John Murphy: Businessman whose name was synonymous with the construction industry

From the outbreak of the Second World War right through to preparations for the London Olympics, John James Murphy organised armies of construction workers, many of them from his native Ireland, to provide a large slice of Britain’s infrastructure. His life took him from County Kerry’s Cahirciveen, one of Ireland’s most beautiful regions, to the mud of the building sites of London and elsewhere. In the process his name became synonymous with the construction business.

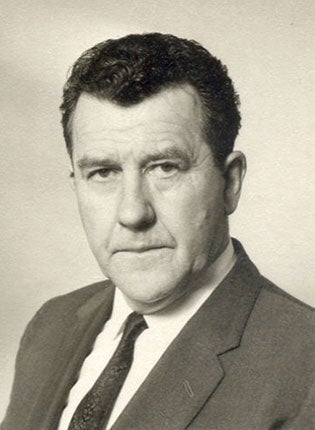

In his case the old saying that where there’s muck there’s brass was amply borne out. He ranked around 300 in the Sunday Times rich list, with an estimated personal worth of £190 million. He sought fortune but not fame – he did not, for example, like to reveal his exact age, and avoided personal publicity to the extent of once boasting that no one had managed to get a picture of him.

Instead he concentrated relentlessly on hard work and on landing the next big job for his company, J. Murphy and Sons. Its vans were a much more familiar sight than the man, for his fleet was to be seen all over Britain.

Since his vehicles were green he was designated Green Murphy: his brother Joe, also in construction, had vans of a different colour and was thus known as Grey Murphy.

John James Murphy was born on 5 October 1913 in Ireland’s deep southwest at Loughmark, near Caherciveen – “in the early years of the last century”

is as precise as the information on his age gets – and attended the local school in Curickeens. He is remembered as ambitious and with a strong sense of adventure. But in the west of Ireland in the depressed 1930s opportunities were few and unemployment was high so that, along with many others, he emigrated to London.

There he worked with various construction companies before taking on sub-contract work himself. With the onset of war in 1939, there was an urgent need for the construction of airport runways for the RAF, and for repairing those which suffered bomb damage. Among the airports Murphy helped build were Dunmore and Weathersfield in Essex and Sudbury in Suffolk.

In the early days of trading he oversaw multiple contracts himself while tendering for new work and developing his fledgling company. He did well in the period of regeneration and reconstruction in the 1950s and ’60s, diversifying into almost all aspects of construction. His approach was to expand within the building industry but not to stray into other less familiar areas.

In the 1950s he went into cabling and electrification, in the 1960s into roads, water service and Post Office cable installation, and in the 1970s into work connected with the introduction of natural gas. The 1980s saw him involved in major commercial developments in the City of London and in projects such as the Stansted Airport Rail Link. In the 1990s the Green Murphy vans were busy at the London Water Ring Main and Channel Tunnel Rail Link.

Today the firm is installing electric cables for London’s Olympic Park.

Such continuing success clearly indicates that Murphy, with little formal education, exercised immense shrewdness in keeping his firm at the forefront of the building and civil engineering industry for more than half a century. That industry changed hugely over the decades, but he showed an ability to adapt and modernise.

There were, however, legal troubles in the mid-1970s when a major official push against tax evasion resulted in criminal charges, though not against Murphy himself. After a prolonged legal battle, his company was fined £750,000, while two directors and the company secretary were jailed for three years. Other employees received suspended sentences and fines.

The judge in the case said: “I find it difficult to speak with moderation when a large, well-known, highly efficient and hitherto respectable company engages in a gigantic swindle of this kind.” The episode was a blow, but had no lasting effects on the firm’s success.

Although the company has workers from many countries it has always been known for employing Irishmen, especially from Cork and Kerry, and its headquarters has always been in or near the Kentish Town area of north London, traditionally an Irish area.

Many newly-arrived Irish knew what they could “get a start” with Murphy in the building trade. It was said of him: “He was of the view, and still is, that Irish people are most adaptable and diligent workers.”

He favoured people from the old country and in particular his relatives, many of whom worked for him. One namesake, Eamonn Murphy, has just retired, the company said with pride, “after 48 years of unbroken service.”

Until quite recently it was Murphy’s habit to drop in at some of his building sites, chatting with the workers. Construction industry lore has it that he would often step into a trench himself to instruct younger men on the correct way of wielding a shovel. His daughter Caroline was recently appointed vicechairman of the company.

His charity work and other activities recently brought him the Kerry Person of the Year award. He also supported medical research, specialist charities, education, and recreational and sporting activities in both Britain and Ireland.

At University College, Cork, he funded a civil engineering laboratory and a postgraduate research fellowship.

He maintained a long relationship with the college, employing many of its civil engineering graduates: one of them, who came to him as a graduate, worked for him for almost 50 years.

David McKittrick

John James Murphy, businessman: born Loughmark, Ireland 5 October 1913; married twice (two sons, one daughter, and one son deceased); died 7 May 2009.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies