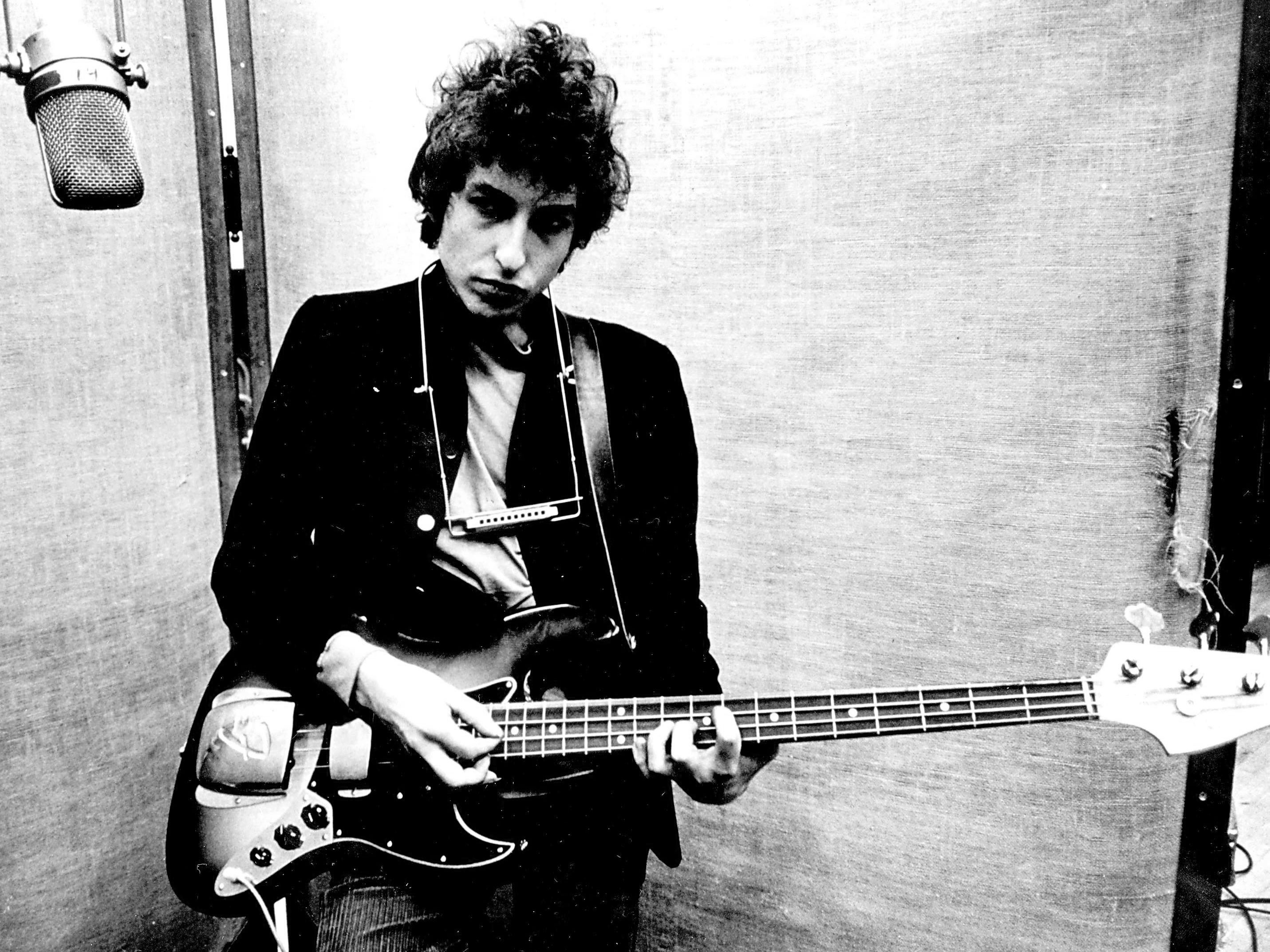

‘This is the blueprint’: Bob Dylan’s debut at 60

The artist’s self-titled first album barely sold any copies but contains the seeds of genius. Mark Beaumont talks to Frank Turner, Lia Metcalfe, Campbell Baum and Dylan biographer Howard Sounes about what it means to them

On 20 November 1961, a precocious 20-year-old kid from Minnesota rolls up to Columbia Studio A in New York City with an acoustic guitar and a bunch of punt money from a major record label. Over three short sessions, he records 17 raw and scratchy songs – mostly covers of songs he’d picked up in the folk clubs and coffee houses of Greenwich Village, or from listening to friends’ records – with little consideration for the etiquette or processes of recording; he’d roam off-mic, pop his “p”s and often refuse to do second takes because “I can’t see myself singing the same song twice in a row. That’s terrible.” Just two days and around $400 in studio costs later, he walks out with a makeshift debut album crammed with covers, destined to bomb on the record racks.

It’s a tale as old as the music industry itself. But this precocious 20-year-old was Bob Dylan, fresh from signing a five-year deal with Columbia Records’ John H Hammond but still lacking the confidence to pen many songs of his own. And the self-titled debut album he’d made – his first professional recordings, released 60 years ago today – would prove to be a historic, if inauspicious, prelude to a magnificent run of albums from 1963’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan to 1967’s John Wesley Harding that would reinvent folk, marry it to rock’n’roll and change the course of popular music forever.

Including just two original Dylan songs (“Talkin’ New York” and “Song to Woody”) among its plethora of covers of traditional folk and blues tracks – most notably “House of the Risin’ Sun”, with an arrangement “borrowed” from fellow New York folk scenester Dave Van Ronk – Bob Dylan has never been granted much canonical kudos. When Razorlight’s Johnny Borrell famously quipped “Dylan is making the chips, I’m drinking champagne”, it was this record he was comparing his own band’s debut with. But in recent years later generations of folk fans and budding Dylanologists have come around to the record, while the experts recognise its significance as the base ground from which one of the greatest ever creative leaps forward was executed. Here, contemporary musicians and experts discuss what Bob Dylan means to them.

Frank Turner, folk rocker who has reworked “Song to Woody” as “Song to Bob” live and on record

“It’s the record before Dylan hit his perfect streak, which lasted for about seven albums of utterly flawless material. You can hear the beginnings of what he was trying to do gathering on this record. A lot of it is basically trad folk, and he’s employing other people’s voices almost. He’s searching through a catalogue of voices to find his own one. Recording it so quickly and cheaply was quite punk. He was, at this period of history, still known as “Hammond’s Folly”. John Hammond had signed him, and he’d signed Aretha Franklin and all these other people. He spent quite a lot of money signing Dylan and this first record didn’t really go anywhere.

“To me, the pinnacle of the album is ‘Song to Woody’, which is the one song on this record which I think is as good as anything off Another Side… or The Times They Are a-Changin’. The other stuff on there, in a way it demonstrates his bona fides as a folk singer. Dylan’s hinterland is the fact that he was a total nerd. There are all these stories about when he was in Minnesota, stealing a copy of the Smithsonian Folk Collection from one of his neighbours, literally breaking into his house and nicking it. He was a student [of folk]… this was around the time when he was going to see Woody Guthrie in Bethesda in hospital at a point when nobody else was doing that. Woody Guthrie had been largely forgotten and was dying in a hospital just outside of New York and Bob Dylan went and befriended his wife, and then him. There wasn’t a long queue of people doing that, he was the only person doing it, which is where ‘Song to Woody’ comes from.

“He went on to write largely original material, as much as it was folk influenced, but this is the blueprint. It shows you where he was coming from and, with the benefit of hindsight, what he was heading towards. I think it’s a really important document. It’s the doctoral thesis before he went and wrote his first book, almost. It’s important that it demonstrates that what he went on to was grounded in the right kind of thing. He went on to change folk music. He went on to change a traditional genre, which is insane and has basically only ever been done once. It’s like Picasso’s childhood drawings. He could paint and draw in a photorealistic way, which means that his adventures into Cubism make much more sense because he could do everything. Similarly with Dylan, it’s him establishing his place as a proper folk singer before he went on to completely revolutionise folk music. It’s an important first step in his evolution as an artist.

“‘Song to Woody’ has been a huge song for me in my life. I covered it for a BBC session many years ago and it’s been in my set here and there. I changed the lyrics because he mentioned Sonny and Cisco [Sonny Terry was a blind blues musician, Cisco Houston a folk singer/songwriter; both collaborated with Guthrie] and all the rest of it and, if folk music is at least in part a passing of a baton, I thought that to cover it effectively it’d be cool to change the words to my generational version of what he was singing about.

“One of the things I find startling about Dylan is how fully formed he was when he burst onto the scene. It was almost like he wasn’t writing the songs, he was finding them in a chest in an attic or digging them out of a hole in the ground or something that had been left there by some previous civilisation. It’s so fully formed for somebody who was so young. This record is less fully formed [and] because it isn’t flawless, it almost makes the flawless run of albums slightly more bearable. It’s quite humanising and comforting. He’s a human being, and some of it’s a bit of a swing and a miss, but most of it is very, very good folk music.”

Lia Metcalfe, singer with Liverpool alt-rockers The Mysterines and long-standing Dylan fanatic; owns a self-inflicted Dylan tattoo on her wrist

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

“I did [the tattoo] myself when I was pretty drunk. I see him as the centre for me, where everything on my creative journey began. I started listening to him at such a young age, I must’ve been about 12, so he’s had a really big impact on my life. My uncle is a super big Dylan fan and he introduced me to Bob Dylan when I was a kid. The first record he gave me was ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ and after that was The Freewheelin’… Once I’d passed the test and started learning his songs and singing like Dylan, he then gave me the rest of the records and his debut album was in there. I’ve still got it now.

“I thought it was a great Dylan record. I find it really interesting when it’s referred to as a folk album because I think it’s quite blues – I put it in the same category as early Skip James and Muddy Waters, in a weird way. They’re great covers. His performance on it is so raw and for me the vocal on that debut record is some of his best work. It’s quite punk in a weird way. Back then that would’ve been considered quite heavy, how he was singing, he’s quite aggressive at some moments. And obviously the performance of ‘House of the Risin’ Sun’ is one of the best recordings of the song ever.

I learnt so much about myself growing up by listening to Dylan and still am

“I think it was Tom Waits who said that Bob Dylan is a planet to be explored and I’m still exploring that now. I learnt so much about myself growing up by listening to Dylan and still am. I think it should be taught in the education system.”

Campbell Baum, bassist with London experimental rockers Sorry, co-founder of Ra-Ra Rok Records and instigator of new folk collective Broadside Hacks, who perform and record DIY folk covers very much in the spirit of Bob Dylan. Their first compilation, Songs Without Authors (Vol. 1), featuring James Yorkston, Katy J Pearson, Junior Brother, ex-Goat Girl Naima Bock and others, was released last year

“During lockdown, when I started the whole idea of Broadside Hacks, it was interesting to me that a songwriter that is known for his own songwriting found his voice through playing all of these old songs. The fact that [Dylan] and Paul Simon came to England and started out playing around these folk clubs, playing traditional music, that definitely had an influence because like a lot of musicians that have been in this cycle of touring and gigging, when lockdown hit it was a time maybe to look at stuff from a different angle. Traditional music was something I’d listened to but it wasn’t something that I’d ever attempted to play or perform. But I thought that if it was enough of a foundation for them to start with, then there must be something in it that’s worth exploring.

“This new recording that we just put out [a cover of traditional folk song ‘Barbry Allen’], we basically did it in one day. We did everything in a few takes, partly because it was the only day that anyone could do. We wanted to capture the energy, the spirit that it had. I didn’t want to polish it too much; it’s not really arranged. I read something about Dylan, that he refused to do more than one or two takes on most of that first record. What’s great about [Bob Dylan] is it gives you context for the rest of what he did. It’s a snapshot of what he was doing at that particular time and not maybe fully realised in his head. It’s more him finding his voice and impersonating all of his influences, all of his idols.”

Howard Sounes, author of Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan

“It’s not a great record. The first great record Bob Dylan made is Freewheelin’… The first record is mostly a rag bag of stuff he’d borrowed and covered and copies, apart from ‘Song to Woody’, which is the only bit of brilliance on it. It’s a bit like Wes Anderson’s first film, Bottle Rocket, it’s the first film made by a great director but it’s not a great film. It sounds like Bob Dylan, it’s got his nasal voice and it’s full of energy and a romantic idea of America, but it’s like an audition piece, a student piece.

“This is one of the many oddball albums that he’s put out, it’s him trying to find his feet. What’s most interesting is, the week it was released he wrote ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’. ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ is one of the great songs of the 1960s, it’s historically important, it completely changed Bob Dylan’s career, it changed songwriting. The difference between Bob Dylan and Freewheelin’… is so dramatic. He goes from something that’s really not very impressive but slightly interesting to something that’s brilliant. That’s because he has the confidence to write his own songs. In 1962 it suddenly all comes together for him.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies