Analyse this: Will David Cronenberg get to heart of Sigmund Freud?

Cronenberg is the latest director to give Freud the movie treatment

"Talk?" "Yes, just talk," Carl Jung says to his patient, Sabina Spielrein, early in A Talking Cure, the Christopher Hampton play that David Cronenberg has made into a film, A Dangerous Method, which will premiere in Venice tomorrow. The play suggests that Jung not only treated Spielrein but subsequently had an affair with her. Their relationship marked a pivotal moment in the emergence of the new discipline of psychoanalysis, helping lead to a break between the 29-year-old Jung and his mentor, Sigmund Freud.

Cronenberg, the Canadian director of Crash, The Brood et al and the visual chronicler of body horror is not the obvious choice for a dialogue-driven costume drama set in turn-of-the-century Vienna. Nonetheless, as the producer Jeremy Thomas says of A Dangerous Method: "The film is like an incredible action movie with words. The references, whether or not you understand psychoanalysis, are so strong with dreams, impotence, desires, jealousy – all the things that are in the human psyche."

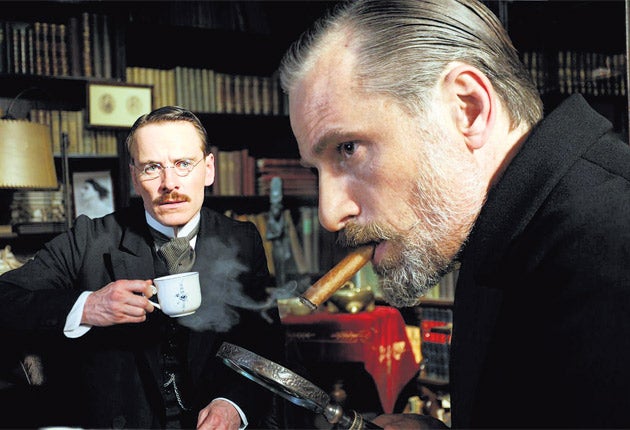

Sabina, played by Keira Knightley, is an immensely complex character: beaten by her father as a child, she is a masochist who finds sexual arousal in humiliation. The film also presents the vying of two alpha dogs, Jung (Michael Fassbender) and Freud (Viggo Mortensen).

The influence of Freud on cinema is so pervasive that it may come as a surprise that Freud himself has been portrayed on screen relatively infrequently. We have seen shrinks in countless comedies and dramas. We have seen many over-determined melodramas from the 1940s and 1950s that play like Freudian case studies, with heroines working through childhood traumas, overcoming kleptomania or amnesia or trying to decipher symbol-laden dreams. We have seen teen rebels with Oedipal desires. Even when there has been a backlash against Freud – "the great fraud", as he was dubbed by the psychologist Hans Eysenck – it hasn't worried Hollywood. Freud's work has provided very rich pickings for screenwriters.

Film-makers have testified to the influence of Freud. In a famous quote, Bernardo Bertolucci said that his experiences as a patient had enriched his creative life: "I found that I had in my camera an additional lens which was not Kodak, not Zeiss, but Freud." And psychoanalysts are a leitmotif in Woody Allen's work, even as he jokes relentlessly about them. In Annie Hall, Allen's Alvy Singer quips: "I was in analysis. I was suicidal. As a matter of fact, I would have killed myself, but I was in analysis with a strict Freudian and if you kill yourself they make you pay for the sessions you miss." The talking cure doesn't come cheap.

However, when it comes to portraying Freud himself, film-makers seem to take fright. Their most familiar response is to show him as a stern, patriarchal, cigar-smoking figure with a Father Christmas-like beard and, perhaps, a penchant for cocaine. They wheel him on for unlikely cameos in children's movies, comedies and sci-fi dramas. In Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure, Bill and Ted lasso him from the streets of Vienna; in Star Trek: The Next Generation, Freud pores over one of Data's nightmares. "You are experiencing a classic dismemberment dream," the doctor tells him. "Your mechanistic qualities are trying to reassert themselves over your human tendencies."

The founder of psychoanalysis has also been seen briefly in an episode of Frasier, and in The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. He pops up in I Dream Of Jeannie and Sabrina, The Teenage Witch. ("I don't know how to interpret dreams," Sabrina complains. "You don't but my old buddy Sigmund Freud does!" replies Salem the cat. Cue the appearance of the man from Vienna in the teenage girl's bedroom).

Freud was also beckoned by Dr Watson to treat Sherlock Holmes (and help cure him of his cocaine addiction) in Herbert Ross's 1976 comedy-drama, The Seven-Per-Cent-Solution. The conceit here was that Holmes and Freud were cut from the same cloth: just as the former could solve crimes through his astonishing powers of deduction, the latter could untangle the thickest knots in his patients' psyches through an equally clear-sighted and perceptive process of analysis.

As such cameos in populist film and TV fare suggest, Freud is an instantly recognisable figure who can be wheeled on to lend a little gravitas whenever dreams need unravelling. Specialist knowledge of his work isn't necessary. In movies, Freud's theories work far more easily than they do in real life. As he himself wrote: "It almost looks as if analysis were the third of those 'impossible' professions in which one can be sure beforehand of achieving unsatisfying results. The other two, which have been known much longer, are education and government."

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

If Freud's portrayal in pop culture is relentlessly superficial, the results when film-makers try to take him seriously are often worse. There have been a number of stolid costume dramas and biopics that have attempted to tell the Freud story. In 1962, John Huston's powers seemed to desert him when he directed Montgomery Clift as the Doctor in Freud: The Secret Passion.Huston had enlisted Jean-Paul Sartre to write the screenplay but the French philosopher handed in a draft, several hundred pages long, that was considered unfilmable.

Instead, Huston used a far more conventional treatment. As the critic Todd McCarthy noted, relations between Huston and Clift soured, devolving into "some sort of weird sadomasochistic game, with Huston allegedly baiting and torturing Clift and the actor turning increasingly to drink." Little trace of the tensions between star and director were evident, however, in a film that, by critical consensus, was too conventional and too straitlaced.

In 1984, the critics were not much kinder to a "lumbering" BBC drama, Freud, which starred David Suchet. Its problem, one critic wrote, was that it tried too hard "to relate the life to the work in a Freudian way", with sequences of Freud's dreams and flashbacks to his youth. There was also too much detail, "as though this were a kind of Open University course with tassels".

While the Beeb's Freud was considered too reverential, the following year Hugh Brody's Nineteen Nineteen was attacked for taking too many liberties. Two elderly people, Sophie Rubin, a Viennese Jew, and Alexander Sherbatov, a White Russian, compare notes about being analysed by Freud. Cue flashbacks, with the young Alexander (loosely based on Freud's patient Sergei Pankejeff, aka The Wolf Man) played by Colin Firth. Freud, voiced by Frank Finlay, was not seen on screen, thereby adding to his aloofness and mystique. The problem, in the eyes of some critics, was that the film was inaccurate: it speculated about a meeting that never took place. It is fine to take liberties with Freud in light-hearted comedies like Sabrina, The Teenage Witch but is clearly frowned upon when film-makers adopt a more earnest approach.

Cronenberg's A Dangerous Method will not be the only Freud-themed film screening in Venice. The British director Simon Pummell's Shock Head Soul explores the strange case of Daniel Paul Schreber (1842-1911), a top German lawyer who thought he was receiving messages from God via a "writing down" machine, and who wanted to become a woman and have a child. His memoirs of his psychosis inspired a famous essay by Freud (in which Freud speculated that Schreber's illness was a consequence of repressed homosexual desires.) Pummell's film is a "hybrid" work, combining documentary, fiction and animation – arguably this is an approach better suited to the complexity of the subject matter than a conventional narrative.

Whether these new films will make us see Freud is a new light is doubtful. What they might prove, though, is that the talking cure has as much dramatic potential as ever. You do not need to be Sabrina the Teenage Witch to relish the possibilities that it provides for probing deep into what drives the most closed and enigmatic characters.

'A Dangerous Method' and 'Shock Head Soul' premiere at the Venice Film Festival. 'A Dangerous Method' is released in the UK on 10 February 2012

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments