The films that improve with age

Many films now considered masterpieces had rocky opening weekends at the box office. Others deemed groundbreaking affairs on their first release have hardly been watched again. A new documentary focuses on the ups and downs of Brian De Palma's directorial career

Have you seen The Good Earth? No? Nor have I. When it was released in 1937, this adaptation of Pearl Buck’s novel about Chinese farmers struggling against drought and famine was considered one of the finest films Hollywood had ever produced, “a dignified, beautiful, and soberly dramatic production”, in the words of the New York Times. Its star Luise Rainer won the second of her consecutive Best Actress Oscars for her performance as “the pathetic slave girl ... modest and yet so indomitable”.

Eighty years on, the film is rarely, if ever, revived. The admiration of the critics and the Academy voters has done nothing to ensure its longevity. It is a forgotten movie. Rainer herself had long since passed out of public consciousness when she died aged 104 in London in late 2014.

There are many other films like The Good Earth that seemed important and groundbreaking affairs on their first release but have then been hardly watched again. They’ve quickly become dated. The popularity of their stars has waned.

The converse also applies. Movies are judged more than ever in knee-jerk fashion. A film that may have taken years to make is given a weekend to prove itself. If the reviews are lukewarm and the box office is disappointing, it won’t be able to hold onto its screens. Last year, there were 853 releases in British cinemas alone. With such a glut of product, there’s no chance to nurture a title and to allow the audience time to discover it. It is either love at first glance or the relationship is off for good.

The irony is that many films now considered masterpieces (and included in Sight & Sound magazine’s “Greatest Films Of All Time” list) had very rocky openings and only very slowly worked their way into the canon.

Jean Renoir’s country house drama La Regle Du Jeu (The Rules Of The Game), released in the summer of 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, was reviewed in astonishingly harsh fashion; attacked by audiences for being “unpatriotic” and eventually banned for being “negative” and “depressing”.

The story of how newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst took against Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941) has been told many times. At least, the film was released in its original form and didn’t suffer the indignity of its successor, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), which was previewed to a rowdy audience of young bucks and their girlfriends in Pomona, Los Angeles, on a Saturday night in 1942. They were expecting to see a musical and were baffled and bored by Welles’s account of the comeuppance of George Amberson Minafer. The studio reacted by cutting 50 minutes out of the film, mutilating it in the process. (This is one sad example of a film that was never given the chance to “improve” with age.)

Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), which displaced Citizen Kane at the very top of the most recent Sight & Sound poll, was given a surprisingly muted reception. Regarded today by a wide cross-section of critics and filmmakers as the greatest film ever made, it did only modest business at the box office by comparison with other Hitchcock films of the era. Audience and reviewers all seemed much to prefer its successor, North By Northwest (1959).

In Soviet Russia, Andrei Tarkovsky’s poetic masterpiece Mirror (1975), another film high up in the Sight & Sound poll, was dismissed by the authorities as “incomprehensible” and was hardly shown anywhere. Just as filmmakers in the west struggled with censors and Hollywood paymasters, those in the eastern bloc had to deal with the doctrine of socialist realism during the Stalin period. It was inevitable that a filmmaker as experimental and as lyrical as Tarkovsky would struggle to get his work made and shown.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Of course, the films haven’t changed. On one level, it is absurd to suggest that they have “improved” with age. Even when they are digitally remastered, the cuts are still in the same places and the dialogue and performances are just as they always were. The key difference isn’t in the movies but in how the audiences respond to them. Producer Jeremy Thomas recently talked about attending a screening of Nic Roeg’s Bad Timing (1980) at a London cinema. On its first release, the movie was attacked by its own distributors Rank as being as being a “sick” film made by sick people for sick audiences. In its account of the turbulent love affair between a psychiatrist (Art Garfunkel) and a much younger woman (Theresa Russell), it touches on obsessive love and even necrophilia. What seemed an outrageous exploitation picture in 1980 is received today as a consummately crafted and thematically very rich art house movie. The same level of admiration is also accorded to Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973) and to Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973), with which it was released on a double bill. Their distributor treated them as if they were low grade horror pictures but they are now regarded as being among the finest British films of their era.

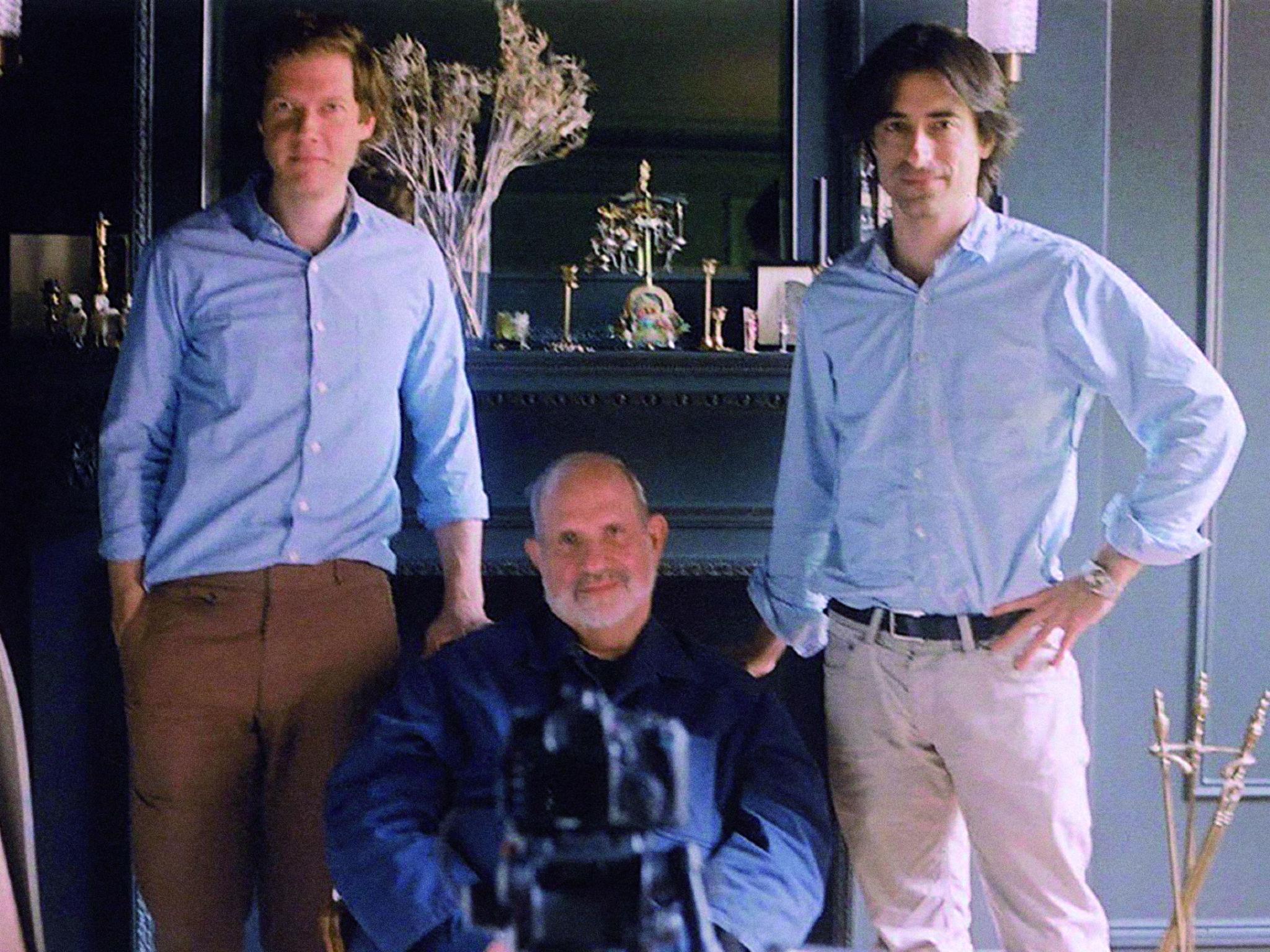

There are some poignant and sometimes comic moments in the new documentary De Palma, directed by Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow. In the film, Brian De Palma, now in his mid-seventies but still as belligerent as ever, reflects on the ups and downs of his directorial career. He sees himself as Hitchcock’s true heir. Some of his films have been received rapturously and have done huge box office (notably The Untouchables and Mission Impossible). Others have flopped disastrously – and he doesn’t think they should have done. You can blame the marketing and distribution strategy but the reef against which they’re crashed has always been what he calls “the fashion of the day”. His thriller Blow Out (1981), starring John Travolta, was given extremely enthusiastic reviews but the hitch was that he killed off the leading lady (Nancy Allen) in the final reel, thereby denying audiences the romantic ending they craved. They had come to see the film because of John Travolta, not because De Palma was directing it. The result was an unexpected box-office flop.

It’s not the films that improve with age. What actually happens to the lucky ones is that they’re seen in a new and fairer context. The hype and prejudice surrounding titles such as Heaven’s Gate on their initial release subsides and more careful attention is paid to them.

At the same time, certain hit movies begin to seem very much worse with the passage of even a small amount of time. Christopher Nolan has spoken of how dated and laughable 1990s digital visual effects appear to audiences today.

Directors such as De Palma can take consolation in the fact that their movies are being rediscovered and reassessed. What they can’t undo is the damage already suffered at the box office. A film’s reputation may rise but there’s a very little chance of turning it into a hit if it was pronounced dead on arrival first time round.

‘De Palma’ is released on Friday 23 September

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies