. A meritocratic opportunity society holds a timeless appeal, whoever is “selling” it; a welfare society has generally proved a less potent winner.

It was the kind of agenda that Tony Blair and Harold Wilson, the only two people to win elections for Labour in the last six decades, well understood. Mr Blair once remarked that his party will lose power if it gives up on “New Labour”. It might have been hubristic, but since 2007 it seems to have held true. The present Labour leader also needs to remind his party about the hard lessons of Hartlepool and history.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments