The long road to peace in Northern Ireland

After 25 years of The Troubles, the British and Irish governments finally gave the world reason for hope. It was a moment for David McKittrick to take stock

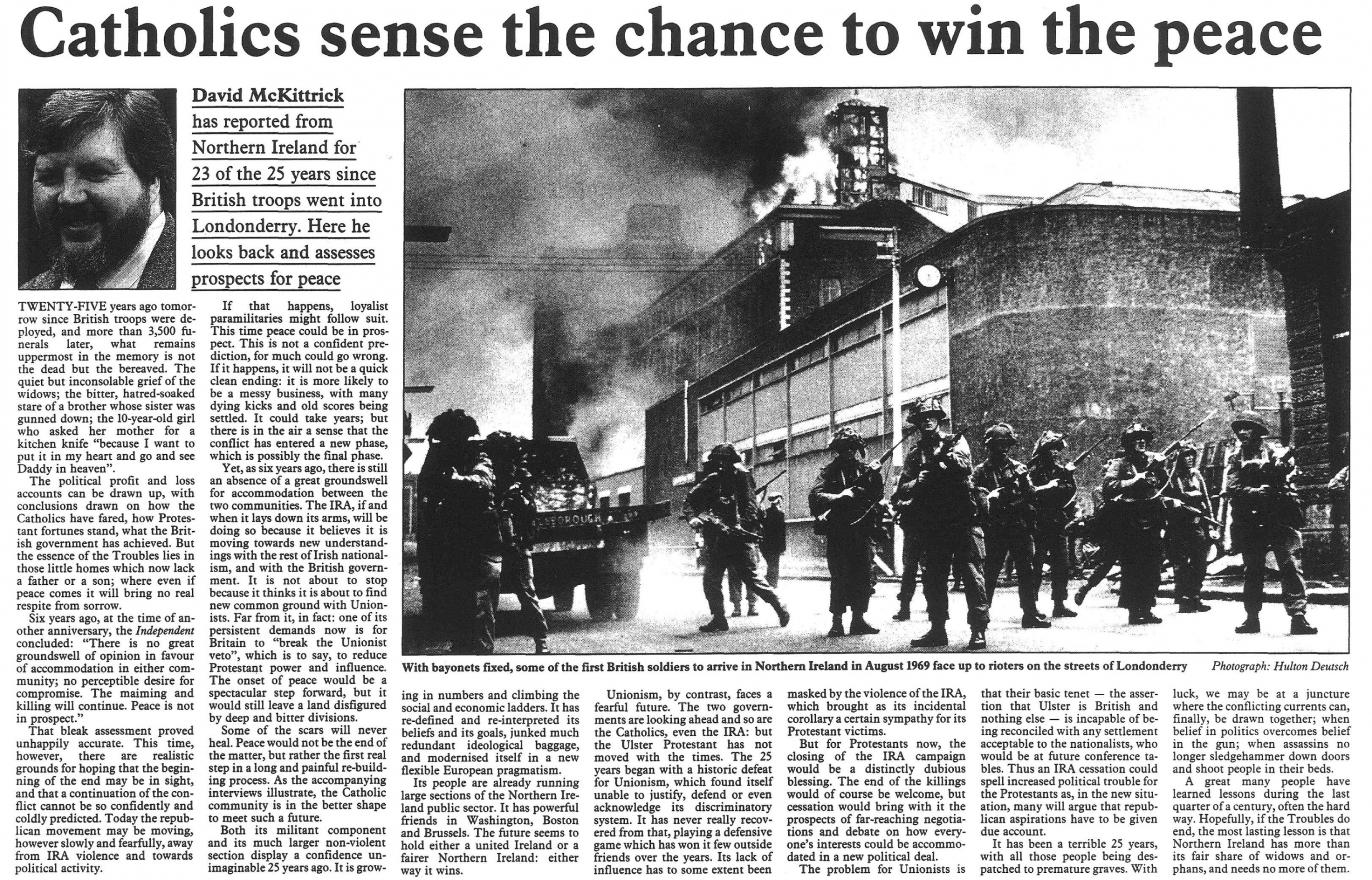

13 August 1994

Twenty-five years ago tomorrow since British troops were deployed, and more than 3,500 funerals later, what remains uppermost in the memory is not the dead but the bereaved. The quiet but inconsolable grief of the widows; the bitter, hatred-soaked stare of a brother whose sister was gunned down; the 10-year-old girl who asked her mother for a kitchen knife “because I want to put it in my heart and go and see Daddy in heaven”.

The political profit and loss accounts can be drawn up, with conclusions drawn on how the Catholics have fared, how Protestant fortunes stand, what the British government has achieved. But the essence of the Troubles lies in those little homes which now lack a father or a son; where even if peace comes it will bring no real respite from sorrow.

Six years ago, at the time of another anniversary, The Independent concluded: '“There is no great groundswell of opinion in favour of accommodation in either community; no perceptible desire for compromise. The maiming and killing will continue. Peace is not in prospect.”

That bleak assessment proved unhappily accurate. This time, however, there are realistic grounds for hoping that the beginning of the end may be in sight, and that a continuation of the conflict cannot be so confidently and coldly predicted. Today the republican movement may be moving, however slowly and fearfully, away from IRA violence and towards political activity.

If that happens, loyalist paramilitaries might follow suit. This time peace could be in prospect. This is not a confident prediction, for much could go wrong. If it happens, it will not be a quick clean ending: it is more likely to be a messy business, with many dying kicks and old scores being settled. It could take years; but there is in the air a sense that the conflict has entered a new phase, which is possibly the final phase.

Yet, as six years ago, there is still an absence of a great groundswell for accommodation between the two communities. The IRA, if and when it lays down its arms, will be doing so because it believes it is moving towards new understandings with the rest of Irish nationalism, and with the British government. It is not about to stop because it thinks it is about to find new common ground with Unionists. Far from it, in fact: one of its persistent demands now is for Britain to '“break the Unionist veto”, which is to say, to reduce Protestant power and influence. The onset of peace would be a spectacular step forward, but it would still leave a land disfigured by deep and bitter divisions.

Some of the scars will never heal. Peace would not be the end of the matter, but rather the first real step in a long and painful re-building process. As the accompanying interviews illustrate, the Catholic community is in the better shape to meet such a future.

Both its militant component and its much larger non-violent section display a confidence unimaginable 25 years ago. It is growing in numbers and climbing the social and economic ladders. It has re-defined and re-interpreted its beliefs and its goals, junked much redundant ideological baggage, and modernised itself in a new flexible European pragmatism.

Its people are already running large sections of the Northern Ireland public sector. It has powerful friends in Washington, Boston and Brussels. The future seems to hold either a united Ireland or a fairer Northern Ireland: either way it wins.

Unionism, by contrast, faces a fearful future. The two governments are looking ahead and so are the Catholics, even the IRA: but the Ulster Protestant has not moved with the times. The 25 years began with a historic defeat for Unionism, which found itself unable to justify, defend or even acknowledge its discriminatory system. It has never really recovered from that, playing a defensive game which has won it few outside friends over the years. Its lack of influence has to some extent been masked by the violence of the IRA, which brought as its incidental corollary a certain sympathy for its Protestant victims.

But for Protestants now, the closing of the IRA campaign would be a distinctly dubious blessing. The end of the killings would of course be welcome, but cessation would bring with it the prospects of far-reaching negotiations and debate on how everyone's interests could be accommodated in a new political deal.

The problem for Unionists is that their basic tenet – the assertion that Ulster is British and nothing else – is incapable of being reconciled with any settlement acceptable to the nationalists, who would be at future conference tables. Thus an IRA cessation could spell increased political trouble for the Protestants as, in the new situation, many will argue that republican aspirations have to be given due account.

It has been a terrible 25 years, with all those people being despatched to premature graves. With luck, we may be at a juncture where the conflicting currents can, finally, be drawn together; when belief in politics overcomes belief in the gun; when assassins no longer sledgehammer down doors and shoot people in their beds.

A great many people have learned lessons during the last quarter of a century, often the hard way. Hopefully, if the Troubles do end, the most lasting lesson is that Northern Ireland has more than its fair share of widows and orphans, and needs no more of them.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies