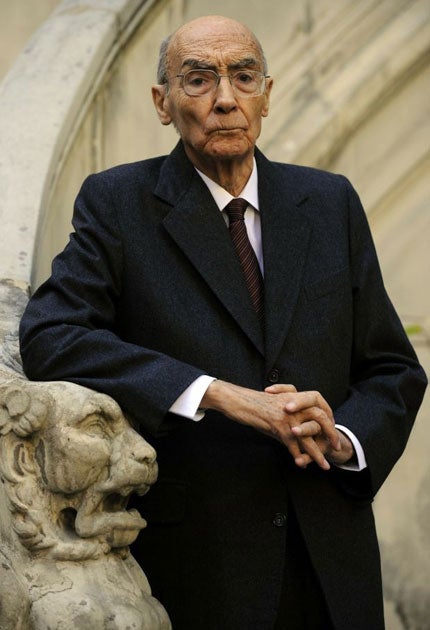

Jose Saramago: Nobel laureate who blended social realism with magical realism

In 1998, when Jose Saramago became the first Portuguese writer to win the Nobel Prize for literature, he was almost 76 years old, but his career as a novelist had not begun until he was 55. Saramago was honoured for work that blended elements of traditional European social realism with the magic realism of Latin Americans like Gabriel Garcia Marquez or Mario Vargas Llosa, in a style both baroque in its rich flow and modern in eschewing normal punctuation, with echoes of modernists like Jorge Luis Borges and Julio Cortazar.

His best known work in this country, Blindness (published as Essay On Blindness in Portugal) was also made into a successful 2008 film by the Brazilian director Fernando Meirelles. The sometimes surreal fantasies of magic realism provided him a way of approaching Portugal's troubled modern history; Antonio Salazar's military coup in 1926 saw the country ruled for nearly 50 years by a dictatorship with kept it backward, rural, isolated and Catholic.

Saramago was a dedicated communist and passionate atheist and his blunt views often courted controversy; he left Portugal in 1992 after the government withdrew his entry for a European literary prize because his 1991 novel The Gospel According To Jesus Christ had been deemed blasphemous by the Catholic church. Yet though he lived in Spanish Lanzarote, he actually continued to maintain a pied a terre in Lisbon. His use of the wider platform afforded him as a Nobel winner attracted international criticism in 2002, when he compared Israel's treatment of the Palestinians to the Holocaust and suggested it was time for Jews to stop using the suffering of the Holocaust as a justification for their actions. In his eighties, Saramago began an often outspoken blog, which was collected and published in translation this year as The Notebook.

Saramago was born Jose de Sousa on 16 November 1922 in the rural village of Azinhaga. Saramago was a pejorative nickname given to his father, meaning "wild radish", and was added to his birth certificate either maliciously or through a misunderstanding. Saramago didn't discover this until he entered school in Lisbon aged seven, and presented his identity papers. When the discrepancy of names was discovered, Saramago's father changed his own name.

When he was two, he parents had moved to Lisbon, where his father joined the police force. His older brother Francisco died of penumonia soon after the move, while Jose was left with his maternal grandparents, illiterate peasants who raised pigs. Saramago wrote movingly of his grandfather Jeronimo's influence in Small Memories (2006), and in his admiration of the old man's closeness to nature one can see the roots of magical realism with would stay with the young Jose.

The young Saramago became a voracious reader, and attributed his desire to become a writer to encountering a book of poems by Ricardo Reis, ostensibly a Brazilian but in reality a pseudonym used by the great Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa. But at 13 Saramago's parents, unable to afford grammar school, switched him to a vocational course. He became a car mechanic and welder, but gradually worked his way into a literary career, including stints as a publisher's reader and translator from Spanish.

He married Ilda Reis, a civil servant, in 1944; their daughter Violante was born in 1947, the same year he published his first novel, Country Of Sin, a social- realist tale of noble peasants; it has never been translated, much to the novelist's self-confessed relief. He spent the next three decades as a journalist, partly as a literary reviewer and, after Salazar's death in 1970, as a political columnist.

In 1966 he resumed publishing, with a book of poetry, The Possible Poems; over the next decade he would publish two more collections and three books of essays. At the same time his father was rising to become police chief of Lisbon, he joined the Communist party,

In 1974, when the dictatorship was overthrown by a leftist revolution, Saramago became deputy editor of Diario del Noticias, presiding over the firing of 24 journalists whose political views were unacceptable to the communists. So when in 1975 the political winds changed and a social democratic government took power, Saramago was fired from the paper. He returned to fiction, publishing, in 1977, his second novel, A Manual Of Painting And Calligraphy, which reflected many of the modern literary influences he had absorbed in the 30 years since his first novel.

His breakthrough came in 1982 with Memorial To The Convent, which, translated into English in 1987 as Baltasar and Blimunda, also became his first international success. The title characters, a one-armed soldier and a clairvoyant women, attempt to escape the Inquisition in a flying machine designed by a priest and powered by human will. He followed that in 1986 with his biggest domestic success, The Year Of The Death Of Ricardo Reis, which also won The Independent Foreign Fiction award, in which the psuedonym returns to Lisbon for the funeral of Fernando Pessoa. Set in the mid-1930s, its portrayal of Portugal under Salazar, mixed with Pessoa's right-wing optimism for Europe's future made it a best-seller.

In The Stone Raft, also published in 1986, the Iberian peninsula detaches itself from Europe, and drifts into the North Atlantic, while in The History Of the Siege Of Lisbon (1989), perhaps his most Borgesian book, a proof-reader inserts a "not" into an historical text, thus changing history, the present, and the future. Ironically, the furore around The Gospel According To Jesus Christ, which included sex between Jesus and Mary Magdalene, was considered by some to have aided Saramago within the politics of the Nobel committee, which had been thought to be dithering between him and Brazil's Jorge Amado in the choice of finally awarding the prize to the Portuguese language. Certainly the Vatican's reaction was to condemn the Nobel judges as "ideologically slanted".

However, his Nobel award was more likely directly prompted by Blindness (1995), an allegory in which an unexplained epidemic of blindness causes chaos to descend on society, and forces its characters into a Lord Of The Flies-like battle to survive. It was almost universally acclaimed, although it was somewhat predictably attacked by the American Federation of the Blind for being offensive to the seeing-impaired.

Its sequel, Seeing (2004, in Portuguese, Essay On Lucidity) was less successful. But Blindness also marked a change toward a more allegorical, less ornate style, using themes familiar in world literature, as evidenced by the long story Tale Of The Unknown Island (1997), or the novels The Double (2003) or Death With Interruptions (2005).

Having divorced in 1970, in 1988 he married a Spanish journalist, Pilar Del Rio, who has also translated some of his work. He died from multiple organ failure, after a long illness; he had been struck with pneumonia in 2009 but was thought to have recovered. His novel Elephant's Journey will be published in English later this year; Cain, the story of the Old Testament seen through Abel's brother's eyes, published in Portuguese in 2009, will appear in translation in 2011.

Jose de Sousa (Jose Saramago), writer: born Azinhaga, Portugal 16 November 1922; married 1944 Ilda Reis (divorced 1970, died 1998; one daughter), 1998 Pilar de Río; Nobel Prize for Literature 1998; died Lanzarote, Spain 18 June 2010.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments