Three glorious decades: The best of the Independent's arts journalism so far

A gig review in the style of The Ancient Mariner… how to make a toaster into conceptual art… why gays like musicals. We’ve selected some of the best of The Independent’s arts journalism since 1986

1988

Musicals

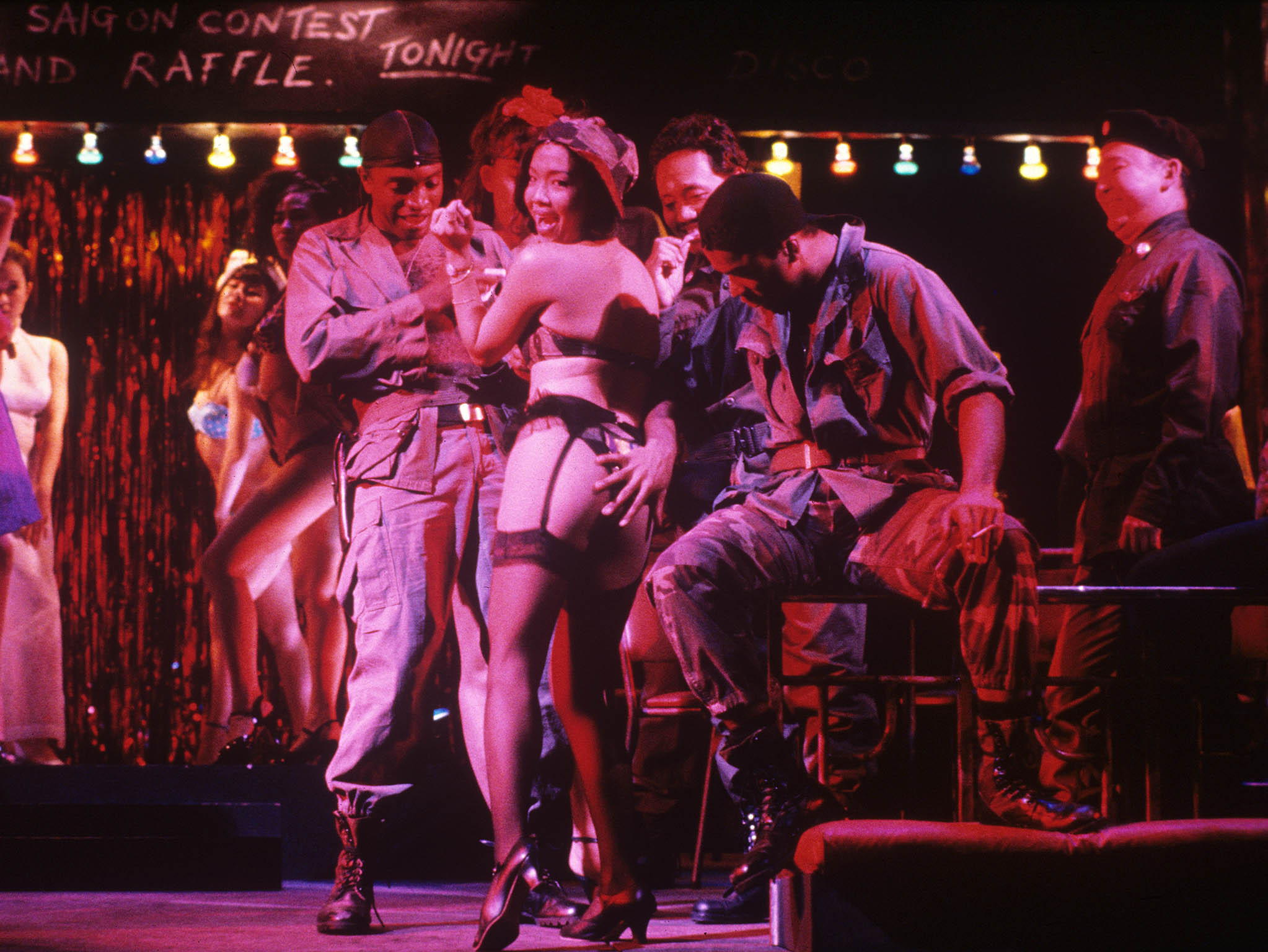

Mark Steyn on Miss Saigon

“I did a lot of research,” said Jonathan Pryce, who plays Miss Saigon’s resourceful pimp, in this paper last week, “and I found that people in Saigon at that time did, in fact, sing everything.”

There is more to this joke than meets Pryce’s heavy-lidded Oriental eye-pieces. The most interesting question in musical theatre today is whether “singing everything” automatically means abandoning reality.

The through-written musical gets by on subjects like Phantom of the Opera because we’re prepared to accept lush declarative tunes, flowery lyrics and general swanning about from larger-than-life figures sufficiently remote from our own lives. But are we doomed to a diet of Phantoms, or can the form grapple with contemporary characters who speak normally and wear modern dress?

On the evidence of Aspects of Love, the answer was no: Andrew Lloyd Webber seemed unable to scale down his music to the milieu of the novella. Opera, of course, has never been bothered enough even to acknowledge the dilemma, which is why, for 60 years, the major innovations in sung texts and drama in music have taken place elsewhere.

For these reasons, Cameron Mackintosh’s latest offering represents the most hopeful development in the nascent British musical tradition he helped establish. Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil have seized a Puccini subject – the old Madame Butterfly routine – and managed its potentially hazardous transfer to Vietnam extremely smoothly.

Miss Saigon takes the grand passions of opera and sets them to the less florid and self-conscious musical idioms of the everyday world. That it works so well is due to self-effacement and restraint on Schönberg’s part. His melodies may not be, in the purest sense, as good as Puccini’s but what seems to me indisputable is that they are better attuned to the needs of situation and character (without resorting to heavy-handed leitmotifs), and that they follow a much tauter gameplan than Giacosa and Illica’s libretto.

Unlike Lloyd Webber, Schönberg has not forgotten the importance of variety: even a score that aspires to the musicality of opera should still have tempo and rhythm. There is a neurotic insistence in much of the music, even in some of the ballads.

And, although there are a few pentatonic Orientalisms, the composer and his orchestrator, William D Brohn, are in the main more cunning, preferring slightly skewed western forms, underlining the cultural corruption of Saigon under the French and Americans. Jonathan Pryce’s wiggling pimp gets the best of these, “The American Dream” (a good shot at out-Kander-&-Ebbing Broadway), a sardonic slithering parody of Astaire, backed by a weird perversion of a musical chorus line, that seems destined to become his “Gotta Pick a Pocket Or Two”.

Culture news in pictures

Show all 33Only the love-ballads remain unsullied: “How in one night have we come so far?” But even this sentiment, the last wondering line of a translucent duet, reveals itself mockingly as the cruellest self-deception, bitterly reprised by Kim (Lea Salonga in a powerful West End debut, a shy flower who eventually withers into bleak resignation) three years later in Bangkok after Chris has returned – but with his wife.

Enveloped by a larger tragedy, even the tawdriest glitterball smooch tune is ennobled. “A song sung on a solo saxophone,” wails Chris in rock balladeer fashion, a sweaty marine hugging his Saigon bar-girl.

“It’s telling me to hold you tight/And dance like it’s the last night of the world.” For once, the exaggerated sentiments of love songs hold up, as the set smoothly disintegrates and, oblivious in mid-embrace, the couple are pulled backwards and disappear. Within moments, the clutter of the city has vanished; the lovers who close-up had filled the stage are suddenly shrunk to two tiny people in an empty cavern.

This is the last night of the world: the fall of Saigon. Silver slatted blinds snap shut, and the stage is empty: the city, cleansed and re-educated, is born again to the brutish, jarring harmonies of the Vietcong as red banners and yellow stars burst on “The Morning Of The Dragon”.

John Napier’s designs and Nicholas Hytner and Bob Avian’s fluid, filmic staging produce other strong visual moments: the workers erecting a giant statue of Ho Chi Minh as Kim stands over the murdered Commissar; the Vietnamese desperately scrambling against the wire mesh of the embassy compound as an overloaded US helicopter shakily starts its ascent.

It’s not a perfect show. Maltby should know better than to rhyme “phone” with “home”, and the confrontation between Kim and Chris’s wife peters out for want of a finely focused lyric. But, overall, Miss Saigon gives us an absorbing and moving love story and packs a considerable political punch. For those of us worn down by the simple-minded pop pageantry of British musicals, it marks a significant advance for the form, and a stunning achievement for Cameron Mackintosh.

I hope this is not, as he threatens, his last show, because Mackintosh is one of the few producers who nurtures his shows through the inevitably difficult gestation period. By fusing the sweep of opera with the naturalism of the musical play, Miss Saigon is the best of the new school of the British musicals.

1988

Pop

The Rime of the Ancient Rockers – Kevin Jackson reviews Status Quo at Wembley Arena in the style of Samuel Taylor Coleridge

It is an ancient rocking band

(Of chords, they know but three)

And they play their usual Christmas gig

To crowds at Wembley.

Around me thronged the ageing fans

With sons and grandsons, too;

Their hair was lank, their armpits rank –

They were a ghastly crew!

Lager, lager everywhere;

The hot dogs they did stink

Lager, lager everywhere,

I felt the worse for drink.

Eftsoons there rose a dreadful howl,

To chill the blood of man;

Fast closed the doors, and, to a roar

“Sweet Caroline” began.

‘What monstrous noise is this?’, I screamed,

‘Twould make a dead bird cry!’

But a thousand, thousand hairy forms

Raved on; and so did I.

I looked upon the stage and saw

A triple-headed beast;

I looked upon the howling crowd

And prayed to be released.

Their leader smiled – a sight as vile

As any corse’s grin;

He leered with pride – “Roll over!” cried,

“Lay Down, and Let Me In!”

By one and two, in denim blue,

They gave vent to their songs –

A wailing like a damned soul

Who for salvation longs.

The riffs they came as thick as ice

In a distant Southern clime

And each was like the one before;

I lost all track of time.

The riffs they came as thick as snow

That is by tempest tossed

And every riff was heavier than

A murdered albatross.

From “In my Chair” to “Break the Rules”

I wept, ‘Enow! Enow!

My ears are flayed!’; and then they played

“You’re in the Army Now”.

‘What is the curse that brought me here

To suffer untold woe?’

I begged the skies; and in reply,

The fans all chanted ‘Quo!’

The fans they leapt and punched the air

As though to strike the stars

And while they raved, the others waved

Inflatable guitars.

The fans they leapt and clawed the air,

As if they played on frets;

Like wraiths on an unholy night

Of fevers, pains and sweats.

The fans they raised their straight right arms

And Zippos set alight

And each right arm burnt like a torch,

A torch that’s borne upright.

The dandruff flew; the volume grew

The heads they banged as one;

With single roar, they yelled ‘Encore!’

I knew my time was done.

No human creature could sustain

Such hell-deliver’d sound;

I took a swig of laudanum

And fell down in a swound.

The bouncers came and dragged me out

Of every sense forlorn;

A sadder and a deafer man

I rose the morrow morn.

1990

Film

Adam Mars-Jones on Goodfellas

Martin Scorsese’s GoodFellas (18) sets out to give its genre, the gangster movie, a jolting transfusion of realism. The film is drawn from a book by a crime reporter, Nicholas Pileggi, and gives a knowledgeable view of what it never gets round to calling the Mafia. We learn, for instance, that the hero, Henry (Ray Liotta), and his older confederate Jimmy (Robert De Niro) cannot be “made” – promoted to the inner circle of power – because they aren’t fully Italian. Their Irish blood excludes them.

But, despite the strength and novelty of its details, GoodFellas remains in the shadow of the film that most memorably combined carnage and Italian cooking, spilt blood and appetising spaghetti sauce: The Godfather. Scorsese competes with Coppola not so much by increasing the bloodiness – though this is of course a violent film – but by exaggerating the amount of cooking. Dramatising a world in which the only uncorrupted culture is cuisine, he manfully celebrates cuisine. The sausages gleam in the pan; the sauce is rich and lustrous.

Scorsese’s problem, particularly in a film that covers three decades and runs for two-and-a-half hours, is a chronic shortage of innocence. At least in The Godfather, women and children might be kept in the dark about the Family to which they belonged, and the Al Pacino character had a status as a war hero that enabled him for a time to resist the claims of blood. In GoodFellas, the world of crime pulls everything into itself, and it isn’t possible to hesitate even for a moment on the edge of the whirlpool.

Scorsese’s solution is a sort of resourceful bad faith. He implies that sooner or later his characters will sicken of crime, but they never do. At the end of the first scene, for instance, after a vile murder, Scorsese freeze-frames Henry’s face, bathed in the red glow of a car’s tail-light; he seems to be realising the full horror of his choices. (Throughout, Scorsese uses freeze-frames with a voice-over as the equivalent of reaction shots, to allow back into the film the feelings his characters have shed.) He flashes back to Henry’s childhood, but when in due course he returns us to the apparent moment of truth, Henry’s qualms turn out to be insubstantial.

By this time, though, Henry’s wife Karen (Lorraine Bracco), has started to tell her side of things. It’s unusual in this director’s films for a woman to have her say in voice-over, and if Scorsese had found a way to start the story in Henry’s voice and end it in Karen’s his film would have entered rewarding new territory. Karen is seduced in part by restaurant privileges. Here is a man who, when they go out on a date, doesn’t just get a good table near the stage – the waiters put up a whole new table for him in front of everyone else. When she learns what he really does for a living, she doesn’t recoil: “I gotta admit the truth. It turned me on.”

In GoodFellas, the women are fully guilty, though excluded from power. In fact the real rituals are all male: young Henry’s first court appearance, for instance, is celebrated by the gang as a loss of virginity. Scenes of all-male domesticity in jail, with the cooking duties fairly allocated (though of course it helps to have lobsters and fine wines delivered), are not parodies of family but the true Family.

Robert De Niro is reliably dynamic, and Joe Pesci’s portrait of a gangster with a sense of humour is hideously memorable, but there’s no doubt that GoodFellas fights a losing battle against numbness. Its comedy is too bleak to counteract the anaesthesia. Then near the end of the movie, Scorsese pulls off a terrific feat of film-making with a headlong account of Henry’s last day of freedom. Henry is drugged, frantic, barely in control, and on top of everything he’s cooking dinner, with no short cuts. By the sheer force of his direction Scorsese involves the viewer all over again with his worthless protagonist.

1991

Art

Tom Lubbock on conceptual art at the Whitechapel Open

It doesn't have to be the Whitechapel Open – it might be almost any contemporary mixed show, but it happens that in the Whitechapel Open this year, as indeed for many a year, there are a great deal of those pregnant, composite objects, those heady mixtures of household goods and industrial materials moulded into new and weird sensations.

Here are some. A block of wood, with a ledge around it, on which is hung a series of plastic disposable razors. A large aluminium object, resembling something from a ventilation system, with a black, woollen cosy over it.

A row of a dozen hammers, all over which are stuck rose thorns. A flat fish shape made of inner-tube rubber, attached to a foot pump, which looks as if it might inflate, but doesn’t. Here are some more: a group of gilded, Egyptian-style cats; a demijohn of home-brew; a board of transistors.

These examples, though telling, do not provide quite the whole range of this genre of quotidian exotica. Perhaps a hypothetical instance will be able to make the essential principles involved clearer.

Suppose you have been given an electric toaster for Christmas, and wish to increase its value by making some slight alteration to it. What might you do?

A: Exhibit the toaster plain and simple, with no alteration whatever. On balance, no. At any rate, not unless you are known to have worked with toasters for many years, in which case it may qualify as a gesture of radical simplicity which makes your previous output look positively baroque.

B: Use the toaster as a maquette, from which another toaster, 20 times the size, could be constructed. Though impressive, and simple in conception, this would be hideously expensive, require professional assistance, and might be seen anyway as somewhat vieux jeu. The point really is to think a little about the toaster, its form and function. Notice for a start that it has two slits in the top: potential orifices. Therefore, immediately:

C: Sexualise the toaster. Simply line (very neatly) its orifices with velvet, preferably red. A good combination, both in terms of sensations – metal against velvet – and also in terms of function. The toaster is now useless (so already more like a work of art), but more than that, it has become soft where it was most violent, though the red reminds one of heat, but is also fleshly. It retains, of course, an aura of functionality, but what in fact does this new object do? It is all fairly disturbing.

D: Make the toaster more dangerous by, for example, putting large spikes inside the openings. This is OK as far as it goes, but a little bit gratuitous; it thinks very little about the life and the character of the toaster, and how an element of animation, a life of its own, may be introduced.

Think more about function, and allow the machine to work. So:

E: Plug the toaster in, set it (but with nothing inside), and leave it on, having jammed the timer so that it doesn’t pop up (being careful to insulate the inside so that it doesn’t heat up too much). The element glows red. The viewer will need to peer into the machine to discover this – which becomes the discovery of the toaster’s secret passion, its burning heart inside the cool finish of its casing. It is the epitome of a dangerous domestic appliance. At the same time, from what we know of toasters, it urgently desires to pop up – but it can’t, its passion can find no release.

(You might also play around with heating element, making it into writing possibly, so that the words of desire glow red inside the toaster’s body.) Amazingly simple and effective. But deficient, perhaps, in self-reference. Hence:

F: The Toaster Toasted. Introduce it into a furnace and char it, just as if it were, as it were, a piece of toast. Or perhaps better: take about six toasters, and heat them up to different gradations of charredness, and place them in a row – one thinks of those beige-to-umber colour gradations found on some toasters. Thinking of that, one remembers that a toaster has a good deal of plastic in it, which would obviously melt.

It might be better to remove the plastic components before incineration, and refit them afterwards; this will give another agreeably weird effect. The plastic has miraculously survived, and it may remind the viewer of the phenomenon of spontaneous combustion, where the body is burnt, but the shoes (say) remain entirely undamaged. This covers the toasting side of the toaster, for the time being.

I’ve just thought of another one about frustrated function:

G: Remove the part of the toaster with the apertures in it, and replace it with an identical part, but which has no apertures in it, completely sealed – you may need to get an artisan to make this for you – a rather terrifying image of inhibited energy.

The relationship between toaster and bread may be developed further, by noticing that a toaster is, happily, almost exactly the same size and shape as a loaf of bread. This would suggest an interesting transposition:

H: Either, make an actual size replica of the toaster entirely from bread, or very much better, cut up the toaster thinly with a saw, so that it becomes sliced, just like a loaf; or again, just slice up half the toaster, and lie the slices next to it on a plate. Or again, simply but suggestively: place the toaster (unviolated) on a breadboard, with a bread knife lying by it.

We have so far neglected one essential aspect of the toaster, an aspect moreover which is enormously rich in implication. Namely, suspense. Whatever setting you put it on, you can never be sure when exactly it will pop up. So finally:

I: An event, performance, or time-based work. Take a great number of toasters, several hundred probably, and make some adjustments to the timing devices, so that they will pop up at regular/irregular intervals over a period of perhaps 10 hours. Fill the floor of a gallery with these prepared toasters. Insert bread in all the toasters, and set them. And watch. An hypnotic piece, involving all the senses. The sublimely mid-boggling quantity of toasters. The uncertainty of which toaster will deliver next. The anxious waiting, punctuated by the mundane anticlimax of toast delivered. The gradually increasing burntness of successive toasts, to the point of ashen disintegration. The very real danger of fire.

By this stage, a gesture of radical simplicity may be in order.

1992

Art

Andrew Graham-Dixon on Damien Hirst

There's no getting round the shark: a ton or so of pure killer instinct suspended, in perpetuity, inside a gigantic glass tank filled with formaldehyde solution. It was always going to steal the show devoted to “Young British Artists”, which opened last week at the Saatchi Gallery, and now it has done so. Its title is The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. But it is known, simply, as The Shark.

Rarely can a contemporary British sculpture (if that’s the right designation) have been so much discussed before it even existed. For some months now it has been widely known that Damien Hirst, the Great White Hope of British art, was working with a Great White Shark. (In fact, three days before he placed his order with an Australian fisherman, the Great White was declared an endangered species, so Hirst has had to settle for a Tiger Shark.) The Shark is rumoured to have cost Charles Saatchi more than £50,000, but the news from Boundary Road is that it was worth it. It will be remembered as one of the most remarkable British works of this, er, fin de siècle.

There will no doubt be those who wonder whether a real, dead shark, simply pickled in formaldehyde and placed on display, can justly be described as a work of art. Had it been commissioned by, say, the Tate, The Sun’s headline-writers would already have gone to work on it: £50,000 FOR FISH, WITHOUT CHIPS. But although The Shark might be hard to defend, that’s no reason not to try.

Hirst has adopted a classic strategy of Surreal, Dadaist and later modern art, which consists in the removal of something from its usual context (Marcel Duchamp did it with the urinal, Carl Andre with the brick) and its relocation within an art gallery. The tactic of displacement has been responsible for not just some of the major art of the century but, too, for a large quantity of lazy and uninteresting work. In an era that has seen an exponential increase in the number of such tired exercises in ‘“recontextualisation” – the Hayward’s Doubletake exhibition contains several examples – Hirst’s work represents a terrific reinvigoration of a near-moribund tradition.

The Shark is both scary and disconcerting, its range of effects genuinely surprising. The opacity of the glass used causes peculiar dislocations of vision as you circle the gape-mouthed carcass. Walking from its tail towards its head and rounding the corner of the tank to stare into its mouth, you find that the result of simultaneous refraction through two walls of glass makes The Shark’s head appear to lunge at you. This is not entirely pleasant.

Neither is it gratuitous, a mere special effect. The fact that The Shark appears to move contributes to its considerable power as an object of contemplation. It is a paradox made solid, this creature, at once frighteningly dynamic and completely still. It is, of course, a vanitas, albeit of an unusual kind: a work of art that prompts reflections on death, its inevitability, and our habit of avoiding that most unsavoury and basic fact of our existence.

It is an image of man’s power over nature, and its evocation of the exhibits in zoos or natural history museums is doubtless calculated. It demonstrates that even the most unreflectingly hostile animal can be transformed into, merely, matter for aesthetic consideration. The Shark will never break through that glass; we will never feel the impact of that awful row of teeth on our flesh.

But visitors to the exhibition tend to respond to its open maw with an answering grimace of their own, a grin that is not altogether complacent. This is appropriate, since The Shark is one of those rare works (and in this Hirst fulfils one of Francis Bacon’s desiderata for serious art) which operates primarily on the nervous system and only secondarily on the intellect. The uneasiness that The Shark provokes is related to its peculiar status as an image of human power – because it actually suggests how uneasy, how insecure that power really is. Hirst’s work comes to operate as a displaced image of our relationship to our own bodies, our ability to preserve the flesh but not the spirit, the form but not the life. The Shark, like the grinning skeletons earlier artists employed as their emblem of Death, might be said to have the last laugh.

1994

Dance

Judith Mackrell on Mark Morris’s L’Allegro, Il Penseroso e il moderato at the Edinburgh Festival

The overture, two movements from Handel’s Concerto Grosso in G, is performed with the curtain down. The first number, “Hence, loathed Melancholy”, is sung while the audience gazes at an unlit empty set – perhaps the “dark Cimmerian desert” to which L’Allegro, the happy or jolly man, would banish melancholy. Before we see any dancing, we are made to listen to Handel’s setting of Milton’s poetry.

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra, in excellent form, rose to the challenge of the spotlight. The conductor, Gareth Jones, went against prevailing fashion but his generous, unrushed tempos allowed Handel to sound meaty and left plenty of room for detail. Authentic or not, the orchestra proved convincing, and kept a forward momentum alive.

That beginning signals the respect choreographer Mark Morris has for the music. Later, when the smoky soprano Anne Dawson and the “full-voic’d choir”, Schola Cantorum of Edinburgh, sang of studious cloisters, “and a pealing organ sounded”, Morris had the dancers freeze: they, too, listened to the music. But Morris does more – his choreography illuminates the music.

Watching the dance doesn’t distract attention from the complex pleasures of listening to the music and the text, it adds to it: you hear more. Morris delights in literal, robustly nave illustrations that parallel Handel’s own delight in sound effect – in “Laughter holding both his sides”, for example, or in the soaring lark. So we see the full progress of the hunt, somehow we see the “Far-off Curfew sound... on a plat of rising ground”.

Elsewhere, Morris glosses Handel’s and Milton’s tribute to drama, when the male dancers alternate butch, cod-Shakespeare thigh-slapping with simpering, paired skipping.

There is mystery here, as well as reason, intelligence and musicality. I don’t know why the sight of two dancers spinning off into the wings as the stage darkens should have been so moving, but it was. By using the extreme edges of the stage, Morris appears to suggest that the dance we see is a fragment of an infinitely greater, larger-scale dance which occupies the wingspace, the entire theatre, the Southside, all of Edinburgh.

1995

Interview

John Walsh meets Barbara Taylor Bradford

THE phone rang three times in the Claridges suite during my chat with Barbara Taylor Bradford. Each time, she answered it with a gesture that had once seemed the quintessence of chic.

She swooped across the carpet like a practical-minded Valkyrie, seized the shrilling handset, tilted her magnificent head through 45 degrees and unsnapped a vast pearl-and-diamond earring as, in a single fluent gesture, her other hand applied the receiver to her fragrant, bijou-free ear. It took a moment to register that it’s just what Alexis Colby, played by Joan Collins, used to do in Dynasty.

Mrs Bradford – or “BTB” as she is invariably styled by her publishers, making her sound something between an illness and a company chairman – is often accused of living in a soap opera; more precisely, of living in the world delineated in her own novels, with their elegantly loaded, entrepreneurial dames and mahogany-complexioned husbands, their immaculately furnished living-rooms and stiffly implausible passions.

She can, of course, afford to be. The prima donna assoluta of modern female saga-writing, she is said to be the richest Englishwoman after the Queen, her personal fortune estimated at anything up to £625m. The combination of huge world sales, bogglesome advances (a three-book deal for £20m was negotiated with HarperCollins in 1992) and television rights to mini-series (the personal forte of her gravelly, Germanic husband Bob) brings wads of moolah in every post. Last year alone she netted £11.9m.

Her books have always been successful, beginning with the stratospherically best-selling A Woman of Substance, in which a kitchen maid called Emma Harte builds a global business empire with nothing more than Yorkshire grit and innate good taste.

The titles of subsequent books have harped on the concept of endeavour – Hold the Dream, To Be the Best, Act of Will, Everything to Gain – although their initial inspirational message of “You-too-can-run-IBM-while-remaining-true-to-yourself”, has matured into a more complacent, domestic murmuring.

Her later books feature, like a leitmotif, a woman of settled riches drifting through her gorgeous home noting with approval (“I’ve always loved this room”) the harmonious interior decor.

Their plots may lurch off into lurid murders, their walk-on characters may be the purest cardboard (Irishwomen will preface every remark with “to be sure”; the inhabitants of the Yorkshire dales are “canny, down-to-earth folk”), their conversations may lack any spark of interest or amusement, but those moments of heartfelt, Ideal Home self-congratulation ring with utter conviction.

Taxed with this judgment, the author bridles. “The books are about much more than that, and you know it. People are touched by the feelings and emotions in my books. Some say, you don’t have any mundane details about everyday life in your books, and I say, ‘No, because then nobody would read them’.” Her multitudinous fans, luckily, appreciate her for much more than literary style.

“People say, ‘You changed my life: when I read A Woman of Substance, I thought, if Emma can do it, so can I.’ A woman in Atlanta said something very nice to me: ‘My daughter is 18,’ she said, ‘and I told her, if you want to understand about love and sex, read Barbara Taylor Bradford’.” One feels that Atlanta will feature, in a year or two, a young woman comprehensively disillusioned about many things including coup de foudre love, male wooing techniques and the incidence of simultaneous orgasm.

It’s easy, and shockingly tempting, to ridicule Mrs Bradford, as she glides with designer-Dalek smoothness through a life of riches, fame and high connection. She wears her riches comparatively lightly, once you’ve got past the single-rope pearl necklace, the gold-and-emerald bangle, the huge diamond ring and telephone-defeating earrings.

When in London, she always stays in Claridges (a favourite setting in her books) because: “I like the decor and the restaurant. I’m a creature of habit. And I always stay at the Plaza Athénée in Paris because for months we lived there when Bob was running a film company in the Sixties.” Of course.

She hates shopping, though she may visit “Emma’s store” – which is Harrods, her first heroine’s emporium of choice – and Hermès, for its scarves and handbags. She likes to inspect galleries, especially Richard Green’s for the “French contemporary Impressionists” that she and Bob collect.

But amazingly she comes across, through all this, not as a monster of smug consumerism, but as a straight and rather sweet-natured person who has learnt some defensive, role-playing skills to fend off the outside world.

During our talk, she sat on a sofa with a velvet cushion clasped to her side, part comfort blanket, part bolster between herself and the smart-alec press. She’s a big, pretty woman of 62, with a volcanic, ash-blonde meringue of hair, merry eyes and a brilliant smile, and is not above flirting with her interrogator (“Did anybody ever tell you, you look like a young James Coburn?”).

She shares with her characters an endearing compulsion to explain things that require no explanation – that the Place Vendôme, where she got her blue frock, is pronounced “plaice” over here, but “plass” in Paris, that the art deco movement was in the 1920s…

1998

Theatre

Simon Callow on Falstaff

SIR John Falstaff has been widely described as Shakespeare’s greatest creation and his best-loved character, which in the circumstances is no mean claim. The adjective “Falstaffian” has long passed into the language. We all know what it means: fat and frolicsome, gloriously drunk, bawdy, boastful, mendacious; disgraceful but irresistible; above all, fun.

Not only, as he says in Henry IV Part Two, witty in himself, “but the cause that wit is in other men”, Falstaff provokes cascades of comparisons both from critics and from his fellow characters in the play; to see him is to be irresistibly impelled to describe him.

Because of all this, we feel we are familiar with the character, comfortable with him; we know who he is. It is easy to overlook how original and unprecedented a creation Falstaff is. There is no other character in Shakespeare to match him; no other character in Western literature, as far as I am aware, quite like him. There are braggarts, innumerable sots and reprobates galore: in the theatre alone there is the Miles Gloriosus, the bragging soldier of the Roman comedy of Terence and Plautus; mischievous rogues are a staple of the city comedies of Johnson and his contemporaries; and comedy, from Aristophanes to Terry Johnson, could scarcely survive without the drunkard.

There are even similar characters in Shakespeare: Parolles in All’s Well That Ends Well, Sir Toby Belch in Twelfth Night, elements of the Thersites of Troilus and Cressida. But even to mention these other characters is to affirm the uniqueness of Falstaff. In his never-failing wit, the abundance of his appetite and the bigness of his spirit, he contains – embodies, indeed – a life-force which is so overwhelming as to be beyond type, certainly beyond morality and even beyond psychology.

Above all, he is extraordinary in the two parts of Henry IV because of the relationship he has with the young Prince of Wales, soon to be the great warrior-king, Henry V.

Here is the 17-year-old heir apparently choosing to spend his life with a debauched, besotted, monstrously fat old reprobate in an East End brothel. It is as if the young Prince Charles had slipped away from Buckingham Palace to hang out with Francis Bacon – except that Falstaff is not only debauched, he is positively criminal: he and his dubious cronies beat people up in dark alleys and take purses from innocent travellers; and the young Prince Henry is no constitutional monarch’s son, he is the heir of the divinely anointed and absolute monarch, who in his very person is England.

What is going on, then? Is this mere truancy? Is the boy simply getting it out of his system, sowing his wild oats? Or is there something deeper going on? It seems there is.

It would be one thing if Hal were to have taken up the company of tarts and pimps, or to be slumming around with chums of his own age and class, in the manner of Darius Guppy and the young Earl Spencer. But it is quite another for the prince to have adopted this old scoundrel not merely as a friend but as a mentor, and to have extended to him every appearance of love and tenderness.

What do they want from each other, this odd couple? What Falstaff gets is, in a sense, obvious: the excitement of being so close to the heir to the throne, and the opportunity to practise his habitual lèse-majesté at the closest quarters; and the delight of being connected to youth, the most gilded youth of all, clearly has a tonic effect on the old rascal. But what does Hal want from him?

Alienated from his cold, anxious, controlling and guilt-ridden father, he has chosen Falstaff as a surrogate father, an antidote to the sterilised atmosphere of the court. He is liberated, relieved, made to think by this fallible, permissive, funny creature of animal warmth, who inverts the pieties and the truisms he has had dinned into him. It is with Falstaff that he discovers his humanity, the common touch which enables him to do what his father has never been able, to unify the kingdom and to reach out to his subjects in a way they can understand.

1999

Theatre

Paul Taylor writes about the suicide of the playwright Sarah Kane

The media called her “the Bad Girl of British Drama”, but my abiding memory of Sarah Kane, who at the age of 27 took her own life last Friday, is of a young woman delightfully doubled up in helpless, choking, gut-wrenching laughter as a group of us stood around cracking silly-foreigner jokes on alien soil. It was in Copenhagen last November.

A British delegation of dramatists, directors, theatre professionals (and this critic) had descended on the city for a weekend conference about the creation and nurturing of a new writing culture. The young woman who shot to notoriety and front-page prominence at the age of 23 with her Royal Court play Blasted, bided her time and stole the show at this event.

Playing up to an audience of eager, yet slightly chippy Danes, the Brit contingent had perhaps overstated the positiveness of the relationship between dramatist and theatrical establishment in this country.

Here was the cue for Kane, in the evening session, to cut the self-congratulatory cant and launch a devastating account of the innumerable ways in which a writer’s vision is often, and for institutionalised reasons, betrayed in this world mecca of theatre. The Danes lapped her up.

Afterwards, with everyone a bit hysterical from a gruelling 14-hour day, we drank too much and started poking fun at the (to our ears) supreme absurdities of the Danish tongue where, say, the word for “bookshop” is “boghandel”.

My first thought that night was: how can one square the spectacle of this slight, fresh-faced blonde woman, creasing herself in schoolgirlish laughter, with the dark extremities of the dramatist’s imagination that has put on stage every atrocity from the eating of dead babies to forcible sex-changes in totalitarian prisons; from violent male rape to castration and a mutilated penis sizzling on a barbecue?

My second thought was: no, somewhat frighteningly, this adds up. The life-loving elation was the flip side of the depression that did, indeed, eventually push her to the brink and beyond.

So, it’s the laughter I remember: but in her short professional life, it has to be said there wasn’t a great deal for her to laugh about. Blasted, the play in which Bosnia suddenly erupted into a Leeds hotel room, can be seen as both the making and the unmaking of her.

Not many 23-year-old dramatists wake up to find their latest work the subject of heated discussions on Newsnight, or dismissed as “a disgusting piece of filth” by the Daily Mail, or hailed as the most auspicious Royal Court play since Edward Bond’s Sixties masterpiece Saved.

After a suicide, it is only human to grope for something – or preferably someone -– to blame. It is a temptation that should be resisted. In the following days, there will, doubtless, be cheap journalistic exercises in breast-beating hindsight, alongside the suggestion that, given her mental fragility and the media feeding-frenzy that tended to accompany her every play, the suicide was a tragic accident waiting to happen.

The truth is more complicated and humdrum. It’s certainly the case that very few journalists come out well from the Blasted brouhaha – not least this critic. Not only were the reviews almost unanimously hostile, but the play provoked an astonishing level of moral outrage which spread to the news pages.

Of course, in all the resulting fog of whipped-up synthetic indignation, the play – which both exhibits precocious talent and is obscurely flawed – never received the kind of sustained analysis it deserves.

It is a drama in which the central character (like Kane’s own father) is a tabloid journalist and, among many other things, Blasted is an indictment of the priorities of tabloid journalism. Ironically, the reception of this work endorsed her cultural diagnosis. Thought was abandoned: instead, the press gave Kane the “Bad Girl” label and left her with the impossible dilemma of living up to it – and living it down.

It’s perhaps no accident that, just as her friend Mark Ravenhill followed up Shopping and Fucking with a contemporary reworking of the Faust legend, Kane moved after Blasted into the relatively less exposed area of classical updates.

But Phaedra’s Love is, I sense, a very personal work. The ache to find something redemptive and tender in a godless, loveless universe (crucially, Kane was a lapsed born-again Christian), here becomes more insistent. The play’s most piercing stroke is Kane’s radical solution to the tricky problem of finding a modern-day counterpart for the proud young prince, Hippolytus, who spurned his stepmother’s amatory overtures with a priggish, militant chastity.

In her version, he becomes a grungy, reclusive, Nineties slob whose denial of love is expressed not as celibacy but as the indiscriminate indulgence of someone who treats sex as junk food and crap TV. He idly allows Phaedra to give him a blow-job, which cruelly highlights the fact that while it’s easy to get into this guy’s knickers, it’s impossible to get into his heart.

Kane’s last two works pushed two divergent extremes: visual and verbal. Cleansed was like a cross between a play and an installation piece as it evoked an unremittingly harrowing institution designed to rid society of its undesirables. For the first time here, in my estimation, the yearning for some loving, purifying alternative to the horror, symbolised in the incestuous devotion between a brother and sister, made a deeper dramatic impact in a Kane play than the atrocities.

I suspect, though, that on these deep issues she was incapable of the consolations of self-deception. Sarah Kane was a moralist of sometimes rebarbative rigour and mordant wit. A terrible pity that her career, which began with a storm of publicity, looks set to end in the same way. We all, press and theatre included, need to take far greater care of young talent and to remember that, as Ezra Pound put it, art is news that stays news. But, if the ending is grievously premature it also, like her writing, demonstrates an unselfsparing logic and, yes, considerable strength of character.

2000

Musicals

Oklahomo! David Benedict on why gays like musicals

AT A dangerously impressionable age – about 11 – I saw Funny Girl at the now defunct Waldorf Cinema in Basingstoke with my friend Liz. It was a momentous occasion. During that film I underwent my heterosexual phase. Feeling it was expected of me, I put my arm around her. Sadly, close questioning has revealed that although she remembers seeing the film together, my advances are forgotten. Nonetheless, this occasion marked the onset of the first stage of my psychosexual development: my real object of desire was, of course, Barbra. I was in the state of Oklahomosexuality.

The moment sound arrived in the movies, studios began making musicals. And from that moment on, lesbians and gays have been singing the songs and dreaming. I realise now that I didn’t just want to watch Barbra; on some level I wanted to be her.

The physical manifestation of this pre-gay stage consisted of dancing around the living room miming to records and dreaming of a career (preferably hers) in musicals. It is risky to generalise, but I know I was not alone in this.

Close identification with musical stars – usually female – is hardly the sole preserve of shy boys growing up in the Sixties in Hampshire. Following that initial manifestation, there is a more mature developmental stage to Oklahomosexuality. At some point, usually when falling in lust and/or love, you realise that Streisand’s career is perfectly safe and you are, in fact, merely gay.

Nevertheless, in my closeted years, it is significant that my love of musicals was an equally closeted passion. Only after coming out did I stop being embarrassed by so obvious a giveaway as owning more original cast albums and Streisand LPs than was strictly necessary.

So what is it about musicals that makes them “gay”? After all, heterosexuals have been known to watch them. Even male heterosexuals. There simply aren’t enough queens in the world to account for the viewing figures of The Sound of Music.

If it were only gay men who thrilled to the form, why would Twentieth Century Fox have bothered to sign up Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell – two of the world’s most legendary pin-ups – for Gentlemen Prefer Blondes?

Yet you don’t have to be a semiotics student to watch that musical and realise that something’s going on. For proof, try the gym sequence, in which Jane Russell, a famously big girl, wears not a lot and sings “Ain’t There Anyone Here For Love?”. There she is, a panther in a swimsuit, prowling, preening and leaping into the pool with hundreds of men dressed in nothing but shorts and smiles who don’t give her a second glance.

In 2000, that scene looks knowing to the nth degree. But it was shot in 1953 when, in the words of the critic Vito Russo, “As far as American cinema was concerned, homosexuality was something you did in Europe or in the dark. Preferably both.”

Permitted images were scarce. Non-musical films were hidebound by the conventions of realism which traditionally provided us with images of pain and despair. The unofficial but ruthlessly upheld guidelines for gay men were characters who either flapped their wrists or slit them.

Lesbians – usually murderous or just plain miserable – were even thinner on the ground. In the post-liberation era, those ninnies and nancies, predatory sloe-eyed vamps and diesel dykes are re-viewed with ironic affection – a kind of “look back in angora” – but in times when we were starved of positive images and desperate for a route out of invisibility, these creatures were hardly the stuff of our wildest dreams.

So generations of movie-going lesbians and gay men became eagle-eyed about spotting subtextual hints and winks. When it comes to musicals, straight men argue that they can’t see the point – which is the whole point.

Musicals are unique teaching tools. Disaster movies such as Airplane! may teach us how to fly a plane with a divorcing couple, a kid on life-support and a singing nun on board but when it comes to our sentimental education, every other genre from Westerns to screwball, from action pictures to three-handkerchief weepies, fades into the background.

2001

Film

Charlotte O’Sullivan on Bridget Jones’s Diary

IT’S a truth universally acknowledged that Jane Austen had a great way with an opening sentence. Less widely accepted, but equally pertinent, is the fact that she had the “feelgood” factor down to a fine art. So it really isn’t anyone’s fault but hers that Bridget Jones’s Diary – based on Helen Fielding’s louche retelling of Pride and Prejudice – is a tad short on suspense.

From the minute that our ditzy PR heroine makes a twit of herself, and ace barrister Darcy (Colin Firth) looks intently at her across a crowded book launch, you know He is the one for Her. Only one ending will do: Bridget left scribbling all alone? Bridget shacked up with Daniel (Hugh Grant), her unreliable, anal-sex-loving boss? What do you think this is – Chinatown?

Luckily, not everything about the film is so ho-hum, including the appearance of the American interloper herself, Renée Zellweger, who famously piled on the pounds to play Bridge. You literally can’t take your eyes off her.

With those prairie cheeks (the hairs on her skin look like cropped corn), that potato-blonde hair, and a way of moving through perfectly ordinary space as if she’s being herded through a field, this woman couldn’t be more natural, or vulnerable. Her plentiful flesh squished into industrial-strength knickers and tight bras (even in bed), she’s struggling in a world that wants sharp urban lines. Primed by years of cinema-going for the Pygmalion-esque “transformation” scene, you actually wait for the double chin to melt away. It doesn’t.

Zellweger has always had it in her, of course. In the Farrelly Brothers’ gross-out comedy Me, Myself and Irene, her character admits that when her modelling dreams went sour, “I got this eating disorder where I gained, like, 20 pounds... in a week.” Or, as Hank, the cad in her life, puts it, “the only bright light you saw were the ones that hit you in the face when you opened the fridge”.

The difference is that this appetite is now on display and – surprise, surprise – Variety has already blamed the director Sharon Maguire and her crew for “going a bit too far in making [Zellweger] look unattractive”. They take issue with Rachel Fleming’s costumes, too. True, Bridget’s outfits all look like things that have been hanging in a wardrobe for years, but that’s what’s so liberating. She even wears cardies from French Connection. How’s that for cinéma-vérité?

Given that Zellweger still looks lovely by normal standards, it just goes to show that in show business, “normal” equals unattractive. Last year’s High Fidelity put the case most clearly: in Nick Hornby’s novel, the hero’s gripe with his girlfriend is that she, like him, is so “ordinary”; in the film – hey presto! – she’s a stunning, immaculately dressed blonde.

That Zellweger can make us believe in Bridget’s heaving inner world is par for the course – she’s a supremely talented comic actress. That she was willing to risk her own status as sex symbol by looking like an everywoman is really impressive.

Another shock is the liveliness of the writing. Working Title’s previous hits, Four Weddings... and Notting Hill, relied on slapstick, plus the words “fuck” and Billy Bunterisms like “crikey”. The revised team – Richard Curtis, Helen Fielding, Andrew Davies – still lean heavily on all three, but have come up with a procession of bright one-liners, too.

It’s a neat touch that when, at the book-launch, super-suave Daniel has the chance to dance the verbal fandango with Salman Rushdie, he stammers “Er, do you know where the loos are?”. Five minutes before, Jones said just the same thing and at a stroke, it becomes clear why she adores him – faced with a choice between fight or flight, he plumps as desperately for the latter as she.

Such scenes owe everything to the great American sitcoms, though not the ones you might think. Bridget, it turns out, has less in common with brittle-skittle Ally McBeal or the pouty women in Sex and the City than Seventies klutz Rhoda or the fubsy Seinfeld crew.

Asked by a “smug married” why so many women over 30 have trouble getting a man, Bridget replies: “I suppose it doesn’t help that beneath our clothes, our entire bodies are covered in scales” – a line that could easily have emerged from Elaine’s caustic New York kisser. Or, if the question had concerned the lack of options for tubby men with glasses, that of George. Forget women versus men, think underdogs versus the rest.

2008

Pop

Andy Gill on ‘Why I hate Coldplay’

WITHOUT wanting for a moment to give the impression that it’s anything other than a wonderful way to earn a living, there are times in a rock critic’s life when the soul sighs, and one faces the blank screen with heavy heart and empty head. Last week was one such time. A new Coldplay album.

When, all too frequently, people say how great it must be to earn one’s corn writing about music, it’s hard to disabuse them of that opinion. Of course it’s great! But I tend to offer one small caveat: it’s not just writing about music that you enjoy – often, duty makes demands beyond one’s personal tastes. And while experience, or low cunning, might spare one unnecessary exposure to the reviewer’s less vital duties – sometimes an act is so huge, so current, that it’s impossible to ignore their enervating new release. A new Coldplay album.

“Well, at least I’m not dodging sniper bullets in Helmand,” you tell yourself, and set about the task in hand, knowing it’s going to be no more rewarding an experience than the last time you deliberately exposed yourself to their mawkish stadium-rock anthems. Though actually, who knows? After all, this one’s produced by Brian Eno, and he even managed to make U2 bearable for an album or two.

In the event, the album is almost exactly as I expected, if a tad shorter on Big Anthems than the previous three. The rhythms are a bit busier, and a bit more ethnic, and Chris Martin’s little falsetto catch – one of modern music’s most irritating tropes – has been rationed out more parsimoniously. (Thanks, Eno!) And in a few cases, the songs do seem to be about things, rather than just anaemic expressions of emotional indulgence and limp consolation, like X & Y. Things like death, and war, and power. It’s… not much, really, but not so little as to be completely worthless. It’s the new Gold Standard of Average Music. And given the competition currently battling for that dubious honour, this is no mean feat. Almost an achievement, in fact.

But don’t just take my word for it. Tomorrow you can buy the album and hear for yourself – as will untold millions around the globe. Viva La Vida has already broken the record for iTune’s biggest album presale, and will doubtless repeat the success of X & Y, which reached No 1 in all 15 territories surveyed in Wikipedia’s comparative chart, and shifted upwards of 10m units.

The strange thing is, I can’t seem to find anyone who bought X & Y, or who intends to buy Viva La Vida. For that matter, I have never encountered one person who has a kind word to say about Coldplay. None of my personal or professional acquaintances, nobody in the street or the local café, not a single soul will admit to liking Coldplay or purchasing their music. Indeed, most seem to agree that they epitomise everything that’s wrong with modern rock music. So who’s buying all their albums? Who are those masses politely arrayed in their thousands at stadiums when Coldplay play? Is it some secret society, an Opus Dei of dreary anthemic music? And where do they congregate, other than at stadiums and arenas? Do they have parties?

Yes, yes, I know, I shouldn’t be so hard on them – they have it hard enough already. But it does seem to be the case that Coldplay have become one of those definitive cultural dividers, the twain of which shall never meet. They’re sort of the anti-Sex Pistols, an act that repulses not through outrage, bad manners and poor grooming, but through their inoffensive niceness and emollient personableness. In 1977, EMI couldn’t divest themselves of the troublesome Pistols quick enough, you might recall; but in February 2005, that same corporation’s whopping share-price fall of 46.25p (to £2.35) was largely attributed to the announcement that X & Y would not be released during that fiscal year, as originally expected.

This corporate impact is especially ironic given Martin’s highly publicised advocacy of anti-corporate, pro-Fair Trade principles, just one of several ways in which the band offers a pale reflection of their most obvious influence, Radiohead.Their music sounds like Radiohead with all the spiky, difficult, interesting bits boiled out of it, resulting in something with the sonic consistency of wilted spinach.

Another obvious comparison would be with Pink Floyd: they evoke much the same oceanic sense of unease and uplift, and employ the same type of widescreen arrangements, though as with their Radiohead influence, there’s little hint that Coldplay share the Floyd’s questing artistic temperament. Nor could they emulate the distinctive lyrical approaches of Yorke or Roger Waters, both of whose work is simply too acerbic and bitter, and frequently too twisted and ambivalent, for such innate populists to handle. So what Coldplay invariably fall back on is the disingenuous empathy of lines like, “Is there anybody out there who is lost and hurt and lonely, too?” and “Are you lost or incomplete... can’t find your missing piece?”, lines feeding off the soul-carrion of the insecure and lonely while offering no solutions.

Songs like “Trouble”, from their debut album Parachutes, and “In My Place”, from A Rush of Blood to the Head, are anthems of amorphous yearning designed to be as widely applicable as possible; all-purpose wallows whose self-pitying, apologetic tone sounds utterly bogus.

By 2005’s X & Y, the band had shifted slightly from outright self-pity to broader misgivings, a move marked by the shift from first-person to second-person in songs like “Fix You” and “A Message”, cunningly enlisting their audience as co-mopers through songs of solace articulating vague, windy concerns – “I’m scared about the future and I want to talk to you”, “When you feel so tired and you can’t sleep/Stuck in reverse”, etc – invariably resolved in mealy-mouthed platitudes like “I will try to fix you” and “You don’t have to be alone”.

There’s no real sense of grappling with the social or political causes of the problems, just a bland emotional poultice applied to the wound. They’ve become the sonic security-blanket for millions of fans, their tracks sweeping by with the epic solemnity of state funerals, their huge, heartbreaking chord changes sucker-punching you with emotional logic while sapping any anger or political engagement that you might otherwise experience. Instead, Chris Martin offers a consoling arm around the shoulder and a nice cup of tea. But rarely can a claim have been less borne out by circumstance than “I will fix you”: with Coldplay, it’s never more than cold comfort.

2010

Theatre

Paul Taylor reviews Jerusalem

Last year, illness kept me out of the theatre for nine months. Human beings are stubbornly stoical creatures and it was surprising just how bearable I found being absent from some of the hits of the hour. But the one thing it’s fair to say that I pined to see has just obliged me by transferring to the West End and it’s been worth the wait. Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem, beautifully directed by Ian Rickson and starring the incomparable Mark Rylance, proves to be, if anything, even better than its award-laden, ecstatic publicity suggests.

Rylance plays Johnny “Rooster” Byron, the frowsty, vodka-swilling ex-stuntman; the chaotically unholy mix of Falstaff and Pistol; the drug-dispensing misleader of youth who makes Socrates and the Pied Piper look like Maria von Trapp; the limping hangover-waiting-to-happen; and the one-man caravan-dwelling challenge to everything in our current nannying, amnesiac culture that wants to pave over the past and chain us in our nappies to focus-group-fostered conformities.

Set on the annual St George’s Day Flintlock Fair, Butterworth’s play is liberatingly funny and doubly subversive because it constitutes both a celebration of the ancient rituals of this green and pleasant land and a droll acknowledgement that many supposedly immemorial traditions were invented by authority relatively recently in an effort to put one past the people.

Facing eviction from his gypsy redoubt by South Wiltshire Constabulary, Johnny may be an inveterate fantasist and an incorrigible self-mythologiser but he knows how to call the bluff on crappy cant. Wesley, the publican, has been forced by the brewery (“a Swindon-level decision”) into Morris-dancer clobber so that, as the “Barley sword-bearer” he can enact an alcoholic-cake-cutting ritual that “connotes fertility and the hunt”. Johnny takes one look at a cack-footed excerpt and lobs this little hand-grenade at it: “I’m no expert, but to me it says, ‘I have completely lost my self-respect’”.

Rylance creates the illusion that he has physically reinvented himself to play this tough-bodied broken-boned figure. But he’s so in tune with the spirit of the role that it is as if he has co-created the character with Butterworth. Our greatest living actor may never have misled male minors or seduced underage girls; but he once led a tour of The Tempest to ancient sites built on England’s ley-lines and he brilliantly resurrected the ethos of Shakespeare’s Globe, and he’s never been unwilling to disturb the smooth hypocrisies of an awards ceremony with pointed political protest.

Rickson’s cast are uniformly superb in all their cranky idiosyncrasies. But Rylance is, like Johnny, in a league of his own. Aptly for a play about the layers of tradition, his performance seems to strike retrospective probes through his career to date – right down to another seditious outlaw who headed a gang of misfits: Peter Pan. You even get a smack of a cracked version of Henry V when our drug-fuelled hero imagines his band of brothers taking on the local council.

It’s a wonderfully funny feat, shadowed by darkness. Just watch the mixture of oblivious child-like wonder and adult denial with which he stares at the mobile phone playing footage of him drunkenly smashing his own TV with a cricket bat. As he recounts his tall tales of meeting giants, he’s brilliantly elusive – part transparent con and part infectiously convinced by his own, often bathetically chatty legend. And unlike Falstaff, Johnny is not at bottom a coward. Alone as he always knew he’d be, Rylance makes you root fiercely for this unorthodox, instantly iconic hero as he pounds the drum and invokes at the end. The other noise you hear is the sound of the audience’s hearts beating in fervent response.

2012

Culture

Tom Sutcliffe on William Hogarth and Martin Amis

Which did Hogarth enjoy drawing more – Gin Lane or Beer Street? Or to put it a different way, which panel do you think he drew first?

Which part of that famous double image was the fun bit and which the follow-up spadework, required to make the moral contrast work? It’s really not a difficult one this, I think. You just have to ask yourself where your own eye first travels. And it seems obvious to me that it’s to Gin Lane, with its vista of human depravity. In Beer Street, everything – apart from the pawnbroker down on his luck – is seemly and meet. It’s a scene of industry and plenty. And it’s just a bit dull. By contrast, Gin Lane is a vision of moral ruin. And yet that’s the picture we’re drawn to and – surely – the picture that Hogarth most relished working on.

I found myself thinking about this while reading Lionel Asbo, Martin Amis’s latest novel. He has suggested that it is a Dickensian exercise in social observation (or at least that Dickens was his admired model). But it is also quite Hogarthian in some ways – a doubled study of divergent fates rather in the manner of Hogarth’s didactic series Industry and Idleness, which contrast the fate of two different apprentices. In Amis’s case, the industrious apprentice is Desmond Pepperdine, a young orphan who raises himself by reading, and the idle ‘prentice is his Uncle Lionel – an inner-city grotesque who at one point explicitly excoriates the idea of learning anything in life.

And if you ask yourself a similar question about Amis and the creation of his novel – which character did he enjoy writing more? – I think you come up with a similar answer. Desmond may be the moral centre of the book, the character who gives it heart, but you’re never sorry when Lionel lurches into the room, steam rising gently from his swart body. And though this might be the projection of a reader’s interest, I think Amis’s prose also brightens when he arrives. It isn’t really surprising. Just as Hogarth would have sensed the difference between drawing a conventionally pretty housemaid in Beer Lane and the gin-addled slattern who visually echoes her, Amis responds to the greater liberty for invention. Beauty has its rules and its conventions. Ugliness – moral or physical – takes off the brakes.

Any caricaturist, of course, has a professional dependency on the grotesque. As one latter-day Hogarthian, the cartoonist Martin Rowson, put it when I asked him about the issue: “All satirists are there to lower the tone.” He also confirmed the tendency for caricaturists to become infatuated with their monsters.

But Amis’s difficulty with this effect in his novel is rather different to that of Hogarth, I think, because it undermines the very moral case he is making. You can be fascinated by Hogarth’s vision of drunken fecklessness without being drunk and out of it yourself. The mind probes the jagged edge of the worst thing imaginable – dropping your baby to its death – but you are never really implicated in that atrocious loss of control.

That’s less true of Lionel Asbo. The book is partly about the perversion of values that holds celebrity (and notoriety) at a higher price than actual achievement. But it also effectively requires us to respond with a tabloid reader’s avidity for base gossip. What keeps us reading is the desire for something worse to happen, for the story to take a darker twist. Without giving anything away, I think Amis’s plot eventually rebukes that appetite in us. But his book wouldn’t work at all if it didn’t feed it first. He implicitly asks, in dismayed tones, why it is that we’ve become so obsessed with the badly behaved and the self-indulgent. And he answers the question with his monstrous hero.

2013

Books

Boyd Tonkin reviews Morrissey’s Autobiography

A Penguin Classic? Not in a month of rainy Mancunian Sundays. Let’s hope that Penguin’s suicidally foolhardy executives wake up howling once they realise that the publisher’s (until now) best-loved and most carefully curated brand sports a title stuffed with sentences such as “I appear to be more well known in Mexico than even in Sweden, Peru or Chile.” This from an author whose idea of literary criticism is to sneer at “the swill-bucket of British poetry” and claim that the Poet Laureate is chosen “to loud yawns of national disinterest”.

Whatever Penguin’s motives in debauching its list with this book, “disinterest” (in the correct sense of the word) certainly does not rank among them. And yet… for 70 or 80 pages, perhaps for 150 (out of a patience-taxing 457), a properly disinterested observer could nurture the hope that Steven Patrick Morrissey will make good on the promise of 25 years of achingly melancholy lyrics with a memoir that might stand the test of time. For a while I wondered whether I would have to, gratefully, eat my previous words condemning Penguin – perhaps with curry sauce and mushy peas.

“My childhood is streets upon streets upon streets. Streets to define you and streets to confine you,” in a perpetually dark Victorian Manchester, “the old fire wheezing its last.” The dank, bruised world of The Smiths’ songs, and of Morrissey’s earlier solo albums, acquires depth of field, narrative momentum, the tenderly remembered loves and quirks of his Irish family. Anthony Burgess, another Mancunian Catholic, comes to mind. The “hidden injuries of class” (Richard Sennett’s phrase); the consolations of pop, films, TV; the Gothic melodrama of school that explodes in “the topsy-turveydom of 1972”, with Bowie, Bolan and the New York Dolls: for almost a quarter of Autobiography, I did sniff a potential Modern Classic in the making. Even the slightly pedantic interlude on his poetic idols – Oscar Wilde (naturally), also Housman, Auden, Betjeman – anchor his lyrical gift in a patchwork personal tradition that somehow comes together and makes sense.

With the arrival of Johnny Marr, the descent of the Sex Pistols on the Free Trade Hall in 1976 and the first hits with The Smiths, a more conventional narrative of fame kicks in, with its few blessings and (inevitably, given the author) many curses. Worse, the predictable whine of self-pity and self-justification begins to rise in volume.

For a while, this can be fun: Wilde’s fate prompts the first of many furious lunges at judges, courts and the British legal system. And when Morrissey stands back to consider what he has created, the skies darken, the rain lashes, but the heart warms: “It would be the ache of love sought, and not found; buttoning your overcoat as you stand before an ash-slag fire as you ponder years of wasted devotion… It would be the north of England.”

Alas – and here Penguin’s complete abdication of authority comes to the fore – such passages recede. An editor with nous and guts could probably carve a “classic” 200-page testimony of northern upbringing and early music-business days from this material. Look at Patti Smith’s Just Kids to see how it could and should be done.

Sadly, here the superstar’s puerile litany of grievances eventually takes centre-stage. It reaches its numbing culmination in 50 deadly pages on the 1996 court case over royalties allegedly owed to former band member Mike Joyce.

The droning narcissism of the later stages – enlivened by the occasional flick-knife twist of character sketch, or character assassination (watch out, Julie Burchill) – may harm his name a little. It ruins that of his publisher. For the stretches in which in his brooding, vulnerable, stricken voice uncoils, particularly across his Mancunian youth, Morrissey will survive his unearned elevation. I doubt that the reputation of Penguin Classics will.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies