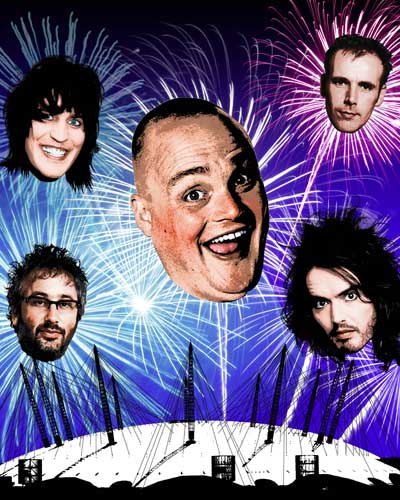

Big laughs: Why do we turn to stadium comedy whenever the economy becomes a sick joke?

Russell Brand and Al Murray are packing out London's 15,000-seat O2 Arena

Have you ever wondered what it must feel like to spend years honing a comedy act in front of small, indifferent audiences, before suddenly finding yourself performing variations on the same routine to tens of thousands of adoring fans at a time? Well, reading the American comedian Steve Martin's exquisitely well-written recent memoir Born Standing Up is the best way of finding out. "The laughs, rather than being the result of spontaneous combustion," explains Martin, "now seemed to roll in like waves created far out at sea."

That was America in the late 1970s, and the chance to experience this feeling was once an impossible dream for all bar the highest echelons of British comedic talent. But recently, playing before such huge crowds has started to look like an inevitable perk of your first appearance on 8 Out of 10 Cats.

Over the past couple of years there has been huge expansion in the audience for live comedy in Britain. London's O2 Arena (aka the successfully relaunched Millennium Dome) is becoming a regular stopping-off point for touring comedians. Russell Brand will play to a full house of 14,500 there on Friday night, followed next month by Al Murray as the Pub Landlord, with the Mighty Boosh, Lee Evans and the US comedian Chris Rock having all attracted multiple packed houses over the past year. And it's not only the A-listers who fancy their chances on the biggest stages of all. Performers who might once have hoped to supplement gigs on the club circuit with a successful tour of provincial theatres, followed by a run in the West End (old lags such as Frankie Boyle or Dara Ó Briain and relative newcomers such as Russell Howard and Michael McIntyre) are now contemplating itineraries that would once have been reserved for Billy Connolly and Eddie Izzard.

For those seeking an explanation for this unprecedented boom, the first port of call is the state of the nation's finances. Live comedy seems to be one of those comforting luxuries people are more inclined to find the money for when times are tight. How else to explain the fact that Britain's last two big live-comedy growth spurts – the foundation of the Comedy Store in the late 1970s, and Newman and Baddiel's famous gig at the 10,000-seat Wembley Arena in the early 1990s – also coincided with sharp economic downturns?

Jon Thoday's Avalon management company set up both Newman and Baddiel's 1993 arena apotheosis and the imminent O2 appearances by Al Murray, so he is ideally placed to compare then and now. "When Newman and Baddiel played Wembley, they did it on the back of the whole 'comedy is the new rock'n'roll' thing," Thoday recalls, "and no one else could have done it. The interesting thing now is that there are a lot of people who can."

By way of explanation, Thoday points to an unexpected quarter: he feels that the reluctance of TV networks to commission traditional comedy shows has heightened our appetite for live comedy. "If there had been six or seven artists with the power to command those kind of audiences in the early 1990s, they would have been massively pursued by the broadcasters and then been all over our screens. But as TV doesn't really have that many megastars any more – it's largely peopled by factual programmes – the hunger the public has for entertainment has pushed them to go out and look for it."

In this context, Michael McIntyre dissembling craftily on the Royal Variety Show, or Frankie Boyle being compellingly unpleasant on Mock the Week act as TV catnip for potential live consumers. In the aftermath of his self-imposed exile from the BBC, Russell Brand has generated an esprit de corps among audiences on his "Scandalous" tour (which climaxes at the O2 this week) by thanking the crowd "for coming to see me in a medium in which I am still allowed to flourish".

The scarcity value imparted by changes in televisual fashion and/or Daily Mail-instigated moral panics is not the only thing making stadium comedy a more practical proposition. Advances in amplification technology have also played their part. "When we did Newman and Baddiel at Wembley," Thoday admits, "we were absolutely terrified that the sound might not be any good. We had meetings about it every day for a week, and were still panicking on the night. But when Frank Skinner did three shows at Birmingham's NIA [the 6,500-seater National Indoor Arena] last year, we had one trial run and knew it was going to be fine."

The Mighty Boosh took their bespoke brand of dressing-up-box surrealism to the O2 for two nights late last year, and their manager, Caroline Chignell, points out an intriguing technical distinction between old-fashioned analogue and modern digital sound. "With analogue, the comedian's voice is like a wave that rolls out from the front of the stage, so they have to wait for the punch line to reach the back of the arena before everyone's got the joke. And that creates this kind of rolling laughter effect, which is incredibly distracting: it's almost like the delay on a transatlantic phone call. But with digital amplification, the signal goes out to everyone in the audience at exactly the same time."

For Murray, whose Pub Landlord will turn the 02 into the world's biggest snug bar for two nights next month, the prospect of playing to almost 30,000 people over two nights seems to hold few fears. However, staging his precisely observed parody of the prejudices of the Little Englander on a scale akin to the Nuremberg rallies raises particular problems in terms of how an audience of that size might respond.

"I have a whole chunk of punters who think I tell it like it is when no one else does," Murray admits cheerfully. "But I find ambivalence interesting. So I love the fact that I'll say something about the French being perverts, because they see sex as something to enjoy rather than snigger at, and half the crowd will be cheering and the other half will be laughing at it wryly. I think that makes the show better."

The huge increase in Murray's commercial clout over the past two years clearly owes a certain amount to the success of his ITV chat show: "I am getting this thing now where punters ask me, 'Do you do live stuff as well?' and I have to tell them I've been doing it for 15 years." But his long apprenticeship has been the ideal preparation for the new age of stadium comedy. "There are people who get a TV show which works, and then they can cash in and do some live stuff," says Thoday. (He won't say precisely who he's referring to here, but Ricky Gervais would probably be in the frame.) "But the great thing about people like Al or Russell Brand is that not only are they really talented, they've been out there on the circuit for ages, so now this opportunity has arisen they are perfectly placed to make the most of it."

Far from sacrificing intimacy in the leap from theatres to arenas, there's a sense that the atmosphere of live comedy shows has actually been enhanced by the step up in venue size. "I think it's to do with the hushed way in which we expect to experience shows in a theatre," Chignell explains. "When comedy audiences are sitting in the dark [in small clubs] being told to switch off their mobile phones, it sometimes doesn't quite work, whereas in an arena, that doesn't really happen."

Will Murray be doing anything special to take advantage of the "communal feel" he's expecting at next month's O2 performances? "I've had a bazooka made that fires packets of crisps 60 metres. I'm very excited about it, but it's a health and safety nightmare."

Russell Brand performs at the 02 Arena on Friday; Al Murray performs there on May 8-9; www.theO2.co.uk

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies