National Poetry Day: The rise and rise of performance poetry

Performance poetry has come a long way since its alternative 1960s roots, but it still falls foul of traditionalists. On the eve of National Poetry Day, Peter Howarth looks at how the genre is standing up and being heard

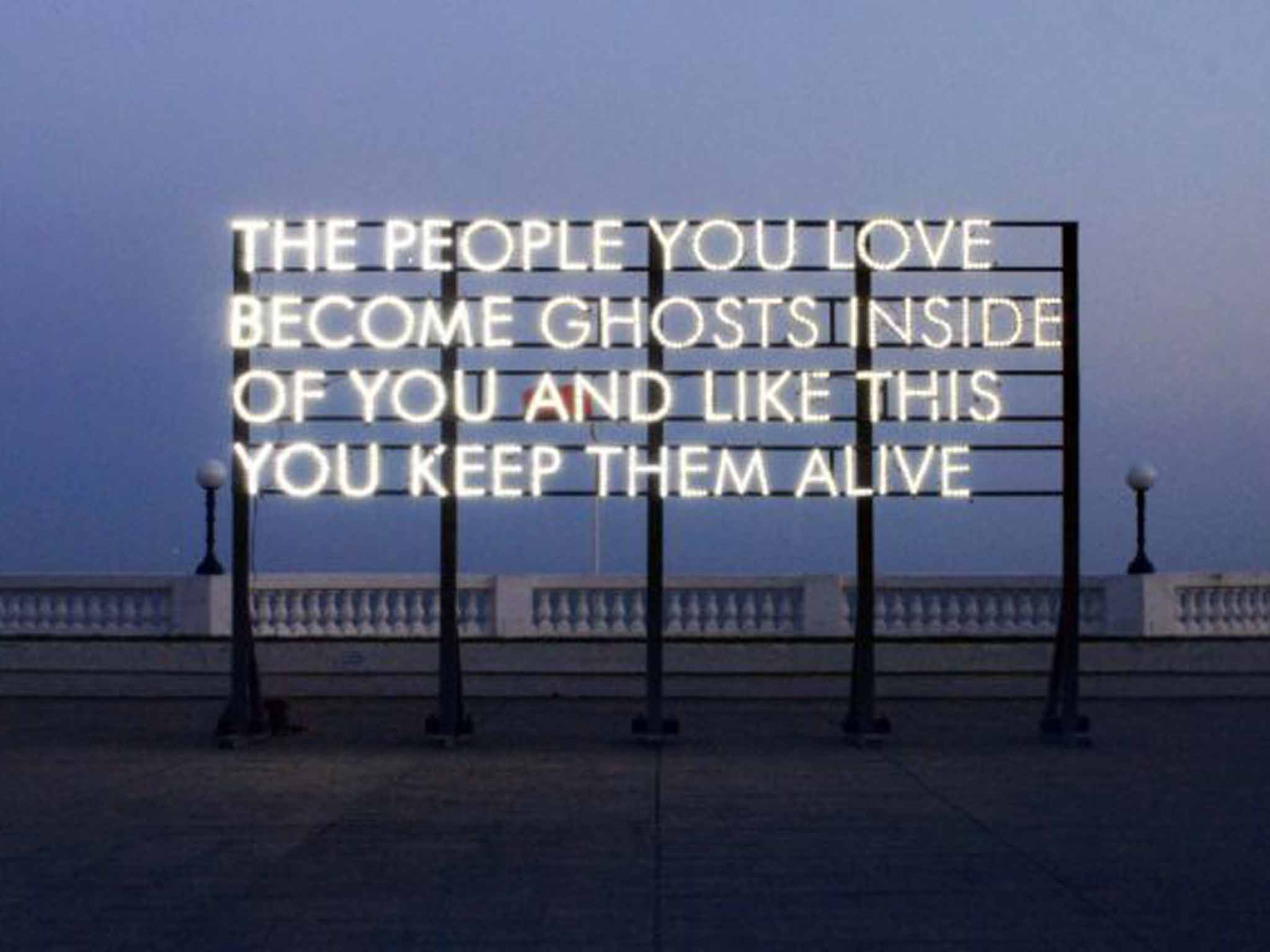

An electric sign on a twilit esplanade blazes with the words “The people you love / become ghosts inside / of you and like this / you keep them alive'. This eerie installation by Robert Montgomery will appear at National Poetry Day Live, an event curated by young poets at the Southbank Centre.

It sounds a bit flat in print, but the lights bring out dimensions not available on the page, burning on in the windy dark, like sad seaside illuminations.

That connection between word and place is Montgomery's stock in trade. He started by illegally pasting huge poster-poems over adverts for drivers to puzzle over in traffic. Nowadays, people get tattoos of his poems.

Installation poetry also makes Montgomery a canny choice for National Poetry Day. He produces written words that also perform, and in the world of poetry, that bridges a serious division between poets who write words for the page and those who aim for the stage.

The latter have long been dismissed as lightweight; too desperate for applause to say anything truthful.

“This fashion for poetry readings has led to a kind of poetry that you can understand first go: easy rhythms, easy emotions, easy syntax,” said Philip Larkin, perhaps unsurprisingly.

Yet poetry made for live performance now gathers audiences that page-poetry can only dream of.

When a younger generation of spoken-word artists such as Scroobius Pip or Kate Tempest fused dramatic monologues with the swagger of rap, they cracked the charts. There were poetry performance stages at Glastonbury, Bestival, and Reading this summer.

Perhaps for this very reason performance poetry continues to be disparaged by advocates of “proper” poetry. “I feel people are dismissing me when they say I'm a performance poet,” says Raymond Antrobus, who performed at Bestival but also organizes readings at Keats House, one of traditional poetry's hallowed spots. “I'm othered.”

It wasn't always like this. When microphone technology became good enough after the Second World War, poets read live regularly, and the novelty of an audience made a difference to the poems. There is a recording of T S Eliot doing all the different accents and machine-gun rhythms of his fragment Coriolan, delighting the audience, who had come to admire Eliot the public monument.

But Eliot has the last laugh. Coriolan is about how people become dictators by pleasing the crowds. Marianne Moore, meanwhile, used to rejig her poems to baffle fans who had come to hear the greatest hits: these poems, she was saying, are still in the process of being written.

But from the 1960s, performance poetry slowly became a genre in its own right. The avant-garde scenes in San Francisco and New York's Lower East Side cultivated improvisatory readings in protest against the neatly ordered pages of the college poets.

As civil rights failed to deliver and African-American poets allied with black cultural nationalism towards the end of the decade, the Last Poets produced the defiant rhythmic monologues that are key ancestors of rap.

Performance became the form for outsiders. Readings from the page, meanwhile, became so normal, and often so dreary, that poets forgot they were doing any kind of theatre at all. The two developed separate standards.

“Performance” meant the voice demanding a hearing. “Page” meant the layered and coolly distanced.

“Performance poetry is a style,” says Niall O'Sullivan, lecturer in performance poetry at London Metropolitan University and host, since 2005, of “Unplugged”, the Poetry Café's open mic night in Covent Garden. He adds: “It has greater application than just doing it live.”

That history has made the page-stage division stand for so much else; entitled vs. underclass, secure vs. precariat, white majority vs. multiracial mix. It's this difficult genesis that a new BBC documentary, Rhymes Rock & Revolution: The story of performance poetry, brings to life. Set to air on BBC4 this Monday, the documentary is part of the BBC's Contains Strong Language season, a series of radio and television programmes which aim to showcase new work, from established poets such as Simon Armitage to the lesser-known “punk poet” Thick Richard.

For most, the “punk poet” epithet conjures the image of John Cooper Clarke who, from the late 1970s – and still going strong – carved out a niche for performance poetry, appearing between bands and comics at club nights and on the festival circuit, reviving a tradition of poetry at the Music Hall.

Others – Linton Kwesi Johnson, for example – fused radical messages with dub reggae. But, O'Sullivan remembers, “performance poet” was a token term for “anyone alternative or black; a way to keep them in the corner”.

“You're good,” an audience member once told Antrobus, “but your work relies on performance.”

“I felt as if I'd been written off,” he adds. “Because it's performed, it somehow doesn't have the same lineage; the canon. As if performance is compensating for lack of education.” Actually, a sense of judgment typically runs right through spoken word events. The fear of the crowd – or the lure of YouTube fame – tempts novice performers to focus on themselves and to lose the most basic sense of drama. O'Sullivan teaches his students to make silences speak, neither reaching for quick laughs, nor deflecting judgment by writing verse “steeped in righteousness”. But spoken word can use judgment to dramatise pressures the poets are sensing elsewhere, for being poor or too young or the wrong colour.

Kate Tempest's characters speak with rhyme after rhyme in a way that's easy to parody. Heard live, though, the rhymes feel like strikes in Street Fighter. Rhymes that clinch too quickly let you feel what it's like to live where no one is listening for more than a second before cutting in. Still, call your event a poetry reading and only poetry fans will come.

Make it a one-person show, where the audience have an idea of the scenario, add sound and lights and it becomes theatre with a very interestingly written script.

That's what Julia Bird, the organiser of the 'Beginning to See the Light' show for National Poetry Day, does.

“I re-edit new collections to turn them into shows for people who would never think poetry was for them,” she says. “I talk to people making their first steps as a poetry audience. I go to where they are,” she adds, proudly.

She's done Daljit Nagra's re-told Ramayana and is currently behind Claire Pollard's Ovid's Heroines, which has been drawing audiences since 2013.

Doesn't that mean she has to tailor poetry to fit with theatre spaces and Arts Council priorities?

“Actually I like working with constraints,” she says. “It's like writing a sonnet.”

That capacity to see the theatre as a poetic structure also drives Penned in the Margins, a “publisher” that produces work for live tours, audio, phone apps, and only maybe for paper too.

“The page is one more recording device for us,” says director Tom Chivers.

Sunspots, a touring show which premiered at the London Literature Festival last week, mixes film, music and live reading from a book of poems about sunlight by Simon Barraclough.

The show immerses viewers in the sun's energy by sensitising them to the light in the film projector – there are scenes of city lights and mythological patterns – and the electricity that's powering the surround-sound.

The company is wary of advertising its work as just poetry: “It's too much of a fortified camp,” says Chivers.

But lights, sound and movement – even simply the suggestion of these, captured in an image of Montgomery's neon sign – allow poetry to do what it has always done: layer itself in the mind and magnetise the moment.

National Poetry Day Live takes place at the Southbank Centre, London, on Thursday 8 October between 1p and 6pm. Entry is free

Raymond Antrobus will read at 'Beginning to See the Light' and blogs at raymondantrobus.blogspot.co.uk

Niall O'Sullivan hosts the open mic night 'Unplugged!' each Tuesday at the Poetry Café, 22 Betterton St, London WC2H

For more information on Simon Barraclough's Sunspots go to pennedinthemargins.co.uk

Julia Bird curates Beginning to See the Light for National Poetry Day at the London Literature Festival, South Bank Centre, on Thursday

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies