All about Eva Hesse

A collection of the sculptor Eva Hesse's diminutive, experimental works flirts with recognisable forms. It's life, but not quite as we know it, says Tom Lubbock

It's curious to think that just as Valerie Singleton was demonstrating to the viewers of Blue Peter the possibilities of toilet rolls, squeezy bottles and sticky-back plastic, the sculptor Eva Hesse was at work on her test pieces. It's not that their creations looked at all similar. Singleton's always resembled something; that was their point. Hesse's didn't, and that was almost theirs. But there was common ground. In both cases, an awareness of the act of making, and of the stuff involved, was vital to the work.

Eva Hesse is an artist's artist. Or perhaps she's an art critic's artist. (Or a curator's or an art historian's.) She was born in 1936 in Germany, fled to America as a child, and died in 1970 from a brain tumour. Since her death, her art-world reputation has become enormous. She's like one of the prophets. She expanded the vocabulary of sculpture's materials vastly. She devised numerous new ways in which a thing could stand for a body or a body process. Her work is not only an achievement but a continuing resource. The test pieces are in effect her 3D sketch-book.

Yet for the big public, the kind of audience who might go for Louise Bourgeois, she remains a pretty obscure figure. Hesse – one syllable – is still a great unknown. And the point of my Blue Peter comparison is not to mock, but to suggest that, in a way, you already enjoy the way she works, especially in these little ones. You enjoy the visible distance between medium and outcome. You enjoy the surprise, as everyday somethings are transformed. You enjoy – at a very basic level – small objects laid out on a flat table.

This show at Camden Arts Centre mainly consists of small objects on flat tables. It's hard to know how you display experimental things that weren't made to be displayed, that existed only in the studio. Do you attempt to reconstruct the studio itself with all its attendant mess and bits and pieces? Or do you take the things out of that context, and make them into clean and isolated specimens – specimens of creativity?

Both ways seem wrong. Both presentations lack the only thing that would make sense of the objects: the artist. But the artist is dead, the things survive, you're not going to hide them away or destroy them, you're interested, you have to do something. Eva Hesse: Studiowork takes the second way, and it's certainly the less wrong.

The term "Studiowork" is preferred to the previous "Test Pieces". It is coined by the exhibition's curator, Briony Fer, and – rarely amongst its genre – her accompanying book is a marvellous piece of writing and thinking. The old name told you that they were experiments, and definitely not artworks. The new one deliberately equivocates: kind of art, kind of not. That seems fine. It's Hesse's style generally. Her full-grown sculptures are themselves always equivocating about what kind of things they are. Their inconclusive nature is only an extension of these uncertain embryos.

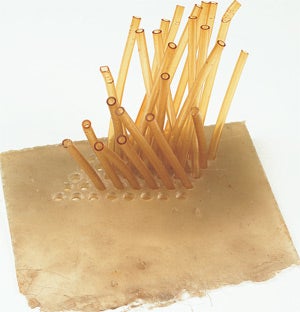

What are the studioworks like? You'll have noticed I haven't tried to describe anything yet. It's very hard. Giving look-alikes is easier, just as long as you understand that they're going to be misleading. So I could say that some of these objects seem to have been inspired by crammed ashtrays, and some by the spiky shells of conkers. One or two suggest a padded coat- hanger (but shaggy with threads, like a dress stitched up for alterations), or again a group of sprouting fronds, playing in an aquarium. You can find things that recall piles of blinis, or cake-trays, or a ball of rubber bands, or a well-used condom.

And there's a form that Hesse returns to often, and that was driving me mad with its elusive familiarity, until finally I realised that what it resembled is a tin can-and-string walkie-talkie. The likeness of course is remote. The can is half squashed. The tube goes the wrong way, emerging from its inside. And there's only one can involved. But the association sticks.

All these likenesses are remote. You might say that they're only a tribute to our unappeasable urge to give things names. But that urge is there, and art can't ask us to pretend that it isn't. Actually, Hesse's doesn't. It depends on it. Its effect largely involves our inclination to find resemblances, and her ability to both tempt and resist this inclination.

It's not that any particular likeness should flit across our minds before being rejected. Those are just my fairly subjective links, and some of the studioworks utterly defy real-world connections. You can only refer to some abstract physical quality: their grooves, entwinings, or slow bends.

But it's important that Hesse's works are never pure abstractions. It's important that likeness is always hovering around though being held off. These objects are like bits of the world that never actually happened but might have done. You can imagine coming across them in a glass case in some museum of mankind. They're very plausible anthropological impostors. And this points to Hesse's creative practice as a whole, where everything is almost, but not quite.

Or if you approach these objects not in terms of what they look like, but what they feel like, or how they seem to perform, again it's a matter of negatives. They're not tough and they're not tender. They're not active or passive. They're not male or female, nor alive or dead. They have nothing decisive to them, in any direction, not even towards floppiness. If they have a state, it's inert. If they have a gesture, it's awkward.

So Hesse is drawn to the least heroic materials – to rubber, to papier-mâché, to string. In the most beautiful display here, there are a dozen small pieces made of papier-mâché and stiffened cheesecloth. Their curved, hollowed shapes suggest simple boats, bowls, shells, a cupping action. They're set out widely spaced on a large table top. They sit thinly, crisply, lightly.

Are they embodiments of delicacy, of pin-point fragility? Are these boat-like, hand-like, shell-like forms emblems of care and salvation? Well, that's what they'd be in other hands. They'd be expressive, thematic. They'd be about something, and with feeling. (If Louise Bourgeois had made them, they'd be screaming with pathos.) But in Hesse's hands it's not quite like that – not quite. Their materials make them dumb. They squash and crumple. They don't have the pose or the poise. Whatever they might be, they are manqué.

Valerie Singleton, you feel, would not understand. In her creative world, things got finished. You could say with pride and good conscience: here's one I made earlier. In Eva Hesse's studio, good conscience went rather the other way. Her work, whether its being art or not, promotes an ethic of uncertainty, provisionality. And if you said there was perhaps a sentimentality in this attitude – a supersensitive reluctance to assert, define, conclude – I'd answer that there's actually a kind of shrug in the work, a what the hell, a why bother, that saves it from preciosity. It's even quite funny. Enjoy then.

Eva Hesse: Studiowork, Camden Arts Centre, London (Camdenarts centre.org; 020 7472 5500 ) to 7 March (closed Mondays) free

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments