From the myth of the Minotaur to the Hobbit and Dr No, where do stories come from – and who owns them?

The notion of 'the author' is a recent invention – and perhaps already on the brink of extinction. Andy Martin says there are three phases in the career of authorship: mythic, divine, and secular

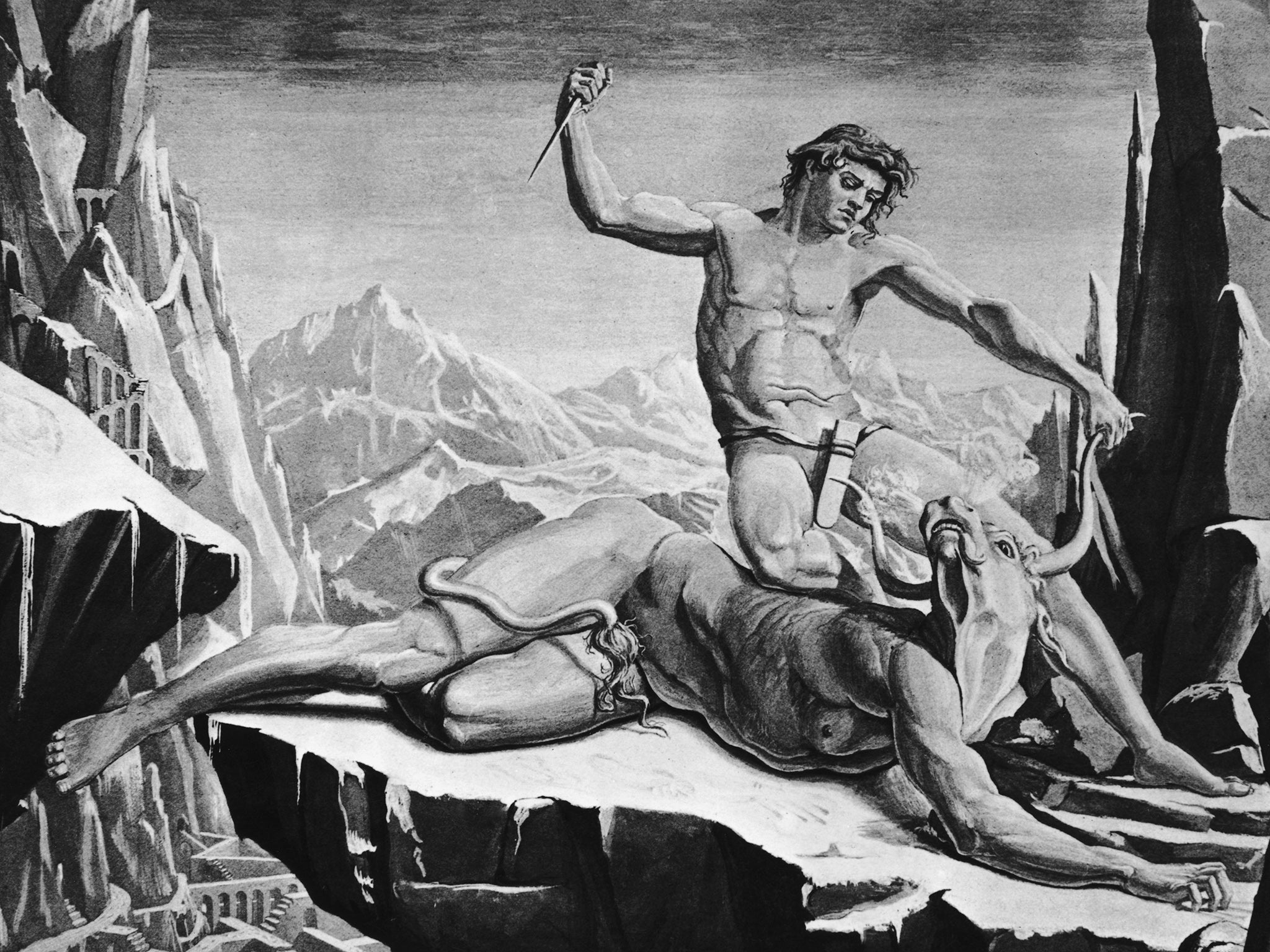

Harry tightened his grasp around his sword and ventured down into the deep dark dismal den of the monster. He was terrified, but courageous, and when he heard the terrible roar of the creature, he kept on going towards the sound. He didn’t have to go much further because this huge bloodthirsty killer, smelling his approach, came rushing right at him and would have added him to his long tally of victims, except that Harry was able to slice off his head with a single swish of his razor-sharp blade.

The beast was dead. The only problem for Harry was that he was now trapped underground with seemingly no exit. He was doomed. And no doubt he would have died if not for the benevolence of a beautiful woman, who came and led him up and out, back into the light.

I was about to write, “THE END”. Except that it never does end. Because I stole the story from who(m)ever, several thousand years ago, came up with the myth of the Minotaur in the Labyrinth who must be despatched by the cunning hero Theseus, who in turn is saved by Ariadne’s thread guiding him out again. I imagine that the basic narrative structure has been recycled a thousand times, the mainstay of many an epic tale. (You can find a much better version than mine in Plutarch’s Lives or Robert Graves’ The Greek Myths). Perhaps the grand tradition of the knight errant starts here. Robin Hood was a successor to Theseus. Echoes reach all the way down to Dr No and The Hobbit. And yet no one ever got sued for plagiarism. Why not?

Because the story of the Minotaur chomping up victims in his labyrinth had no author. Feel free to run with it. No letters from lawyers representing the Theseus Estate will drop on to your mat. Friends of the Minotaur will not be trolling you. It’s open access. The fact is that the very idea of “the author” is a recent invention. And perhaps already on the brink of extinction. I think there are three clear phases in the career of authorship: mythic, divine, and secular.

Did Homer exist? Almost certainly not. Or rather there were many Homers, over aeons, each adding something to the serial adventures of Odysseus and Achilles. Translators of the Odyssey do not have to pay the descendants of Homer for the rights. Even the more authorial Roman authors, say Virgil, picking up the story of what happened after Troy in the Aeneid, still gave credit to the gods for their inspiration. Or the Muses. Even if humans had to do the hard yards of actual writing.

The idea of “inspiration” (from inspirare) is theological in origin: it assumes that a deity or deities are on hand to “breathe” into the ear or the heart or the soul of the writer the story that they want them to tell. The narrative must transcend the merely human. Hence the idea of prophecy, broadly understood. Not mere prediction, but rather messages relayed from the great beyond.

In the beginning was the logos (so says Saint John). The words of the holy books, even though mediated through humans, are invariably transmitted from higher powers. Moses and Saint Paul are all divinely inspired. Muhammad had the Quran dictated to him by the Archangel Gabriel. But in each case there is a collective at work. Perhaps the brilliant English translator of the Bible, William Tyndale, had to be strangled and burnt at the stake because he appeared to be claiming some kind of individual authorship and thereby rebelling against the divine origin (and the Catholic Church). The committee responsible for the King James Bible was careful to keep well out of the limelight. No tweeting from them about the next big one on Kindle.

The idea of divine inspiration is not as crazy as it might (from our secular point of view) seem at first sight. Because, when you stop to think about it, where do these stories come from in the first place? What is the genesis of Genesis, for example? German historiography of the 19th century demonstrated the multiplicity of hands at work on it. And it took someone of the perversity and genius of Harold Bloom to write The Book of J, in which he zeroes in (in a strictly conjectural way) on the individual woman who wrote what he thinks of as the best parts of the text.

But even she, I imagine, would not have claimed that the figure of “Yahweh”, the story of the Garden of Eden, the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, was her personal invention. She didn’t make it up. Nobody made anything up. There were no fictions, no possibility of falsehood. Everything was true, because the author was none other than the Author of all things, the great Creator and Almighty One, if she/he/they were indeed One. The Flood was real. The Plague was real. Abraham really took his son up the mountain and was poised to sacrifice him, and so on. Real and, of course, allegorical all at once (“figura” as the great critic Eric Auerbach used to say).

God, in this sense, is simply a reflection of the collective, or the community. The divine and the human were in perpetual communication one with the other. Hence Jesus, hence Muhammad. Prophets were commonplace, everybody potentially had a hotline to God. And the stories descended like manna from heaven. Like grace. What the Argentine writer Borges has called “the spirit of literature” ie everything is teamwork.

And here we have the problem, fast-forwarding to the secular phase of the creative process: we tend to think in monotheistic terms. The creator of the mini-universe that is a book or a poem or a film is effectively singular. This is the assumption of “auteur theory”: a Hitchcock film, for example, is nothing other than the creation of one man.

It is clearly a mistake, but one that we were bound to make, ever since Dante included a figure called “Dante” in the Divine Comedy and has him led down into the Inferno by Virgil and up into Paradiso by Beatrice. Ever since Montaigne, in his Essais, suggested that their real subject was none other than himself. The collective is concertina’d into selfhood. The notion of an individual author is born. The genesis of the modern secular period lies in that opening sentence of the Commedia: “I found myself in a dark wood” (mi retrovai).

All contemporary authors, no matter how hard-boiled, see themselves, like Wordsworth, “wandering lonely as a cloud”. To put it another way, they are (or aspire to be) a brand. They really hate it when someone else comes along and steals one of their creations. I had this experience recently when the BBC used one of my works and repackaged it as their own. A year or so ago, I sat behind the thriller writer Lee Child and looked over his shoulder while he wrote a novel, from beginning to end. In search of the moment of genesis, trying to catch inspiration on the wing. Weird but original.

I was once trapped in a crowded bus in Nicaragua, had my watch ripped off my wrist, a gaping hole gouged in my satchel, and I was lucky to get out of there with my trousers on. I sort of felt afterwards that maybe their need was greater than mine. I don’t feel quite so forgiving where the BBC are concerned. Do they really need to rip people off? The answer, it seems, is: yes they do.

Other writers have told me about similar experiences. Mark Billingham happened to be watching CSI New York on TV when a strange sense of déjà vu crept over him. It turned out that the entire episode duplicated the plot of his award-winning first novel, Sleepyhead. Dan O’Hara, a literature specialist at The New College of the Humanities, recalls how as a student he had a whole conference, a couple of speakers, and even some computers purloined by the BBC with never a credit or whisper of thanks.

“Everyone steals everything,” said Simon Toyne when I checked with him. Toyne is the author of (most recently) The Boy Who Saw and the presenter of CBS Reality series Written in Blood. He is both an author and a “creative” as they say in media circles. He has been mugged many a time. “It’s like you’re strolling down the street with this shiny new piece of intellectual property in your hand, and you’re feeling ridiculously pleased with yourself, and suddenly this gang swoops on you and rides off with your work. And the funny thing is they still want you to like it.”

As per CSI, the BBC is not alone in this attitude. But perhaps it is alone in being pious about it. “They are always fishing,” says Toyne, “and they are like industrial trawlers with mile-wide nets hoping to scoop up all the minnows.” The classic wheeze is they invite you in to “pitch an idea”, then there is a period of silence, and the next thing you know it’s on television or radio and they are saying, “Oh, we were already thinking about that, you know.”

Toyne says that this was “one of the things that made him feel that he didn’t want to work in television any more”. He became a full-time writer because he wanted ownership. “When you write a book it’s like it’s one of your own children. When you see it kidnapped and sold into slavery you feel violated.” There is no (or very little) protection afforded to writers. “The plagiarists and the thieves know they can get away with it.”

The BBC it has some kind of divine right to pinch anything and everything and re-label. In the age of the infosphere, the notion of authorship is liable to be lost, hoovered up into a hazy sense of the great beyond, the undifferentiated logos, manna raining down, endlessly, effortlessly, unmediated by human hand. But the fact is that it is mediated. To be fair to the BBC, one of its producers – unsolicited – having seen the BBC's version of my work on the website wrote to me to say how ashamed he was of the righteous pillage and plunder attitude.

EO Wilson’s work in sociobiology – and most recently in The Origins of Creativity – tends to play down the individual in favour of the collective. The source of stories is not the tormented individual soul of the “flâneur” (as Baudelaire would have it) but a complex network of associations and inheritances and mutuality, well beyond any mere solo writer, all doused with “the emotions of our ancient primate ancestors”.

I would go further and say that the true origin of stories is lost in space. In his brilliant short story, “Jokester”, Isaac Asimov suggests that aliens conducting a psychological experiment are the true source of all jokes and our sense of humour. And what happens when we find this out? Our sense of humour will be no more. Ridiculous of course. But in the closing lines of the story, nobody laughs.

Our extraterrestrial past is present in all our narratives, even – or especially – when it is absent. Where did I come from? What am I doing here? These are the aching cosmic questions that dog even the most parochial and terrestrial of human narratives. God is an alien, obviously. But we too are aliens, strangers on our own planet. We are wandering particles of stardust still yearning after our common genesis in the Big Bang.

And if Teilhard de Chardin is right everything that we have lost in our billions of years of existence will be recovered and rolled up once more in the Omega Point, which will last for eternity. Therefore we occupy an intermediate twilight zone, betwixt origin and extinction. Dreaming of singularity, somewhere on a line between one and zero. But reports of ''the death of the author'' are greatly exaggerated. For the time being, until we all dissolve into the vast collective unconscious, we need to cling on to the idea of authors and not see them flattened out and rolled over by the wheels of a vast anonymous corporation.

Andy Martin is the author of Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me. He teaches at the University of Cambridge

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies