New York Times publishes treasure trove of American food

From chilled corn soup to key lime pie, Christopher Hirst cooks the book

If anyone thinks that my production of a cheesecake sounds a bit girly, I suggest that they take up that point with such tough nuts as Harry the Horse, Little Isidore and Dave the Dude. Lacking such fripperies as a fruity top and a biscuity base, this zesty creation is the cheesecake that repeatedly appears in the hard-boiled humour of Damon Runyon. The guys and dolls in his Broadway yarns are constantly visiting a deli called Mindy's for a slice of cheesecake. This was actually a joint at 1655 Broadway called Lindy's (deceased 1969).

The pastry chef moved on to Las Vegas, where the cheesecake continued to wow the clientele. Though he refused to reveal the recipe, his boss worked it out from the ingredients that the chef ordered and the number of cheesecakes he produced. The resulting recipe was published in The New York Times in 1977. Magically contriving to be simultaneously light and creamy and sweet and savoury, my rendition drew applause at the end of a Sunday lunch. Even Dave the Dude ("certainly not a man to have sored up at you") might have expressed admiration. Though the ingredients came from a south London supermarket, the result was pure New York.

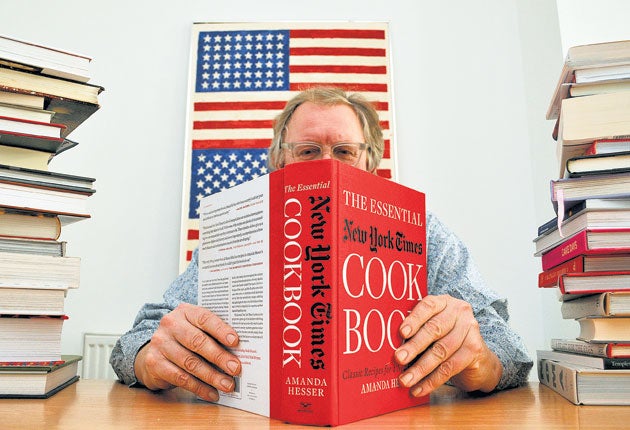

Lindy's cheesecake appears on page 757 of The Essential New York Times Cook Book (Norton, £30) by Amanda Hesser, a former food editor on the paper who disinterred 1,400 recipes from its files. She cooked her way through all of them and selected 1,400 on the simple criterion "Would I make them again?" The result is this whopping tome. Quite a few recipes were contributed by Hesser, who gives the winning excuse, "because there was no-one to stop me". Exuding the energy, pizzazz and sheer foodiness of the Big Apple, it is for my money the most tempting, relishable and all-encompassing food book published since Alan Davidson's glorious Oxford Companion to Food.

It is also very funny. Of a dish called Oliver Clark's meat loaf, Hesser says, "This recipe seems to have been written by a mad chemist or a mouse, with tiny pinches of this and that." Pondering chilled corn soup, she erupts, "You want me to use another Goddamn pan!" Describing a recipe for spaghetti primavera from the ritzy La Cirque restaurant, she encourages readers to go through "all 12 pain-in-the-neck steps of it... because it's wonderful."

Despite the problem of converting American cups to millilitres and ounces to grams (not too difficult and anyway it's good for the brain), Hesser's haul from the past 150 years is packed with interest for any lover of Americana. We encounter such intriguing items as hoppin' John ("a family of rice and pea recipes"), country cousin (a chicken and green pepper dish favoured by Franklin Delano Roosevelt), heavenly hots (a "feathery" pancake) and cherry and coconut Betty Brown ("it relies on nothing more than bread crumbs and sugar for its infrastructure").

On page 742, you'll find a recipe for a dish that provided the startling simile in Raymond Chandler's Farewell My Lovely: "He looked as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a slice of angel food cake." Other stateside classics include Boston baked beans ("I'm including this dish not because it's so amazing – although it is pretty great – but because it's so different from baked beans as we know them"), key lime pie, succotash (the bean, corn and cream dish used as an expletive by Sylvester in Looney Tunes) and North Carolina pulled pork. I once tasted this melting southern treat in situ and was pleasingly surprised by the accompanying vinegar sauce, which cut the fattiness of the slow-grilled meat.

In 1949 General Eisenhower gave the paper a recipe called steak in the fire, which is exactly that. Requiring a "four-inch thick sirloin", the reader is required to "nudge it over once or twice but let it lie in the fire [a pile of glowing charcoal] for 35 minutes". Explaining the infrequency of recipes from that decade, Hesser writes: "I am saving you from a world of hurt."

Though Britain is still widely regarded in the US as the world's greatest repository of terrible food, she makes amends by including Jamie's pumpkin risotto, Nigella's Italian roast potatoes, Fergus Henderson's roasted marrow bones and Anton Mossiman's braised Brussels sprouts in cream. Hesser also includes Welsh rarebit ("surprisingly under-appreciated here in the land of grilled cheese"), though her shepherd's pie goes way off-beam by a) being curried and b) using beef (lamb is usually regarded as "ethnic food" is the land of the free). She should also know that the delicious potato dish Janson's Temptation should be made with Swedish anchovies (actually a kind of brined sprat). Her nearest branch of Ikea is at 1 Beard Street, Brooklyn.

For the most part, however, you turn the pages murmuring, "I want to eat that and that and that..." From sea bass in grappa ("my no-stress dinner party standby"), you move on to Alain Ducasse's "fantastically delicious" halibut in parchment, Elizabeth Frink's (yes, our sculptor) super-citric roast lemon chicken and the minimalist gravadlax ("almost no effort") from New York Times stalwart Mark Bittman. He was the first to publish the recipe for the world-sweeping no-knead bread, which appears on page 670.

Hesser's simplest recipes may just be her most valuable. These include "a perfect batch of rice" and French fries, though I'm particularly drawn to homemade butter: "Oh, it is extraordinary." I'm tempted by pickled watermelon rind ("like mace to nutmeg"), the Italian beef stew that Hesser "would happily make once a week" and spoon lamb ("possibly the best recipe title ever"), though something called bacon explosion may be beyond my capacities: "Very carefully separate the front edge of the sausage layer from the bacon weave and roll the sausage into a compact log."

The dish that drew me into the kitchen was pear upside-down cake. "Sometimes you read a recipe title and immediately you have a clear picture in your head of how it will turn out," writes Hesser. "And sometimes you're way off, as I was here." She was expecting something "light and buttery". The reality, as I deliciously discovered, is dark, spicy and unctuous. It reminded me of the Yorkshire gingerbread called parkin – though containing six tablespoons of poire Williams, it is a distinctly plutocratic relative. The crunchy, slightly gritty taste of the cooked pears, which (of course) appear at the top of the cake, marry magnificently with the molasses-rich, alcohol-laden texture.

A few recipes are non-runners for the British. Sadly that great New York treat of shad roe (which makes a salacious appearance in Cole Porter's "Let's Do It") is off the menu for us. Same goes for the handful of recipes including corn syrup (Hesser's suggested substitutions of brown rice syrup and agave nectar don't help much). Still, there are almost a thousand others to go at. Such as green pea fritters from 1876, which is really a savoury drop scone that will go nicely with smoked salmon spread. And the Nicky Finn cocktail: two parts fresh lemon juice to one part brandy and one part Cointreau with a hint of Pernod. Shake with ice. I bet Dave the Dude would like that as well.

Lindy's cheesecake

3tbsp wholemeal biscuits crumbs

four 200g packets of cream cheese

grated zest of 2 lemons and 1 orange

1tsp vanilla extract

125ml double cream

180g sugar

4 large eggs

2tbsp crème fraîche

Heat oven to 190C. Butter a deep, 8in- diameter pan (either springform or silicone), sprinkle crumbs inside and shake out excess. Using mixer at low-medium speed (or bowl and hand whisk) whisk cream cheese, grated zests and vanilla. Add double cream and sugar, then one egg at a time. Beat well after each egg. Beat in crème fraîche. Pour mixture into prepared pan. Set pan in a larger pan or oven tray and pour boiling water around it. Place in oven and bake for 75 minutes or until centre does not quiver when pan is shaken. Remove from water bath and stand on a rack for at least 10 minutes. Invert onto a plate and unmould. Hesser says this should be done "while hot," but I left it overnight and the cheesecake emerged intact from the silicone pan. It should be creamy-yellow with brown blotches and the lightest mottling of biscuit crumbs. Resist the temptation to add any topping. By warming your knife in warm water (and drying), you'll get clean edges to your slices.

Big and beefy

The Essential New York Times Cook Book is the latest in a long tradition of giant food books. Though you may not eat all their contents, these paving-stone-sized volumes will certainly eat up your shelf-space.

Running to 1,200 pages, Larousse Gastronomique (£60) remains the best guide to the world's greatest cuisine. Though the latest edition has brief entries on Heston Blumenthal and American maestro Thomas Keller, it remains steadfastly French at heart. The most significant foodstuffs are explored at generous length: four pages on lobster, three on charlotte puddings, two on pears.

Anyone set on exploring the demanding peaks of haute cuisine should grab Alain Ducasse's Grand Livre de Cuisine (£159) – that's if they can hold the 1,080 huge pages. The practicality of this vast tome is debatable for most cooks, but if you want to cook the legendary ortolan, the (illegal) recipe is on page 527.

Maybe the book is better for ideas. I saw a copy behind the counter at Brawn, possibly London's hottest restaurant of the moment, where the peasant cuisine is worlds away from Alain Ducasse's three-star style.

Though Silver Spoon (£29.95) is regarded as the pre-eminent collection of Italian recipes, the recipes in its 1,263 pages are rather erratic. It includes tarte Tatin and aringe al pomelmo (kippers with grapefruit) but lacks bagna cauda. For a practical guide to Italy's unrivalled everyday cuisine – pasta, bread, risotto and, yes, bagna cauda – I'd go for The Italian Cookery Course by Katie Caldesi (£30).

Doing the same job internationally, Darina Allen's Ballymaloe Cookery Course (£30) runs from Greek bean soup to lemon curd. I once saw a chef buy 10 copies at the Ballymaloe Cookery School for his kitchen staff. Everyone even remotely interested in cooking needs a reliably comprehensive book that covers the basics from pancakes to marmalade.

I tend to reach for The Good Housekeeping Cookery Book (£30) or Jill Norman's New Penguin Cookery Book (£20). For cooking (and growing) fruit and vegetables, you can find no more encouraging or wise advice than in the two volumes of Nigel Slater's Tender (£30 each).

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies