Loved the music, hated the bigots

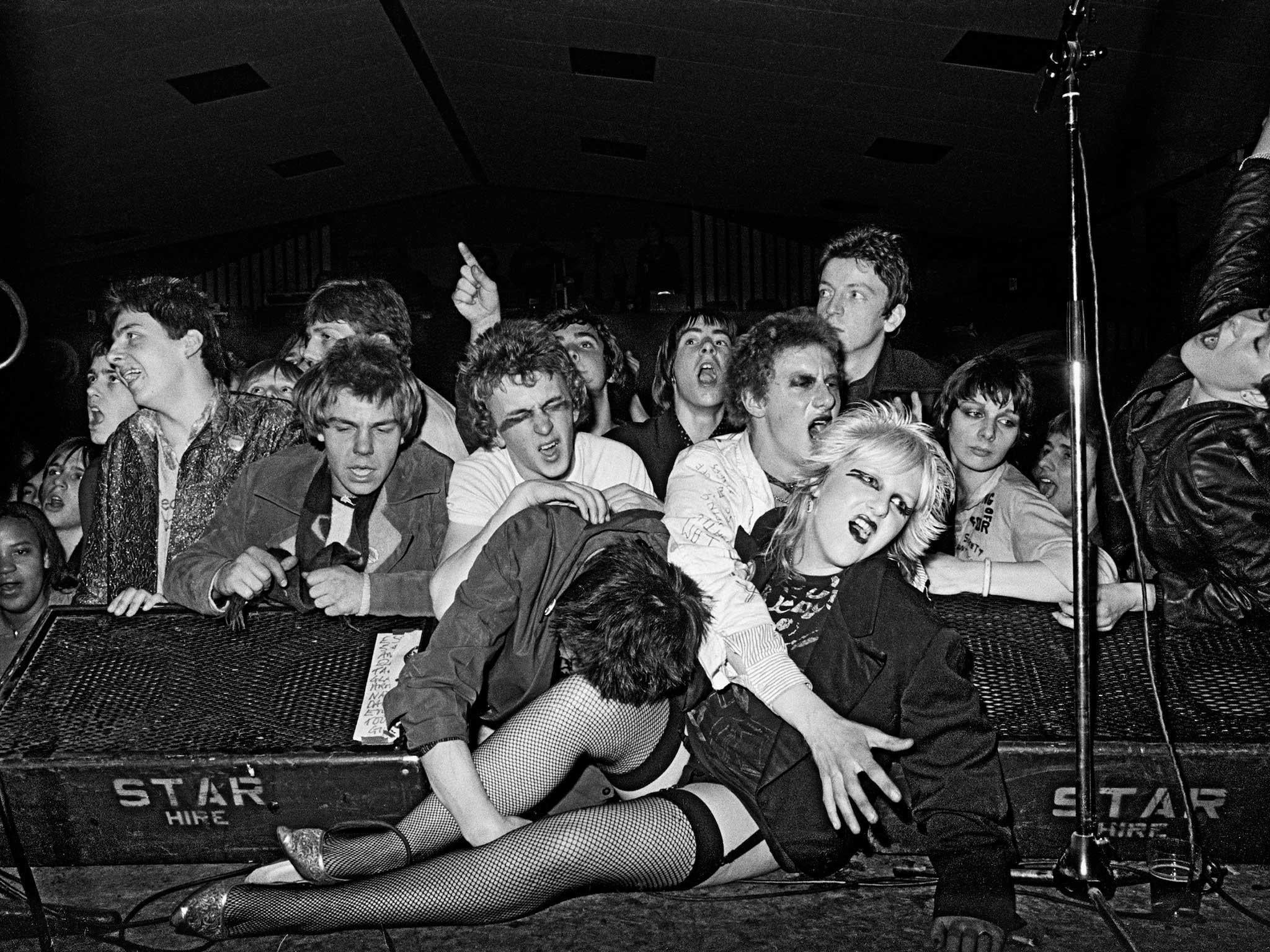

Forty years ago this summer, when Rock Against Racism was born, photographer Syd Shelton was there to record it. As his new show opens, he explains how a musical youth movement stemmed the rising tide of prejudice

“Storm Over the Two-Wife Migrants”. “Another 20,000 Asians are on the Way”. “Scandal of Day-Tripper Immigrants”. Not today’s headlines – though they could easily be – but those from 40 years ago… and ones that helped to give birth to one of the biggest grassroots movements in recent history.

In the summer of 1976 music, politics and culture intersected to create a wholly British response to the xenophobia that was threatening to engulf the country. The rhetoric of racism wasn’t tackled with mealy-mouthed rejoinders, nor was violence met with violence. Instead, the weapon of choice was music. And Rock Against Racism was born.

Which, in a way, was rather appropriate. Because, although this was the age of Enoch Powell – who was to remain in Parliament for another eight years — as well as institutionalised racism and violent marches, it was the words of a musician that sparked the creation of Rock Against Racism: Eric Clapton.

On 5 August 1976 Clapton — apparently drunk, certainly angry — took the stage at the Birmingham Odeon and between songs railed against Britain becoming “a black colony”, voiced his support for Powell, who eight years earlier had made his infamous Rivers of Blood speech just down the road, and exhorted his audience to “get the foreigners out” and “keep Britain white”. Clapton later tried to downplay his words, saying they weren’t aimed at any particular minority group but were a response to what he saw as the takeover of London by wealthy Arabs. But the damage was done, and the counter-attack was launched.

A group of artists, writers and musicians, among them photographer Red Saunders and activist Roger Huddle, had already been pondering some kind of cultural response to the rising tide of racism and the grip the far-right National Front were exerting on the nation. The Clapton rant provided them with an inciting incident and they wrote to the New Musical Express, decrying his comments and suggesting the creation of a movement to fight home-grown fascism – Rock Against Racism.

The fledgling organisation was inundated with responses to the letter. Over the next five years they put on gigs, festivals and marches under the slogan Love Music, Hate Racism. Performers who played under the Rock Against Racism banner included Elvis Costello, The Clash, Misty in Roots, Sham 69, The Who’s Pete Townshend and The Specials.

And Syd Shelton was there to document this incredible time with his camera. “I was out of the country when the letter was sent so I wasn’t a signatory to it,” Shelton says. “But as soon as I got back I made contact with Red Saunders. I got involved from there, we got on very well and we’re still friends 40 years later.”

Shelton, born in Pontefract, West Yorkshire, in 1947, was at the time working as a rock photographer and graphic designer, and he found himself devoting more and more time to helping out with RAR. He says, “We had committee meetings in London. Sometimes nobody would come. The next week Misty in Roots and Aswad would call in. We made it work because of the nature of the people involved. We had that rebel aspect to us, I suppose.”

While he worked with the committee organising events, Shelton also began to document with his camera the gigs held to raise money and awareness for the cause. “From 1976 to 1977 was the formative period of RAR,” he says. “There were a lot of small gigs in pubs. Then Lewisham happened, and that was a pivotal event.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

He’s referring to what has become known in popular culture as “The Battle of Lewisham”, when 5,000 National Front supporters marched across the south-east London borough in August 1977. Several anti-fascist organisations organised counter-demonstrations and marches, and there were bloody and violent clashes.

The Lewisham pot had been simmering for some months before that, though. Shelton says: “It’s an area that had the largest concentration of immigrant people in London. The authorities had organised a campaign against muggings, but the sub-text was that it was black people who were responsible. It was a drip-drip-drip of propaganda. As a result the police raided 30 homes in Lewisham and arrested 21 young people and locked them up.”

Shelton took a photograph of one young man, Christopher Foster, who was just 16 when he was arrested. His father, David Foster, was instrumental in the establishment of the Lewisham 21 Defence Committee to support those arrested. The headquarters of the campaign was the front room of the Foster family home.

Two months later the Battle of Lewisham occurred. Shelton says, “It was a very significant day, and after that we realised we were dealing with institutional racism from the police and the authorities as well as organised racism from the National Front. Even if people weren’t members or supporters of the NF, there was a lot of casual racism around at that time. The Black and White Minstrel Show was on TV. It was only the decade before that there were notices in windows of guest-houses, ‘No dogs, no blacks, no Irish’.”

That photograph of young Christopher Foster, flanked by his determined-looking father and his mother, eyes downcast, is now included in an exhibition of Shelton’s work covering the Rock Against Racism years, which is running at the Impressions Gallery in Bradford, West Yorkshire, until the beginning of September.

His photographs cover the music’s attack on racism: Tony James of Generation X playing bass guitar with Sham 69 at Central London Poly, a gig infiltrated by a racist gang; Jimmy Percy of Sham 69 talking to a carnival crowd after the band had been forced to pull out of playing due to death threats; Joe Strummer of The Clash at a benefit gig in Southall.

One shot shows Jeff Walwyn, aka Skully Roots, riding a huge speaker like a bucking bronco at the Leeds Rock Against Racism club. This was set up by Paul Furness, who one day had the NME letter about Eric Clapton shoved under his nose, and decided he wanted to set up club nights for northern anti-racist supporters. Furness says: “We ran for about 18 months during 1978 and 1979. It was the perfect timing for Rock Against Racism, really – we had punk bands and reggae sound systems, it was highly political.”

The Leeds club put on gigs by local bands including The Mekons and Gang of Four, and played host to Stiff Little Fingers and the only RAR gig to be played by Joy Division. “We had a huge following and there were people at those gigs who we had no idea who they were but went on to be famous… Marc Almond and Damien Hirst, for example,” Furness says. “Syd Shelton came up to take some photos and that’s where I first met him.”

Furness has donated some memorabilia from the Leeds RAR club which is also on display alongside the photographs. All shot in monochrome, Shelton’s pictures illustrate the binary nature of racism; black and white, them and us, light and shade. And it was never meant as a special project; taking pictures was just what Shelton did.

“It took the distance of time to make me realise there was a narrative here, something I never saw at the time,” he says. “I was too close to it, I think.” It’s not so well represented here, but in the show many of the photographs are just of kids who were around the scene on Shelton’s RAR odyssey, “and that was intentional. I wanted to put a face to the racism people were suffering, show the humanity.”

And Shelton is no impartial recorder of history. “I reject the notion that the photographer is an impassive observer,” he says. “You construct the argument of what you want to say through the language of photography, through the shots you take and the angles you choose.”

Back in the aftermath of the Battle of Lewisham, Rock Against Racism wanted to make a bigger point than ever before. “We wanted to do something much more special than just gigs in pubs,” says Shelton. “We wanted to do an anti-racist Woodstock.” That took place in Victoria Park in Hackney, in the spring of 1978 after Shelton and the committee (along with the Anti-Nazi League) begged, borrowed and blagged a stage and PA equipment and used their contacts in the music industry to get bands such as The Clash, X-Ray Spex and Tom Robinson.

He remembers: “We told everyone to meet in Trafalgar Square, and people said to us, ‘you’re mad, that’s seven miles from Victoria Park. Nobody’s going to walk that far’.” He pauses, then says with some satisfaction: “We got 100,000 people. We had seven flatbed trucks with bands on the back, led by Misty in Roots. It was a seven-mile party all the way to Hackney.”

Rock Against Racism was wound down in 1981, in a way a victim of its own success. Things were changing, sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly. Shelton says: “Back in the mid-1970s there were something like two black footballers in the whole of the football league. Look at the England team that was at the Euros this summer. When we started punk was just taking off and there was a lot of reggae about, and we saw an affinity between the two. Then ska and Two-Tone picked up the baton, and we had bands such as Madness and The Specials, who were multicultural bands and they were pushing through to the mainstream, taking the message to everyone.”

Not that Shelton by any means thinks that the battle is close to being won, especially with the rise in xenophobic hate speech and assaults in the wake of the EU referendum. “It’s a constant fight,” he says. “We always see scapegoating in our society; it’s just that the targets shift. We see some media outlets having a go at migrants on a daily basis and once again we have that drip-drip-drip of propaganda.”

Syd Shelton’s photographs form a document of a world that seems so long ago, yet is also horribly familiar thanks to recent events. He says: “I think back in 1976 we would all have hoped that things would be a bit better 40 years on.”

He’s approaching 70 now and lives in Hooe, East Sussex, and though he’s no longer in the thick of the volatile and dangerous world of clashing communities, he refuses to stop being angry. “Nobody’s born racist; it’s something you have to learn. That’s a very tough thing to fight against constantly, but it’s something we have to do.” He tells me as we speak he’s looking out not on urban warfare but fields and cows. So have Syd Shelton and his camera retired from activism? He considers this. “Despite the view,” he says, “I think I’m still a rebel.”

Syd Shelton’s ‘Rock Against Racism’ – curated by Mark Sealy at Autograph ABP, in collaboration with guest curator Carol Tulloch – is at the Impressions Gallery in Bradford until 3 September. On 23 July, Syd Shelton will be in conversation at the gallery with Carol Tulloch

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies