The great gamble of locking up your cash

A new 10-year bond is paying a glittering 4 per cent, but can that rate justify such a long commitment by savers, asks Chiara Cavaglieri

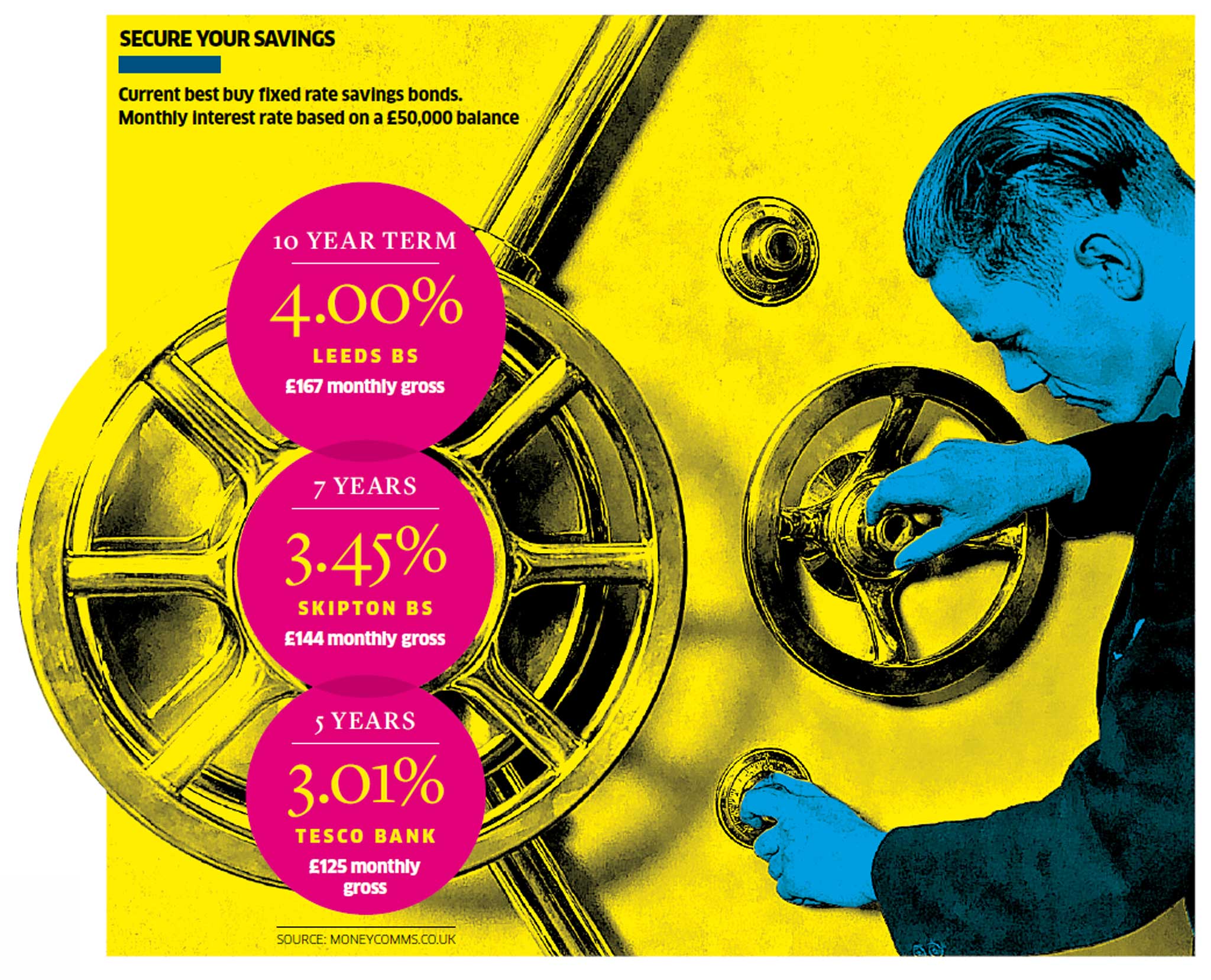

If you're on the hunt for any sign of life in the dead zone that is the current savings market, a new bond paying 4 per cent should offer some hope. Naturally, it comes with a sting in the tail – you have to lock your money away for 10 years – but with variable rates routinely paying a shameful 0.67 per cent, is it a gamble worth taking?

Leeds Building Society's brand-new, 10-year, fixed-rate bond pays eight times the Bank of England base rate, which was dropped down to a low of 0.5 per cent in 2009 and has been stuck there ever since. The last time there was a savings account paying 4 per cent was September 2012 and that was a five-year, fixed-rate bond from Halifax.

For a saver with a pot of £50,000, the monthly income – which is paid into a separate account – Leeds BS would be paying £166.66 (£133.33 after basic tax). The top-paying five-year deal from Tesco Bank pays monthly interest at 3.01 per cent, which equates to £125.41 per month (£100.33 after basic tax).

If income now rather than later is the primary concern, the Leeds bond pays an extra £1,980 in the first five years. If you are approaching or in retirement and so looking for safety, stability and as much money as possible coming in now, this 10-year bond could be a punt worth taking.

Andrew Hagger of the personal finance site Moneycomms.co.uk says: "Understandably, many people feel that 10 years is too long not to have access to their capital, but for those with the sole intention of getting the best monthly income they can from their nest egg, the 4 per cent rate will look very tempting".

The banks and building societies offering attractive rates on the longest bonds are taking calculated gambles that base rate will rise before they come to an end, which will mean they make extra profit. If they get it wrong and rates stay low, however, it is the long-suffering savers who will come out on top. Even when rates do rise, we can reasonably expect it to be a relatively slow process and it seems just as likely that many providers will take their time to pass on the increases to savers.

Mr Hagger points to the 10-year fixed-rate savings bond from Birmingham Midshires, which was launched in the summer of 2008 and, at the time, was thought to be too much of a risk by many people.

"In hindsight the rate of 6 per cent on offer at the time would have turned out to have been a very shrewd move," he says.

Only time will tell whether such a long fix at this rate represents great value, but even the experts and economists don't know with any certainty when rates will rise and this has made long-term fixes tricky to assess.

Ultimately, the decision must come down to your specific needs, but even if you don't need the income now, 10 years is a long stretch. There have been predictions that the first movement in base rate might come as early as summer 2015. If that is the case and rates start creeping up beyond 4 per cent, you could be stuck with an uncompetitive deal for another eight years.

Danny Cox, head of financial planning at Hargreaves Lansdown warns that 10 years is a long time to tie up your savings in cash when life has a habit of throwing curve balls at you, particularly if inflation is eating away at the value of any savings you do manage to grow over that time.

Mr Cox explains that if inflation were to rise above 3.2 per cent for a basic-rate taxpayer, or 2.4 per cent for a higher-rate payer, the 4 per cent on offer from Leeds BS would not be able to keep pace with rising prices.

"The rate on this bond is nowhere near good enough. The probability is that interest rates will rise long before the 10-year term is up and 4 per cent will look even worse value in the future than it does now," he says. "With equity-income funds paying dividends alone of nearly 4 per cent, with the potential for capital growth as well, this is where my longer-term savings are going."

If you are determined to keep your savings in cash, by far the biggest problem is finding a suitable alternative. At present, the average no-notice account pays an embarrassingly low 0.67 per cent, according to Moneyfacts.co.uk. In Isa (individual savings account) territory, the average variable account pays just 1.36 per cent, which only climbs to 1.94 per cent for fixed-rate Isas. Even if you bag the best-buy Isa from Virgin Money (Issue 70), you still earn only 3 per cent, fixed for five years until 2018.

Many current accounts are actually offering better value for savers at the moment. For example, the FlexDirect current account from Nationwide BS pays 5 per cent gross on balances up to £2,500 for the first 12 months (falling to 1 per cent thereafter). Clydesdale and Yorkshire banks pay 4 per cent on balances up to £3,000, although this drops to 2 per cent in March 2015, while the Santander 123 current account, which carries a monthly fee of £2, pays up to 3 per cent on balances of £3,000 to £20,000, 1 per cent on £1,000-£1,999 and 2 per cent on £2,000-£2,999. With all of these, you must either maintain a minimum credit balance to get the interest, or pay in a minimum amount each month.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments