The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

American History X has a greater urgency than ever, 20 years on

The brutal black-and-white film has faith that the better angels of our nature will prevail, a feeling in increasingly short supply in modern America, writes Christopher Hooton

At the time of writing, 13 mail bombs have been intercepted on their way to prominent Democrats and left-leaning figures in the US. The man charged with dispatching them has a history of posting vitriolic, often threatening, tweets aimed at those on the other side of the political aisle. “He appears to be a partisan,” attorney general Jeff Sessions said of the suspect, which for many in this polarised climate is all the causality needed. He’s a right-wing extremist. Case closed.

To rewatch American History X this week, as it reaches its 20th anniversary, is to be reminded of the importance of trying to understand what drives people to commit heinous acts. Its story of a neo-Nazi’s attempts at reform has a new-found poignancy.

When the film was released on 30 October 1998, America was not wrestling with itself in the same way it is today. It’s not that the relationship between citizen and state was harmonious – April of that year actually saw the deadliest act of domestic terrorism in US history, the Oklahoma City bombing, when 168 people died after conspirators destroyed a federal building. But the country was not so divided, and the political centre ground was not so untenable. This was pre-9/11 America; Bill Clinton sat in the White House, and American History X’s subject was a fringe one. The drama was released to critical acclaim and with little fuss.

This would not be the case today. “Its willingness to take on ugly political realities gives it a substantial raison d’être,” The New York Times’ Janet Maslin wrote in her review of the film at the time. If anything, its ugly subject matter would now be reason for it not to exist.

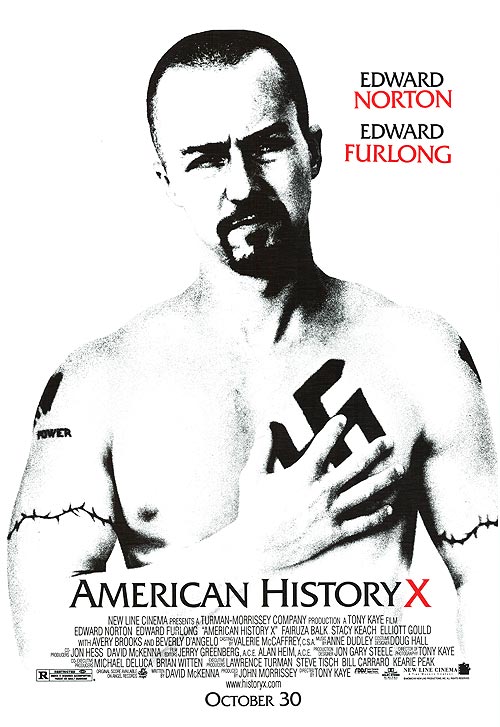

The poster (below) for the film is taken up solely by a portrait of a shirtless Derek, who places a hand over the swastika tattoo on his chest. It’s intentionally unclear whether he’s doing so with pride or in a bid to cover the hate symbol, but it’s a provocative image regardless. Had the poster been released in October of 2018 instead of 1998, it would have swiftly become a trending topic and in all likelihood led to boycotts. “Just what we need, another attempt to humanise the white supremacist,” would have been the main thrust of a thousand tweets, the shutters coming down long before anyone had actually seen the film.

The argument would have been made that there is no place for a film like American History X when Donald Trump is in the White House, a president who could – charitably – be described as only ever being a maximum of two degrees of separation away from a white supremacist. It’s inappropriate, critics would have argued, at a time when people waving Nazi flags marched in Charlottesville chanting “Jews will not replace us” and when – only just this weekend – 11 people were senselessly shot dead at a Pittsburgh synagogue. But the argument would have fallen apart upon first viewing of the film, which feels more essential now than it ever has. While American History X is at times prone to sentimentality, and its account of Derek’s redemption is a little linear and simplistic, the film is still successful in rallying our hope in humanity.

Viewed in 2018, certain facets of the movie stand out that didn’t before. When Derek’s little brother and protege Danny (Edward Furlong) turns in a paper at school entitled “My Mein Kampf”, his history teacher (Elliot Gould) is filled with the “shut it down” rhetoric of today. “This is dangerous,” he tells the African-American principal Dr Sweeney (Avery Brooks), calling on him to expel the pupil. “This goes too far.”

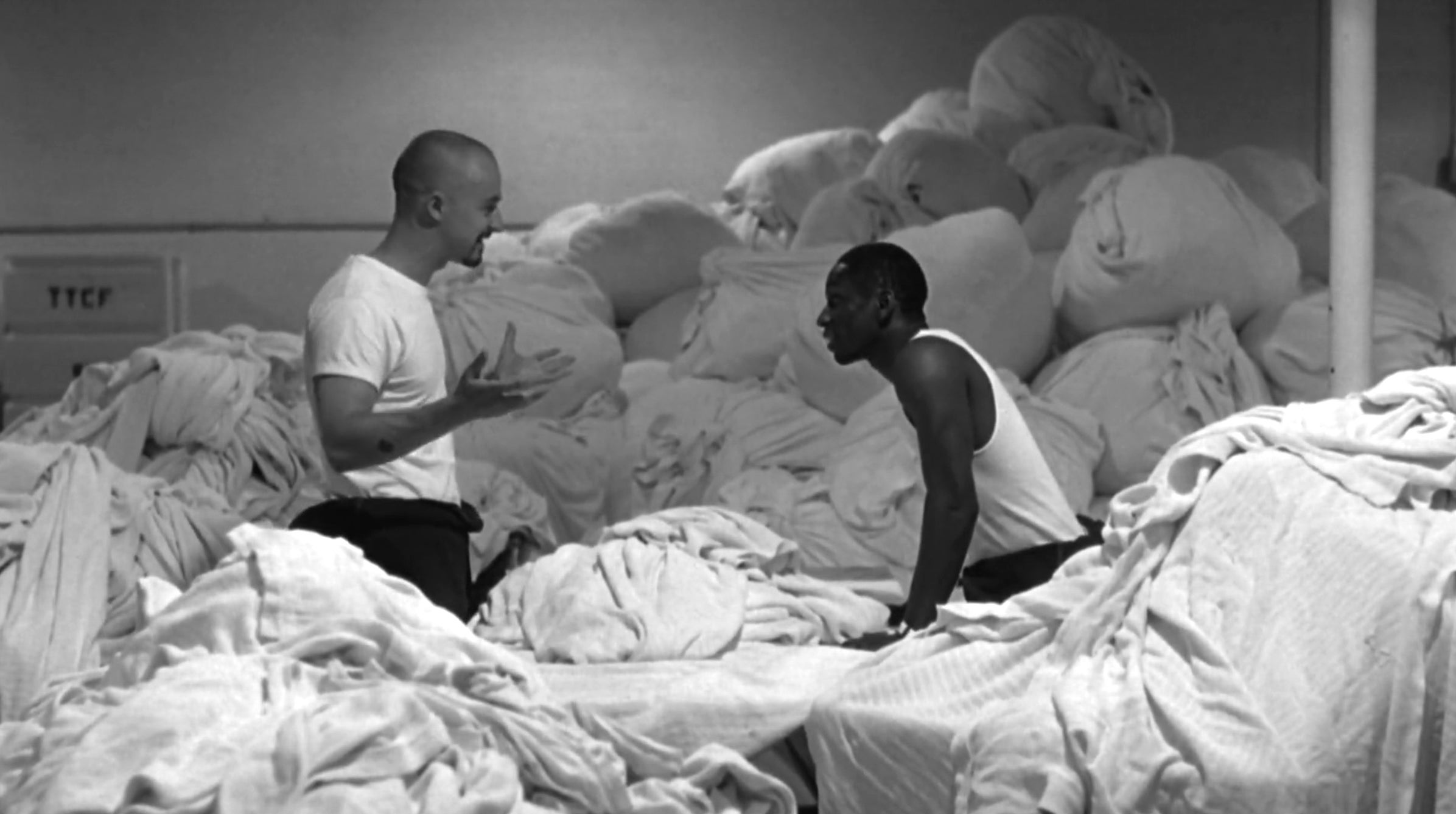

But Sweeney, in whom the film hopes the viewer will find a like-minded ally, retorts: “This racist propaganda, this ‘Mean Kampf’ psychobabble, he learned this nonsense and he can unlearn it too.” Crucially: “I will not give up on this child yet.”

Later, the white supremacist gang’s exploitative leader, Cameron (Stacy Keach), gloats when trying to persuade a reformed Derek back into the fold: “Wait till you see what we’ve done with the internet.” There’s no snappy comeback to this line, and it plays chillingly 20 years on, when the internet has become woven into our lives more than we ever might have imagined, and yet we still haven’t figured out an effective way to keep hate speech away from it.

Brutal though the film often is, it was too sappy for its director Tony Kaye, whose disapproval of his own film is now the stuff of Hollywood legend. Kaye turned in his cut on time and within budget, but the studio’s extensive notes led him to throw what he would later recognise as a “prima donna hissy fit”. Banned from the cutting room, he could only watch as Norton and parachuted-in film editor Jerry Greenberg created a new version. Their cut, 40 minutes longer than his “95-minute rough diamond”, left Kaye so dismayed that he punched a wall and broke his hand. He waged war on the studio, New Line Cinema, trying to prevent the film’s release and, when the execs would no longer speak to him (nor the Catholic priest, rabbi or Tibetan monk he insisted on bringing to negotiations), he spent $100,000 on ads in trade magazines aimed at them. Unsuccessful in blocking the film, he requested his credit be changed to “Humpty Dumpty”.

The film was, for Kaye, “crammed with shots of everyone crying in each other’s arms”. It’s a critique very much of its time – today it would be hard to imagine a harrowing, black-and-white film like this being given a budget of $20 million, and if it did the characters would be doing a lot more emoting.

In the early 2000s, American History X would be name checked by film buffs trying to demonstrate their sense of morals. That the film no longer sits comfortably in the collective consciousness as a pillar of virtue shows how much ideologies have shifted. In this incendiary era, forgiveness and rehabilitation aren’t now the core tenets of liberalism they once were, and have both become the subject of great controversy.

But, ultimately, as Sweeney’s patience pays off and Derek becomes a crucial ally in de-radicalising white supremacists, the film becomes more about prevention through understanding. That we must try and combat all forms of prejudice, and not let them prosper in societal exile, is something we can surely all agree on.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments