Sign up to Roisin O’Connor’s free weekly newsletter Now Hear This for the inside track on all things music Get our Now Hear This email for free

T here are things you don’t know you needed to see until they’re right in front of you. Among them is a letter sent to Lou Reed by Martin Scorsese, vouching for Johnny Depp during the casting of a film inspired by Reed’s song “Dirty Blvd”. It’s an artefact from a different time – a time when people still wrote letters, and advocated on behalf of Depp as an actor. It’s one of many items that tell a microscopic but cumulatively telling story of Lou Reed’s life, now accessible in a newly unveiled archive at the New York Public Library .

Two years ago, the library acquired all these boxes of materials gathered during Reed’s lifetime. It was Laurie Anderson, his widow, who approached the NYPL to ask whether it would be interested in conserving the items and, crucially, making them available to the public. Reed, who died in October 2013 of liver disease, already had a “de facto” archive, according to curator Jonathan Hiam. This was in the care of Sister Ray Enterprises, Reed’s publishing entity and touring company. After initial discussions, everyone agreed that the NYPL and Reed’s materials were a “perfect fit” for each other. Reed, Hiam points out, was “in many ways the consummate New Yorker”, and wouldn’t it make sense for his story to live on in the city that so inspired it?

That’s how the boxes came to arrive, full of items ready to be sorted through, inventoried, and prepared for public consumption. There were two waves: one for Reed’s papers and one for audio and electronic records. His materials were already “fairly organised”, as Hiam remembers it, but they still needed to be vetted, rehoused for long-term conservation, registered in a finding aid (a long list in which each document is assigned a reference number, to help library users request them), and digitised. The archive opened in March, the month of what would have been Reed’s 77th birthday.

It’s a little unsettling to find Reed the rock star, who sang “Perfect Day”, “Satellite of Love” and “Walk on the Wild Side”, who got his start in the Velvet Underground, befriended Andy Warhol, and gave us the Berlin album, reduced to an assortment of bric-a-brac. Still, rock star or not, Reed acquired stacks of paper over his life, just like the rest of us, and everything now gets to be organised as part of a larger project.

It begs the question: was Reed aware that these documents – legal forms, breakfast instructions issued to staff, an ironic “Ten Commandments for a Rock Band” list – would one day come together to paint a broader picture of his life? According to Hiam, Reed wasn’t exactly the type to hold on to old drafts. It’s hard to tell exactly how much energy, if any, he dedicated to his own past.

Show all 40 1 /40The 40 best albums to listen to before you die The 40 best albums to listen to before you die The Velvet Underground & Nico (1967), The Velvet Underground It was Andy Warhol who wanted Lou Reed and John Cale to let his beautiful new friend Nico sing with their avant-garde rock band. Truthfully, though, Victor Frankenstein himself couldn’t have sewed together a creature out of more mismatched body parts than this album. It starts with a child’s glockenspiel and ends in deafening feedback, noise, and distortion. Side one track one, “Sunday Morning”, is a wistful ballad fit for a cool European chanteuse sung by a surly Brooklynite. “Venus in Furs” is a jangling, jagged-edge drone about a sex whipping not given lightly. “I’ll Be Your Mirror” is a love song. European Son is rock’n’roll turned sonic shockwave. That’s before you even get on to the song about buying and shooting heroin that David Bowie heard on a test pressing and called “the future of music”. Half a century on, all you have to do is put electricity through The Velvet Underground & Nico to realise that he was right. Chris Harvey

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You (1967), Aretha Franklin When Jerry Wexler signed the daughter of a violent, philandering preacher to Atlantic records, he "took her to church, sat her down at the piano, and let her be herself". The Queen of Soul gave herself the same space. You can hear her listening to the band, biding her time before firing up her voice to demand R-E-S-P-E-C-T 50 years before the #MeToo movement. Helen Brown

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Master of Puppets (1986), Metallica Despite not featuring any singles, Metallica’s third album was the UK rock radio breakthrough they’d been looking for. In 1986, they released one of the best metal records of all time, which dealt with the potency and very nature of control, meshing beauty and raw human ugliness together on tracks like “Damage Inc” and “Orion”. This album is about storytelling – the medieval-influenced guitar picks on opener “Battery” should be enough to tell you that. Although that was really the only medieval imagery they conjured up – they ripped Dungeons & Dragons clichés out of the lyrics and replaced them with the apocalypse, with bassist Cliff Burton, drummer Lars Ulrich, guitarist Kirk Hammett and singer/rhythm guitarist James Hetfield serving as the four horsemen. Roisin O’Connor

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Remain in Light (1980), Talking Heads “Facts are simple and facts are straight / Facts are lazy and facts are late…” sang David Byrne, submerging personal and planetary anxieties about fake news and conspicuous consumption in dense, layers and loops of Afrobeat-indebted funk. Propulsive polyrhythms drive against the lyrical pleas for us to stop and take stock. Same as it ever was. HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Catch a Fire (Jamaican version) (1973), Bob Marley and the Wailers The album that carried reggae music to the four corners of the Earth and made Bob Marley an international superstar also set the political tone for many artists to follow. Marley sang of life “where the living is hardest” in “Concrete Jungle” and looked back to Jamaica’s ignoble slaving past – “No chains around my feet but I’m not free”. He packed the album with beautiful melodic numbers, such as “High Tide and Low Tide”, and rhythmic dance tracks like “Kinky Reggae”. Released outside of Jamaica by Island Records with guitar overdubs and ornamentation, the original Jamaican version is a stripped-down masterpiece. CH

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Revolver (1966), The Beatles An unprecedented 220 hours of studio experimentation saw George Martin and The Beatles looping, speeding, slowing and spooling tapes backwards to create a terrifically trippy new sound. The mournful enigma of McCartney’s “For No One” and the psychedelia of Lennon’s “Tomorrow Never Knows” and “She Said, She Said” can still leave you standing hypnotised over the spinning vinyl, wondering if the music is coming out or being sucked back in. HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Like a Prayer (1989), Madonna It may be the most “serious” album she’s ever made, yet Like a Prayer is still Madonna at her most accessible – pulling no punches in topics from religion to the dissolution of her marriage. In 1989, Madonna’s personal life was tabloid fodder: a tumultuous marriage to actor Sean Penn finally ended in divorce, and she was causing controversy with the “Like a Prayer” video and its burning crosses. On the gospel abandon of the title track, she takes the listener’s breath away with her sheer ambition. Where her past records had been reflections of the modern music that influenced her – Like a Prayer saw her pay homage to bands like Sly & the Family Stone, and Simon & Garfunkel. The album was also about an artist taking control over her own narrative, after releasing records that asked the audience – and the press – to like her. RO

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Led Zeppelin IV (1971), Led Zeppelin Millennials coming at this album can end up feeling like the guy who saw Hamlet and complained it was all quotations. Jimmy Page’s juggernaut riffs and Robert Plant’s hedonistic wails set the bench mark for all subsequent heavy, hedonistic rock. But it’s worth playing the whole thing to experience the full mystic, monolithic ritual of the thing. Stairway? Undeniable. HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die The Best of the Shangri-Las (1996), The Shangri-Las Oh no. Oh no. Oh no no no no no, no one ever did teen heartbreak quite like the Shangri-Las. Long before the Spice Girls packaged attitude for popular consumption, songwriter Ellie Greenwich was having trouble with a group of teenagers who had grown up in a tough part of Queen’s – “with their gestures, and language, and chewing the gum and the stockings ripped up their legs”. But the Shangri-Las sang with an ardour that was so streetwise, passionate and raw that it still reaches across more than half a century without losing any of its power. "Leader of the Pack" (co-written by Greenwich) may be their best-known song, but they were never a novelty act. This compilation captures them at their early Sixties peak. CH

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972), David Bowie Flamboyance, excess, eccentricity – this is the breakthrough album that asserted Bowie as glam rock’s new icon, surpassing T Rex. He may have come to rue his Ziggy Stardust character, but with it, Bowie transcended artists seeking authenticity via more mundane means. It was his most ambitious album – musically and thematically – that, like Prince, saw him unite his greatest strengths from previous works and pull off one of the great rock and roll albums without losing his sense of humour, or the wish to continue entertaining his fans. “I’m out to bloody entertain, not just get up onstage and knock out a few songs,” he declared. “I’m the last person to pretend I’m a radio. I’d rather go out and be a colour television set.” RO

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Unknown Pleasures (1979), Joy Division In their brief career, ended by the suicide of 23-year-old singer Ian Curtis, Joy Division created two candidates for the best album by anyone ever. Closer may be a final flowering, but Unknown Pleasures is more tonally consistent, utterly unlike anything before or since. The mood is an all-pervading ink-black darkness, but there is a spiritual force coming out of the grooves that is so far beyond pop or rock, it feels almost Dostoevskyan. There are classic songs – "Disorder", "She’s Lost Control" and "New Dawn Fades" – and for those who’d swap every note Eric Clapton ever played for one of Peter Hook’s basslines, the sequence at 4:20 on "I Remember Nothing" is perhaps the single most thrilling moment in the entire Joy Division catalogue. CH

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Hejira (1976), Joni Mitchell Though her 1971 album, Blue, is usually chosen for these kinds of lists, Mitchell surpassed its silvery, heartbroken folk five years later with a record that found her confidently questioning its culturally conditioned expectations of womanhood. Against an ambiguous, jazzy landscape, her deepening, difficult voice weighs romance and domesticity against the adventure of “strange pillows” and solitude. HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Body Talk (2010), Robyn The answer to whether Robyn could follow up the brilliance of her self-titled 2005 album came in a burst of releases in 2010, the EPs Body Talk Pt 1, Pt 2 and Pt3, and this 15-track effort, essentially a compilation album. It includes different versions of some tracks, such as the non-acoustic version of “Hang With Me” (and we can argue all night about that one), but leaves well alone when it comes to the single greatest electronic dance track since “I Feel Love”, “Dancing On My Own”. Body Talk is simply jammed with great songs. CH

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Off The Wall (1979), Michael Jackson “I will study and look back on the whole world of entertainment and perfect it,” wrote Jackson as he turned 21 and shook off his cute, controlled child-star imagery to release his jubilant, fourth solo album. Produced by Quincy Jones, the sophisticated disco funk nails the balance between tight, tendon-twanging grooves and liberated euphoria. Glitter ball magic. HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Illmatic (1994), Nas How good can rap get? This good. There are albums where the myth can transcend the music – not on Illmatic, where Nas vaulted himself into the ranks of the greatest MCs in 1994, with an album that countless artists since have tried – and failed – to emulate. Enlisting the hottest producers around – Pete Rock, DJ Premier, Q-Tip, L.E.S and Large Professor – was a move that Complex blamed for “ruining hip hop”, while still praising Nas’s record, because it had a lasting impact on the use of multiple producers on rap albums. Nas used the sounds of the densely-populated New York streets he grew up on. You hear the rattle of the steel train that opens the record, along with the cassette tape hissing the verse from a teenage Nasty Nas on Main Source’s 1991 track “Live at the BBQ”: ‘When I was 12, I went to Hell for snuffing Jesus.” RO

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Trans-Europe Express (1977), Kraftwerk This is the album that changes everything. The synthesised sounds coming out of Kraftwerk’s Kling-Klang studios had already become pure and beautiful on 1975’s Radio-Activity, but on Trans-Europe Express, their sophistication subtly shifts all future possibilities. The familiar quality of human sweetness and melancholy in Ralf Hutter’s voice is subsumed into the machine as rhythms interlock and bloom in side two’s mini-symphony that begins with the title track. Released four months before Giorgio Moroder’s "I Feel Love", Trans-Europe Express influenced everything from hip-hop to techno. All electronic dance music starts here. CH

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Kind of Blue (1959), Miles Davis With the sketches of melody only written down hours before recording, the world’s best-selling jazz record still feels spontaneous and unpredictable. Davis’s friend George Russell once explained that the secret of its tonal jazz was to use every note in a scale “without having to meet the deadline of a particular chord”. Kind of Blue is unrepeatably cool. HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Astral Weeks (1968), Van Morrison “If I ventured in the slipstream, between the viaducts of your dream…” To enter this musical cathedral, where folk, jazz and blue-eyed soul meet is always to feel a sense of awe. Recorded in just two eight-hour sessions, in which Morrison first played the songs to the assembled musicians then told them to do their own thing, Astral Weeks still feels as if it was made yesterday. Morrison’s stream-of-consciousness lyrics within the richness of the acoustic setting – double bass, classical guitar and flute – make this as emotionally affecting an album as any in rock and pop. CH

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die West Side Story Soundtrack (1961) “Life is all right in America / If you're all white in America” yelp the immigrants in this passionate and political musical relocating of Romeo and Juliet to Fifites New York. Leonard Bernstein’s sophisticated score is a melting pot of pop, classical and Latin music; Stephen Sondheim’s lyrics sharp as a flick knife. An unanswered prayer for a united and forgiving USA. HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Sign o' the Times (1987), Prince Sign o’ the Times is Prince’s magnum opus from a catalogue of masterworks – a double album spanning funk, rock, R&B and most essentially, soul. It is the greatest articulation of his alchemic experiments with musical fusion – the sum of several projects Prince was working on during his most creatively fruitful year. On Sign o’ the Times, the bass is king – Prince cemented his guitar god status on Purple Rain. There are tracks that drip with sex, and love songs like “Adore”, which remains one of the greatest of all time. Stitched together with the utmost care, as if he were writing a play with a beginning, a middle and an end, the album is a landmark in both pop and in art. RO

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Pet Sounds (1966), The Beach Boys Caught in the psychological undertow of family trauma and all those commercial surf songs, 23-year-old Brian Wilson had a panic attack and retreated to the studio to write this dreamlike series of songs whose structural tides washed them way beyond the preppy formulas of drugstore jukeboxes. Notes pinged from vibraphones and coke cans gleam in the strange, sad waves of bittersweet melody. HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Ys (2006), Joanna Newsom Weave a circle round her thrice… Joanna Newsom is dismissed by some as kookily faux-naif, but her second album, before she trained out the childlike quality from her voice, may be the most enchanted record ever made. At times, she sounds other-worldly, sitting at her harp, singing to herself of sassafras and Sisyphus, but then a phrase will carry you off suddenly to the heart’s depths – “Still, my dear, I’d have walked you to the edge of the water”. Ys’s pleasures are not simple or immediate. Newsom’s unusual song structures, with their fragmented melodies, and strange and beautiful orchestral arrangements by 63-year-old Van Dyke Parks, take time to work their magic. But once you’re bewitched, Ys’s spell never wears off. CH

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (1988), Public Enemy Public Enemy’s second album is hip-hop’s game-changing moment, where a new musical form that arrived fully born after years of development away from meddling outsiders found its radical voice. It Takes a Nation of Millions… is still one of the most powerful, provocative albums ever made, “Here is a land that never gave a damn / About a brother like me,” raps Chuck D on “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos”. Producer Hank Shocklee creates a hard-edged sound from samples that pay homage to soul greats such as James Brown and Isaac Hayes, and Flavor Flav gives it an unmistakeable zest. CH

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Dark Side of the Moon (1973), Pink Floyd It’s easy to knock these white, male, middle-class proggers, with their spaceship full of technology and their monolithic ambitions. But the walloping drums, operatic howls and “quiet desperation” of this concept album about the various forms of madness still resonates with the unbalanced, overwhelmed and alienated parts of us all. Play loud, alone and after dark. HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (1998), Lauryn Hill Lauryn Hill raised the game for an entire genre with this immense and groundbreaking work. Flipping between two tones – sharp and cold, and sensual and smoky – the former Fugees member stepped out from rap’s misogynist status quo and drew an audience outside of hip hop thanks to her melding of soul, reggae and R&B, and the recruitment of the likes of Mary J Blige and D’Angelo. Its sonic appeal has a lot to do with the lo-fi production and warm instrumentation, often comprised of a low thrumming bass, tight snares and doo-wop harmonies. But Hill’s reggae influences are what drive the album’s spirit: preaching love and peace but also speaking out against unrighteous oppression. Even today, it’s one of the most uplifting and inspiring records around. RO

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Histoire de Melody Nelson (1971), Serge Gainsbourg The great French singer-songwriter provocateur probably wouldn’t get too many takers today for a concept album about a tender love between his middle-aged self and a teenage girl he knocks off her bicycle in his Rolls-Royce. But, musically, this cult album is sublime, an extraordinary collision of funk bass, spoken-word lyrics and Jean-Claude Vannier’s heavenly string arrangements. “Ballade de Melody Nelson”, sung by Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin, is one of his most sublimely gorgeous songs. CH

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die In My Own Time (1971), Karen Dalton There’s nothing contrived about Karen Dalton’s ability to flip out the guts of familiar songs and give them a dry, cracked folk-blues twist. Expanding the emotional and narrative boundaries of songs like Percy Sledge’s When a Man Loves a Woman is just what she did. Why has it taken the world so long to appreciate her? HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Let England Shake (2011), PJ Harvey “Goddamn Europeans, take me back to beautiful England.” PJ Harvey may have sounded like she was channelling Boris and Nige when she made this striking album in 2015, but few Brexiteers would want to take this journey with her. Let England Shake digs deep into the soil of the land, where buried plowshares lie waiting to be beaten into swords. Death is everywhere, sometimes in its most visceral form: “I’ve seen soldiers fall like lumps of meat,” she sings on “The Words That Maketh Murder”, “Arms and legs are in the trees.” Musically, though, it’s ravishing: Harvey employs autoharp, zither, rhodes piano, xylophone and trombone to create a futuristic folk sound that’s strikingly original yet could almost be from an earlier century. CH

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Boy in da Corner (2003), Dizzee Rascal It’s staggering to listen back to this album and remember Dizzee was just 18-years-old when he released it. Rising through the UK garage scene as a member of east London’s Roll Deep crew, the MC born Dylan Mills allegedly honed his skills in production after being excluded from every one of his classes, apart from music. If you want any sense of how ahead of the game Dizzee was, just listen to the opening track “Sittin’ Here”. While 2018 has suffered a spate of half-hearted singles playing on the listener’s sense of nostalgia for simpler times, 15 years ago Dizzee longed for the innocence of childhood because of what he was seeing in the present day: teenage pregnancies, police brutality, his friends murdered on the streets or lost to a lifestyle of crime and cash. Boy in da Corner goes heavy on cold, uncomfortably disjointed beats, synths that emulate arcade games and police sirens, and Dizzee himself delivering bars in his trademark, high-pitched squawk. RO

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Hounds of Love (1985), Kate Bush Proof that a woman could satisfy her unique artistic vision and top the charts without kowtowing to industry expectations, Kate Bush’s self-produced masterpiece explored the extreme range of her oceanic emotions from the seclusion of a cutting-edge studio built in the garden of her 17th-century farmhouse. The human vulnerability of her voice and traditional instruments are given an electrical charge by her pioneering use of synthesisers. Thrilling and immersive. HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Blue Lines (1991), Massive Attack A uniquely British take on hip hop and soul that continues to influence booming modern genres like grime and dubstep, the Bristol collective’s debut gave a cool new pulse to the nation’s grit and grey. You can smell ashtrays on greasy spoon tables in Tricky’s whisper and feel the rain on your face in Shara Nelson’s exhilarating improvisations. HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Surfer Rosa (1987), Pixies It only takes 20 seconds of opening track Bone Machine to realise Pixies and producer Steve Albini have stripped down the sound of rock ’n’ roll and rebuilt it piece by piece. The angry smack of Led Zep drums, ripe bass, and sheet metal guitar straight off the Stooges’ Detroit production line are separated and recombined. Pixies’ sound is already complete before Black Francis embarks on one of his elusive pop cult narratives (“your bone’s got a little machine”). The tension between the savagery of his vocals and Kim Deal’s softer melodic tone won’t reach its perfect balance until their next album but their debut, Surfer Rosa is gigantic, and deserving of big, big love. Its “loud, quiet, loud” tectonics would prove so influential that Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain would later say he “was basically trying to rip off the Pixies”. CH

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Talking Timbuktu (1994), Ali Farka Toure and Ry Cooder If you ever doubt the possibility of relaxed and respectful conversation across the world’s cultural divisions, then give yourself an hour with this astonishing collaboration between Mali’s Ali Farka Toure (who wrote all but one of the tracks) and California’s Ry Cooder (whose slide guitar travels through them like a pilgrim). Desert meets Delta Blues. HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die The Great Gospel Men (1993), Various artists Compared to the blues, the incalculable influence of gospel music on pop, soul and rock ’n’ roll has been underplayed. It can be found in every song on this brilliant 27-track compilation. If you can’t hear James Brown in the foot-stomping opener “Move on Up a Little Higher” by Brother Joe May, you’re not listening hard enough. The road to Motown from “Lord, Lord, Lord” by Professor Alex Bradford is narrow indeed, but you could still take a side-turning and follow his ecstatic whoops straight to Little Richard, who borrowed them, and on to the Beatles who copied them from him. The swooping chord changes in James Cleveland’s “My Soul Looks Back” are magnificent. All the irreplaceable soul voices, from Aretha Franklin to Bobby Womack, were steeped in gospel. This is a great place to hear where they came from. Companion album The Great Gospel Women is a marvel, too. CH

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Hopelessness (2016), Anonhi “A lot of the music scene is just a wanking, self-congratulatory boys club,” said this angel-voiced, transgender artist in 2012. Four years later, the seismic drums and radical ecofeminist agenda of Hopelessness shook that club’s crumbling foundations to dust. The horrors of drone warfare, paedophilia and global warming are held up to the bright lights in disconcertingly beautiful rage. HB

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die In Utero (1993), Nirvana Kurt Cobain had one goal with In Utero: to pull Nirvana away from what he dubbed the “candy-ass” sound on Nevermind – the album that had turned them into one of the biggest rock bands on the planet – and take them back to punk-rock. He asked Pixies’ producer Steve Albini to oversee production. It didn’t exactly eschew commercial success upon release (it went on to sell 15m copies worldwide), but the heaviness the band felt as they recorded it bears down on the listener from the opening track. Disheartened by the media obsession with his personal life and the fans clamouring for the same old shit, In Utero is pure, undiluted rage. “GO AWAYYYYYYYYYYY” he screams on “Scentless Apprentice”, capturing the essence of Patrick Suskind’s novel Perfume: Story of a Murderer and using it as a metaphor for his disgust at the music industry, and the press. RO

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Curtis (1971), Curtis Mayfield Curtis Mayfield had been spinning golden soul music from doo-wop roots with The Impressions for more than a decade before releasing his first solo album, which contains some of his greatest songs. While some point to the 1972 Blaxploitation soundtrack Superfly as the definitive Mayfield album, Curtis is deeper and more joyous, its complex arrangements masterly. Mayfield’s sweet falsetto sings of Nixon’s bland reassurances over the fuzz-bass of “(Don’t Worry) If There Is a Hell Below We’re All Going to Go”; doleful horns give the politically conscious “We the People Who Are Darker Than Blue” a profound emotional undertow; “Move On Up” is simply one of the most exhilarating songs in pop. To spend time with Curtis is to be in the presence of a beautiful soul. CH

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Rumours (1977), Fleetwood Mac Before they went their own way, Fleetwood Mac decided to tell a story that would be the quintessential marker for American rock culture in the Seventies. As Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks tossed the charred remains of their relationship at one another on “Dreams” and “Go Your Own Way”, the rest of the band conjured up the warm West Coast harmonies, the laid back California vibes of the rhythm section and the clear highs on “Gold Dust Woman”, in such a way that Rumours would become the definitive sound of the era. At the time of its release, it was the fastest-selling LP of all time; its success turned Fleetwood Mac into a cultural phenomenon. RO

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die Are You Experienced? (1967), Jimi Hendrix A virtual unknown to rock fans just a year before – Hendrix used Are You Experienced? to assert himself as a guitar genius who could combine pop, blues, rock, R&B, funk and psychedelia in a way no other artist had before. That’s even without the essential contributions of drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Noel Redding, who handed Are You Experienced? the rhythmic bridge between jazz and rock. Few album openers are as exquisite as “Purple Haze”. Few tracks are as gratifying, as sexy, as the strut on “Foxy Lady”. And few songs come close to the existential bliss caused by “The Wind Cries Mary”. Hendrix’s attack on the guitar contrasted against the more polished virtuosos in rock at the time – yet it is his raw ferocity that we find ourselves coming back to. Few debuts have changed the course of rock music as Hendrix did with his. RO

The 40 best albums to listen to before you die We Are Family (1979), Sister Sledge Disco’s crowning glory is this album that Chic’s Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards made with Kathy Sledge and her sisters Debbie, Joni and Kim. Nile and ’Nard were at the peak of their powers, classic songs were pouring out of them – We Are Family was released in the same year as the epochal “Good Times” by Chic – and this album has four of them, “Lost in Music”, “He’s the Greatest Dancer”, “Thinking of You” and the title track itself. Sister Sledge gave Rodgers a chance to work with warmer, gutsier vocals than the cool voices he used to give Chic records such laid-back style and the result is a floor-filling dance party, punctuated by mellow ballads. CH

“I do know that Lou Reed himself didn’t really keep a lot of lyrics that he may have scratched out or older things. He was very much a forward-looking person,” Hiam says.

Those around Reed, however, might hold on to “things that might otherwise seem like details”, such as receipts for dinner and drinks – anecdotal titbits that only make sense as pieces of a larger puzzle.

What has been rescued, then? It all fits into eight parts. The first comprises 100 audio recordings made between the 1960s and 2012, including a 1965 reel that is believed to be one of the earliest known recordings of Reed’s original work. Then come the office files, including fan mail, licensing papers, financial documents – all the components of Reed’s business affairs. The third part, called “tours and performances”, documents Reed’s life on the road. Here you will learn that Reed apparently had a reputation for blaming wrong notes on “the nearest technician”, post-dating “all checks”, and constantly straying from his own setlists.

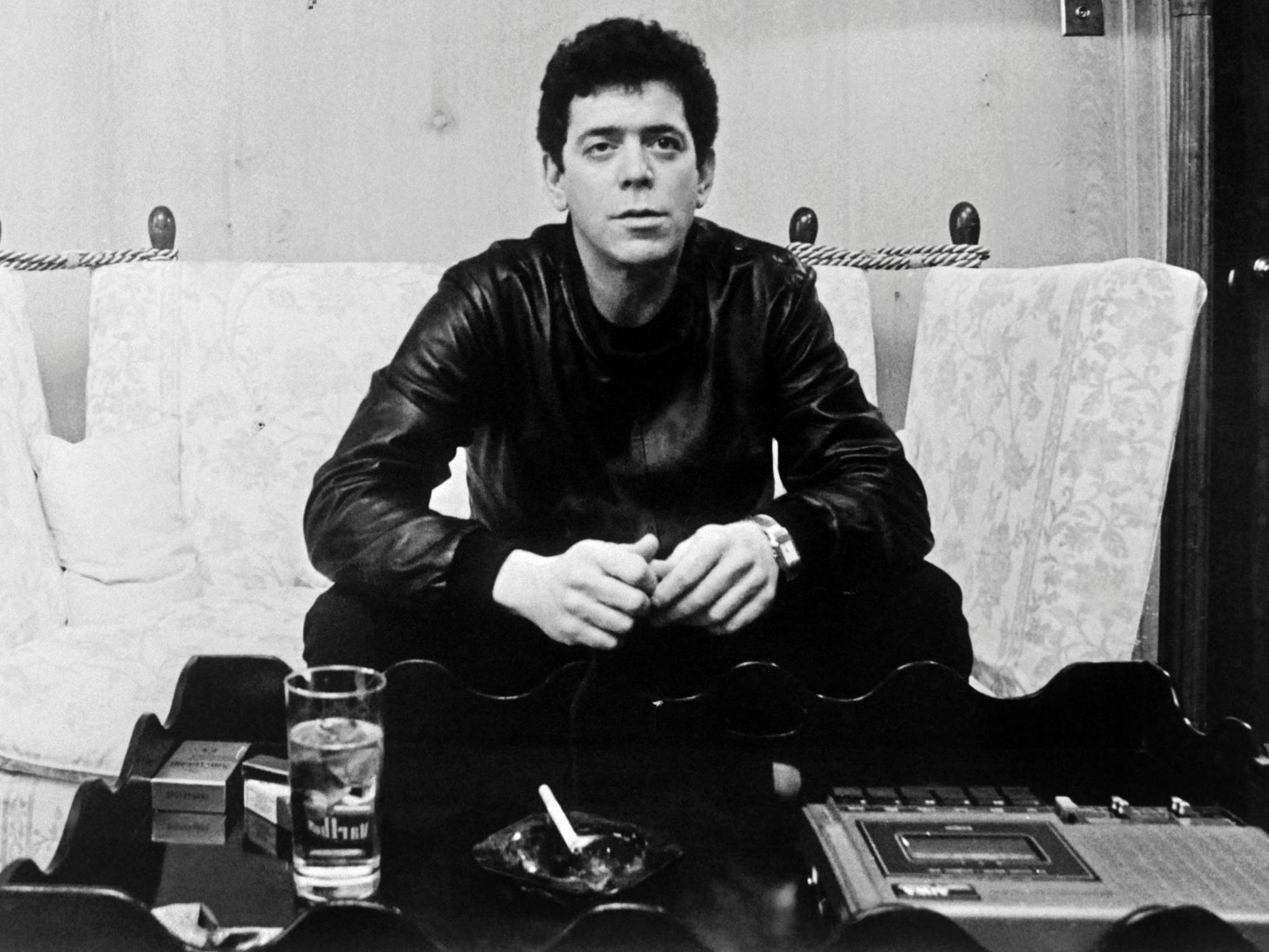

Reed onstage at the Crystal Palace Garden Party in September 1973 (Rex) Then come photographs, both by and of Reed, including some of his tai chi practice and candid shots of friends and family. The fifth section, “Writing”, includes typed manuscripts, drafts of short stories, speeches, poetry, and lyrics from Reed’s commercially released albums – all typed and, alas, free of annotations. “Art and Design”, the sixth chapter of the archive, embodies Reed’s visual life, from album artwork to postcards, posters, and promotional shirts. Press clippings come next, followed by Reed’s “personal collection”, a miscellaneous assemblage of yearbooks, cameras, glasses, personal letters, passports, Tai-Chi materials, and even a Halloween costume.

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Sign up Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Sign up Despite those titbits, Hiam acknowledges that most of the archive reflects Reed’s professional existence, rather than his personal life. It is fitting, in a way, that Reed – a notoriously tricky interviewee who revealed only as much of himself as he wanted – would remain somewhat mysterious even in death. Hiam points out that there may be logical reasons why Reed’s archive isn’t full of emotional, intimate letters to his family: a native New Yorker, he only left his hometown to go to college, and even then, only travelled so far as Syracuse in the state of New York. Besides, as a child of the 20th century, he would most likely have picked up the phone to catch up with his relatives, rather than put pen to paper.

Reed’s relationship to his parents has been a subject of speculation throughout his career. His 1974 song “Kill Your Sons” is said to have been inspired by his experience receiving electroshock therapy as a college student. In a 2015 essay , his sister, Merrill Reed Weiner, denied claims that the treatment was intended to repress “homosexual urges” on the part of her brother. Instead, she painted a dire picture of Reed’s mental state, writing: “Lou was not able to function at that time. He was depressed, anxious, and socially unresponsive. If people came into our home, he hid in his room. He might sit with us, but he looked dead-eyed, non-communicative.”

Reed live in 1977 (AFP/Getty) “My parents were like lambs being led to the slaughter – confused, terrified, and conditioned to follow the advice of doctors,” she added. “They never even got a second opinion. Told by doctors that they were to blame and that their son suffered from severe mental illness, they thought they had no choice.”

Reed’s archive is not entirely an exercise in control. Hiam, who cautions that it’s hard to know which items Reed chose to have in his possession and which were gifted or sent to him, was surprised to see a Kiss album in Reed’s record collection. (Judging by Hiam’s description, he’s referring to Music from ‘The Elder’ , Kiss’s ninth studio album – a commercial failure – on which Reed had a writing credit). Some things, naturally, didn’t make the cut: “medical records, personal tax forms, and things that are family-oriented, that have deeply personal information about living people and family”, says Hiam. Some artists, he adds, may give their more personal materials to an archive after sealing them for a number of years, but he’s not aware of any plans to do so on Reed’s side.

Those who have seen the Lee Israel biopic Can You Ever Forgive Me? will know what consulting an archive entails. Materials must be requested. Jackets and bags must be set aside. You may lose yourself in a myriad of call slips and registration forms. But here the archive remains, ready to be seen – tiny fragments of Lou Reed’s life coming together at your fingertips.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies