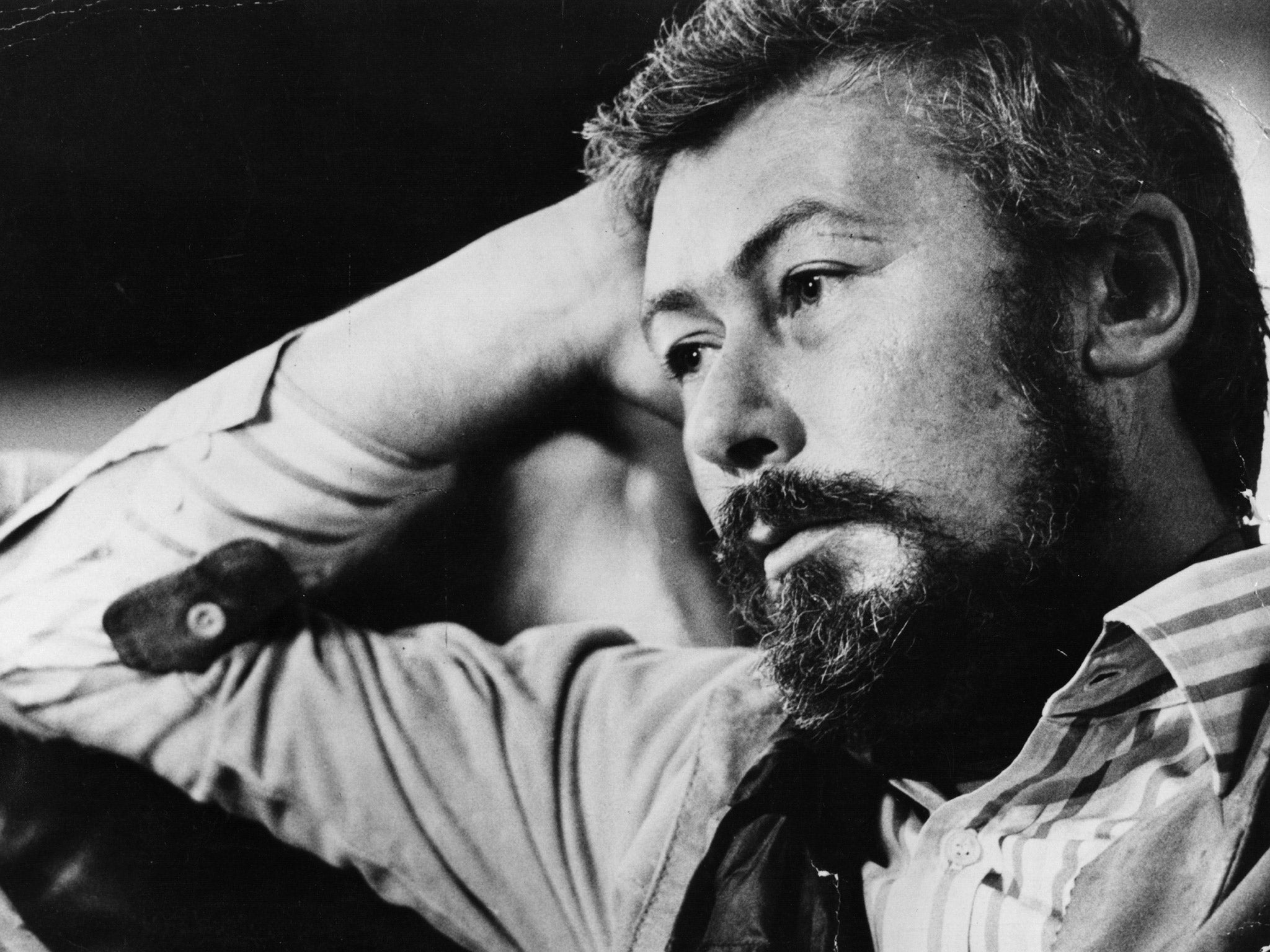

John Osborne: New biography records the day the Look Back in Anger playwright was chased by an angry mob

John Osborne, the writer of 'Look Back in Anger' and 'The Entertainer', was hailed as Britain's most provocative playwright. But, as this extract from a new biography by Peter Whitebrook reveals, his first and only musical was such a disaster that after the opening night, he was chased up Charing Cross Road by an angry mob - and fled to France soon after

If there was one thing The World of Paul Slickey did not lack, it was publicity. By May 1959, the imminent West End opening of a jazz-pop musical by John Osborne, satirising the ethics of the gossip columnists of the popular daily press, had feverishly preoccupied journalists and, inevitably, gossip columnists for weeks. At 30 years old and the author of Look Back in Anger and The Entertainer, Osborne was both fêted and denounced as the original Angry Young Man. He was "Britain's most provocative playwright". For three years now, his name had cropped up in newspapers almost every week, both in serious cultural commentaries and gossip columns relaying the perilous state of his marriage to Mary Ure and his various "Angry" pronouncements on subjects ranging from the Conservative Party to women and to the H-Bomb, with asides on more or less anything else that took his fancy.

Rehearsals for Slickey had been chaotic. Osborne, who was also directing, had obstinately refused appeals for rewrites. On a pre-West End provincial tour, the show had been pelted by audience derision and local critical disdain. Nevertheless, David Pelham, the show's producer and a man as combative as its creator, had poured money into advertising the London opening at the Cambridge Theatre, and invited an impressive list of eminent figures to the first night on 5 May, many of whom, impervious to, or perhaps intrigued by, the storm warnings in the press, actually turned up.

Culture news in pictures

Show all 33Looking around the stalls, Osborne noticed Noël Coward, John Gielgud, Cecil Beaton, Michael Foot, the editor of Tribune, Aneurin Bevan, and John Profumo, the Conservative Secretary of State for War, soon to be embroiled in his own difficulties with gossip columnists fascinated by his liaison with a nightclub hostess. George Devine, Osborne's mentor at the Royal Court Theatre, was there, and a formidable phalanx of restive critics and journalists. High in the balcony sat an intimidating gathering of Gallery First Nighters, a band of theatre enthusiasts who attended most West End premieres, queuing for the cheaper seats and led by a large, late middle-aged cockney known as Sophie, the mention of whose name struck terror into the hearts of many playwrights. The First Nighters "knew what they liked" and their loudly voiced approval or censure during the performance could set the tone of the evening.

Within minutes of the curtain going up, it was from Sophie's wreath of supporters that the first growls of dissent came, like a wind whipping up before a storm. By the second act, the squall was gusting alarmingly through the circle to the stalls. As singers pilloried the popular press, celebrated adultery, mocked Conservative middle class and the supporters of capital punishment, and as a reprobate priest and jiving dancers lampooned an aristocrat's funeral, the gales of protest from the audience almost equalled the sound from the stage. The clack-clack of seats tilting back as loudly complaining ticket-holders began pushing their way out of the theatre, added to the chaos. At the final curtain, the national anthem, reorchestrated to include a loud, defiant raspberry played on the trombone, provoked howls of derision while the cast took their curtain call to a fusillade of boos and contemptuous whistling, "the most raucous note of displeasure", pronounced the Evening Standard, "heard in the West End since the war".

Sitting in the stalls, Aneurin Bevan "bowed his head and put his hands over his ears" as pandemonium erupted around him and from the stage the leading actress retaliated by mouthing "four naughty words" towards the balcony. "The forward rows of the Debrett and show business audience heard them," chided the Daily Mail. "Noël Coward and Aneurin Bevan could have heard."

Coward, however, did not flinch. Instead, he remained sitting bolt upright in his seat much in the manner of the implacable Naval captain he had played during the war in the film of In Which We Serve. "Never in all my theatrical experience," he recorded in his diary, "have I seen anything so appalling. Bad lyrics, dull music, idiotic, would-be-daring dialogue, interminable long-winded scenes about nothing, and above all, amateurishness and ineptitude."

The World of Paul Slickey, he concluded, revealed the so-called Angry Young Man to be "no leader of thought or ideas" but instead "a conceited, calculating young man blowing his own trumpet". Coward nevertheless retained an actor's sympathy for the performers, the following morning dispatching a generous telegram to Dennis Lotis, who had played the eponymous leading role. "Congratulations on a charming performance," he wrote, "in very trying circumstances."

Circumstances for Osborne, however, had become hazardous. Someone warned him that a crowd of snarling ticket-holders was massing at the stage door. When the offending dramatist emerged, it swooped upon him "like a lynch mob", jostling and shouting. Dodging through the scrum, Osborne sprinted up Charing Cross Road, the crowd in baying pursuit, until he managed to scramble into a luckily passing taxi and was safely carried away home. The escapade later became one of his favourite anecdotes: "I must be the only playwright this century to have been pursued up a London street by an angry mob," he calculated proudly.

The following morning, he awoke to find the critics united in a Greek chorus of reproach. "The ordeal lasts for three boring hours", complained the Manchester Guardian. ". . . extraordinary dullness", concurred The Times. Osborne has begun "to slosh at everything he does not like", related The Daily Telegraph, "including tasteless jibes at religion". At lunchtime, the embattled playwright, "a pale face above a red tie", appeared at the theatre, where Pelham had hastily arranged a retaliatory press conference. "Smoking a thin, seven-inch cigar', from which the Daily Herald spotted that he had not removed the band ("presumably one of his anti-Establishment attitudes"), Osborne proclaimed that the critical assault was exactly what he had expected from London theatre reviewers, "none of whom has the intellectual equipment to judge my work. They are a bunch of professional assassins."

Undeterred, Pelham promptly came up with a survival strategy based upon the principle of attack being more effective than defence. The World of Paul Slickey would be enlisted as a tool in the proletarian class struggle. All their hopes now lay with the Labour Party and the trade unions. If Tories and the middle classes jeered Slickey, he reasoned, then surely socialists and the working classes would cheer. In fact, they were already doing so. The evidence was in the Daily Herald, a newspaper supporting the Labour Party and in which Michael Foot was bathing Slickey in a rosy anti-capitalist glow. "Osborne attacks the whole works," he enthused, "the mechanics of success, the whole stuffy post-war attempt – assisted by the bright boys of Fleet Street – to restore a British society that is drenched in hypocrisy and phoney values. Heavens above," he exhorted, "let them look at themselves, the pious men of Suez, the pinheaded champions of nuclear complacency, the immortal emasculators of freedom, the capital punishers with their saintly eyes fixed on the popularity polls and the whole apparatus of gossip columns and television tomfoolery that helps keep them in power. Yes, take a look through John Osborne's savage but compassionate eyes." And if more compelling evidence were needed, Tribune, the socialist weekly, lauded Osborne for giving "the British ruling class the theatrical trouncing of its life".

This was extravagant, arguably preposterous praise, but Pelham seized the day and plunged remorselessly onwards. Instead of being smothered, the dismal verdicts of the daily press were bruited abroad as the terrified cries of reactionaries in retreat. Pelham unleashed a barrage of advertisements promising that: "'THEY' don't like it, but YOU will!" Tribune rallied to the cause. "Slickey: The Argument Rages", blared its front page on 5 June, while its correspondence columns pulsed with views both for and against.

But with Slickey leaching money, Pelham fired off a distress call in a further frantic attempt to lure audiences. An "SOS to the Labour Party" was urgently transmitted in which tickets at embarrassingly reduced prices were offered to bands of trade unionists. "Workers UNITE", cries an ailing Slickey, trumpeted the Daily Herald, almost hoarse with desperation. "Roll up all those transport workers! Forward the miners!"

But Herald and Tribune readers remained at home, the transport workers failed to be transported and the miners stayed resolutely in the coalfields. Elsewhere in the West End, My Fair Lady was well on its way to making over £100,000 a year. But with audiences dwindling and weekly running costs of almost £4,000, The World of Paul Slickey closed after only six weeks, the Battle of Cambridge Circus ending miserably in the decisive defeat of financial loss. The show has never been revived, and neither has the music, which the Telegraph thought "nearly always pleasant", been recorded.

As for Osborne, flight seemed the appropriate response. Hardly had the tempest of the first night subsided, than he turned gratefully to the embraces of Jocelyn Rickards, the show's costume designer and his latest extra-marital lover, and escaped with her to France, at the wheel of one of his swaggering emblems of success: a green open-top Jaguar XK150.

This is an extract from 'John Osborne: Anger is Not About...' by Peter Whitebrook (Oberon Books, £20)

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies