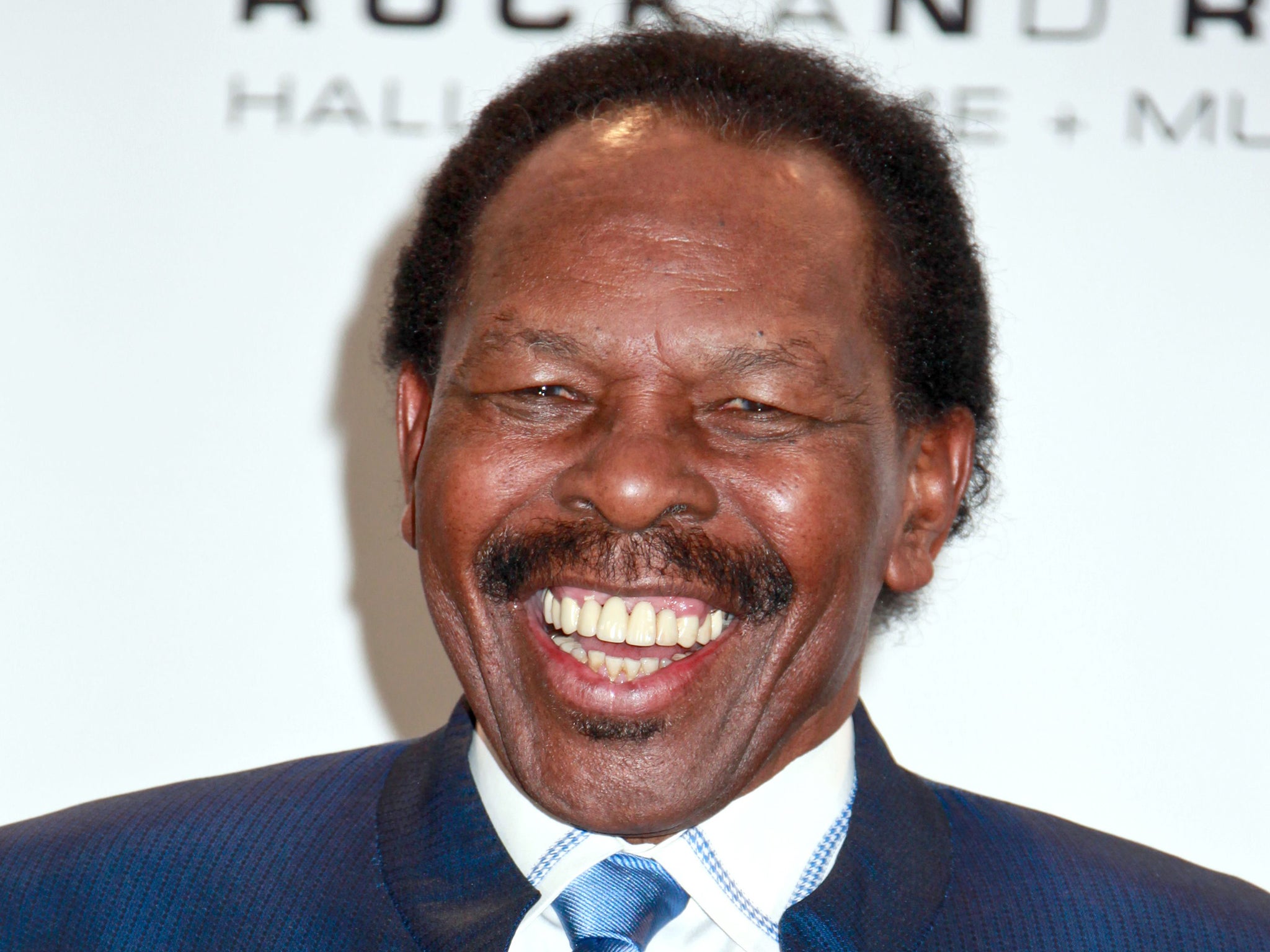

Lloyd Price: R&B pioneer and early rock’n’roll star

The musician, known as ‘Mr Personality’, penned hits such as ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’ and ‘Stagger Lee’

Lloyd Price, an R&B singer from New Orleans whose scorching 1950s recordings “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” and “Stagger Lee” became hits seminal to the development of rock music, and whose later endeavours included owning record labels and promoting boxing matches, has died aged 88.

Price gravitated to music in childhood, as he sought an escape from backbreaking work carting blocks of ice. He took up piano and later fronted a band in high school. At 19, he had an audition with Fats Domino’s arranger and music producer, Dave Bartholomew, who was floored by Price’s charisma – he was later dubbed “Mr Personality” – and the upbeat, yet plaintive, blues number he brought into the studio.

“Lawdy Miss Clawdy”, whose title came from an advertising catchphrase of a local DJ, Okey Dokey Smith, was released as a single in 1952. The song featured the distinctive piano trills and triplet rhythm of Domino on backup as Price wailed, “Lawdy, lawdy, lawdy, Miss Clawdy/ Girl, you sure look good to me.” It topped the R&B charts for seven weeks, attracted a huge white audience (Price was black) and over decades became a standard covered by dozens of performers, including Elvis Presley, Little Richard and – in their 1970 concert film Let It Be – The Beatles.

In 1954, at the peak of his success with “Lawdy Miss Clawdy”, Price saw his career interrupted by the draft. His music, he often said, was a threat to segregated society because both black and white kids were dancing to it.

“Truly, that’s one of the reasons why I got drafted in the service,” he told The New York Times decades later. “It was a revolution underground that nobody could stop. The lady at the draft board said Washington wanted me in the army. Their children were dancing to ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’.”

He returned to civilian life nearly two years later to find himself supplanted in popularity by Little Richard, the pompadoured singer whose career Price had helped boost after spotting him in a club.

At the beginning of his career, Price had the foresight to retain ownership of the copyrights and future royalties of his music. In 1956, he bought out his old record contract and went into business for himself, moving to Washington and launching the independent KRC record label his band director, Bill Boskent. He signed with ABC-Paramount in 1958.

He bobbed along in the R&B and pop charts of the late 1950s and early 1960s with songs such as “Where Were You On Our Wedding Day?”, “I’m Gonna Get Married,” “Lady Luck” and “Have You Ever Had the Blues” – brassy hits that paired his impassioned delivery with sunny big band and choral arrangements. “Personality” topped the R&B charts for weeks and was a No 2 pop hit.

His most notable success was “Stagger Lee” (1958), a punchy shuffle adapted from a black folk song that flew to No 1 on the R&B charts and reached No 1 on Billboard’s pop chart in February 1959. (The original ballad, alternately called “Stag-O-Lee” or “Stack-O-Lee”, had been recorded innumerable times since the 1920s. It recounted the 1895 shooting of St Louis gambler Billy Lyons by a pimp, Lee “Stack Lee” Shelton, in a fight over a Stetson hat and a dice game.)

In Price’s version, Stagger Lee “shot that poor boy so bad till the bullet came through Billy and it broke the bartender’s glass”.

Perhaps it was the manic enthusiasm – and a refrain that egged on a murderer (“Go Stagger Lee, go Stagger Lee”) – that moved television host Dick Clark to censor the ballad’s storyline for a rendition on American Bandstand. “Take out the shooting,” Price lamented to the Colorado Springs Independent in 2015. “Can you imagine that? Suppose he was playing records today!”

In 1962, Price started a record label with business manager Harold Logan. Double-L – named for the two partners – launched the career of singer Wilson Pickett. Price had one last pop hit for the label, an up-tempo version of the Erroll Garner ballad “Misty” in 1963.

Logan and Price then went into the nightclub business, with a midtown Manhattan venue they named the Turntable. The cabaret shut down after Logan was shot to death in the business office above the club in 1969. The homicide was never solved.

Price, who had known Muhammad Ali since the early 1960s, later moved to west Africa and helped boxing promoter Don King put together “The Rumble in the Jungle”, a 1974 heavyweight title bout in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), between Ali and George Foreman. Price was instrumental in staging a concurrent music festival that included James Brown and BB King, then helped King promote Ali’s “Thrilla in Manila” fight in the Philippines with Joe Frazier in 1975.

From his background as a performer, Price keenly understood the importance of showmanship. During the negotiations for the Ali-Foreman bout, he pushed King to do something that would symbolise his eccentric persona.

“He needed an image, a look, like Daddy Grace or Reverend Ike, who was his hero in those days,” Price told writer Jack Newfield in the King biography Only in America (1995). “I told him all stars have some unique gimmick that fans can recognise them by – a hat, a uniform, a way of dressing.

“As I was saying that, Don was absent-mindedly pulling on his hair, which was his habit when he was thinking. I stopped and said, ‘That’s it! That’s the look right there.’”

Lloyd Price, one of 11 siblings, was born in Kenner, a suburb of New Orleans, on 9 March 1933. His father was a labourer, and his mother owned a fried-fish stand where the future musician grew enthralled by jukebox records of jump-blues singers Louis Jordan and Amos Milburn.

Price was leading a band when Bartholomew, an influential New Orleans musician and talent scout, arranged for an audition with producer Art Rupe, owner of Specialty Records.

“At the audition, Lloyd was the only one who impressed me,” Rupe told writer Marc Myers in the rock-history book Anatomy of a Song. “Lloyd’s voice and the way he sold it had gospel’s intensity.”

“The first time I heard myself on the record was four weeks later,” Price told Myers. “I was helping my father and brother instal a septic tank in our backyard. The radio was playing and Okey Dokey announced my song. My brother looked up and said, ‘Hey, don’t you have a song like that?’ At the end, Okey announced my name. I felt like I was flying.”

After returning to the US in the 1980s, Price returned to performing, often with fellow veteran R&B singers such as Ben E King, Jerry Butler and Gene Chandler. He expanded his business interests to include housing construction in the Bronx, a limousine business and a prepared food company.

In 1998, when Price was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, he initially considered declining the honour.

“It was blatantly disrespectful that it took this long,” he told the Boston Herald. “But I understand why it took so long. Because of me being a rebel.

“There’s still resentment toward me,” he added, “because I controlled all my own songs … Shouldn’t the creators get a share of their creations? I think that’s right. And I believe you have to stand up for what you think is right.”

He is survived by his wife of more than 20 years, Jacqueline Battle; five children; a sister; and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Lloyd Price, musician, born 9 March 1933, died 3 May 2021

© The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.