Mamoru Hosoda: ‘Too much is brushed off as a freedom of expression’

The anime film received a 14-minute standing ovation when it premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, now it’s coming to London, writes Michelle Ye Hee Lee

In her life in rural Japan, Suzu is a freckled and shy 17-year-old who is self-conscious about her looks and has lost her will to play music after her mum’s death.

But in the virtual world, known as “U”, she transforms into Belle, an enchanting, global, pop superstar with flowing pink hair and a mesmerising facial design that resembles freckles.

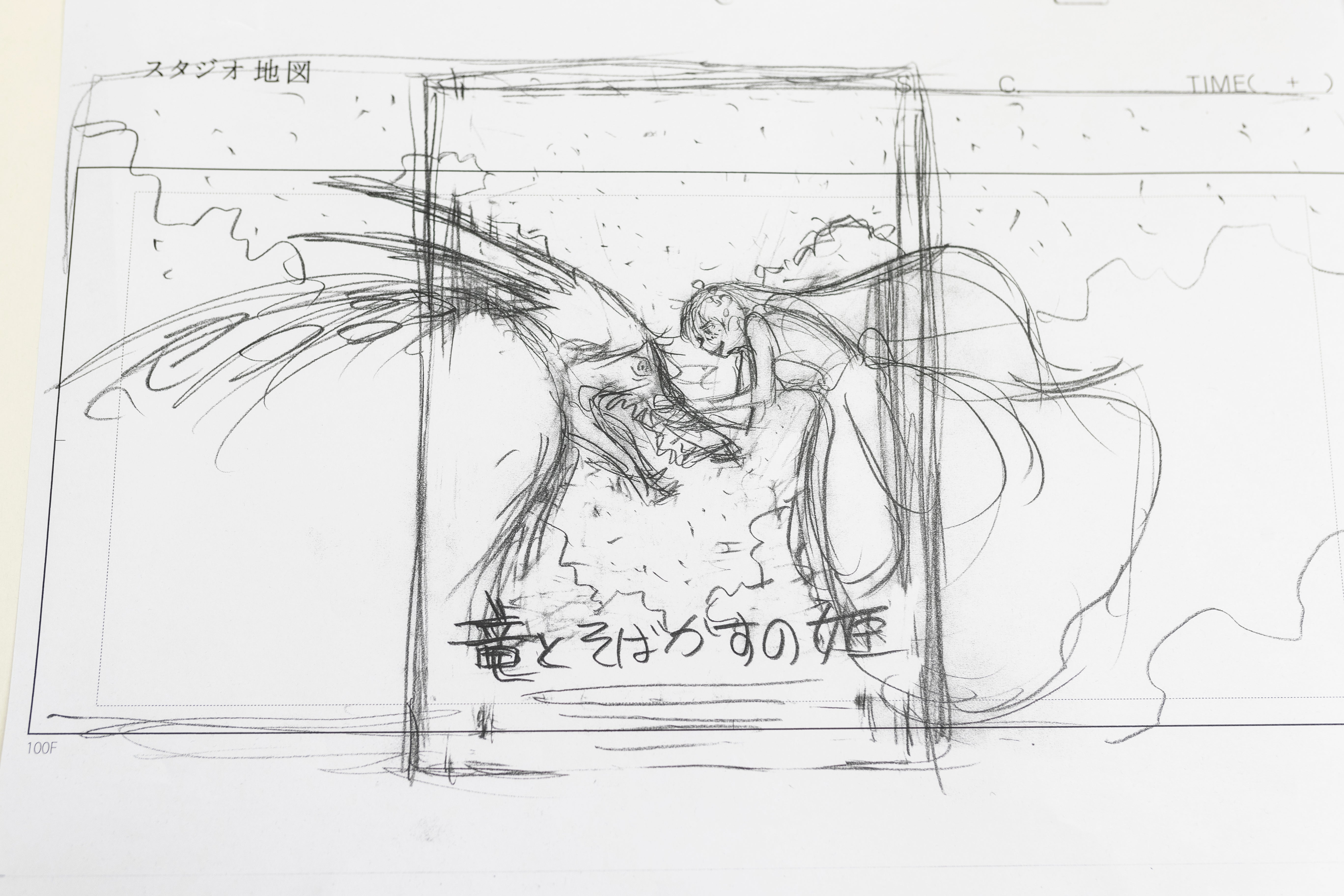

The animated film Belle – a hit in Japan that will make its UK debut at the BFI London Film Festival in October – also carries a bit of artistic rebellion.

The film’s message of female empowerment has gained attention for flipping the script on anime, Japan’s signature style of animated films and graphic novels that often portrays girls and women as weak, vacuous and hyper-sexualised.

The message has resonated in Japan as growing numbers of women call for change – most recently laid bare in a string of sexist comments by high-ranking Olympics officials that drew a fierce backlash.

“I feel that women characters in Japanese anime are often depicted through a lens of desire leading to their sexual exploitation and too much is brushed off as a freedom of expression,” the film’s director, Mamoru Hosoda, says at his Studio Chizu, his animation studio in a Tokyo suburb.

But problematic female representation in anime, especially in television shows aimed at males, has been a concern for gender equality advocates

From Disney princesses to Marvel superheroes, from anime to pop music, creators across genres are rethinking how to portray women and girls with agency and dignity and show that beauty does not mean having to be “perfect”. Global movements such as #MeToo have also underscored a sense of common purpose.

Hosoda said he hopes to draw attention to the ways that Japanese animation has shaped the public’s perceptions of women and girls and what it means to be beautiful and powerful.

“Such exploitation [has been] … justified with the notion that it’s happening in a fantasy world and not in reality. But I feel that, surely, such perceptions are connected and will influence our reality,” he says at his office, decorated with posters and figurines.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Japanese animation, which includes anime and manga, is among the country’s biggest cultural exports and has become popular on digital streaming.

But problematic female representation in anime, especially in television shows aimed at males, has been a concern for gender equality advocates. Such depictions are both overt – exaggerated breasts and barely clothed girls – and subtle, such as storylines in which girls are damsels in distress and secondary to boys.

In recent years, directors such as Hosoda have sought to challenge views in Japanese society that can devalue women, says Akiko Sugawa, a professor in gender and anime studies at Yokohama National University.

“Anime has the power to create and break gender stereotypes,” she says.

Sugawa says there is still much room for improvement, including the need for more women and LGBTQ anime directors.

“There are now more positive portrayals of LGBTQ characters, issues and works that pose questions about societal problems. And with the rise of more diverse directors and anime decision-makers, there’s hope for more change to come,” Sugawa says.

Belle is a modern twist on the Disney classic Beauty and the Beast. After her mother dies while trying to save a child from danger, Suzu struggles to fit in at school. She joins the virtual world “U” as Belle, a talented performer with eye-catching outfits who instantaneously gains billions of followers.

With the computer savvy of her female best friend and the emotional support of her late mother’s female friends, Suzu/Belle embarks on an adventure to help a mysterious beast. Along the way, Belle performs several songs that can now be heard throughout shopping districts of Tokyo. Since its release in July, Belle has become Japan’s third-highest-grossing film this year.

Hosoda seeks to give women and girls greater depth and humanity than is normally depicted in anime. Through Suzu/Belle, he juxtaposes the way that the inner beauty of Suzu and dynamism of Belle coexist in one person. For Suzu, an introverted teenager, her online persona is not just an imagination or an escape but rather a part of herself that she eventually grows into.

Hosoda says he wanted to give Belle more complexity, in the way the character of Beast in the Disney film was afforded that depth.

“Just like the beast having a duality, I wanted Belle to also have two sides and focus on how the two sides come to play, ultimately leading to her self-growth,” he says.

Hosoda received a 14-minute standing ovation when his film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in July. Belle has been replicated by “cosplayers”, who dress up as anime characters. The animated character Belle “performed” the film’s title song at the Fuji Rock Festival last month.

On social media, Japanese fans have raved about the positive message, stunning visuals and catchy tunes. “Those who are feeling difficulty in their lives, those who want to change but can’t, I hope they see this film. It really helps you take a step forward,” one fan tweeted.

Hosoda, 53, has long focused on the cyber world in his works, including the film versions of Digimon in1999 and 2000 and from his earliest feature films such as Summer Wars.

He has depicted women and girls as independent and strong-willed characters, including the 2018 Mirai, a story about a boy who lashes out after his sister is born but learns the importance of family bonds. The film earned Hosoda an Oscar nomination for best animated feature film.

But through Belle, Hosoda has delivered perhaps his most explicit message about female empowerment and the power of technology as a force for good. He says he was inspired by his five-year-old daughter, as he contemplates the future she faces.

“She is still in preschool and is quite introverted, so I imagined how she was going to survive once she gets on social media and begins having all sorts of online interactions,” he says.

Hosoda says he wanted to challenge the narratives warning against increasing reliance on the internet.

“For the younger generation, the norm will be to live in both worlds and that both worlds are their realities,” he says. “And the internet plays a huge role for them to raise their voice and go out into the world.”

Belle is scheduled for UK cinemas early next year.

© The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies