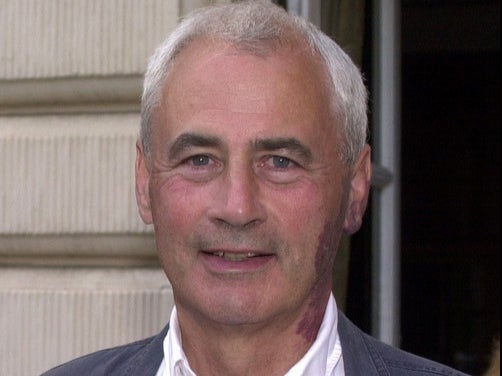

Oliver Gillie: First health editor of The Independent and devoted campaigner

A pioneer of the human style of reporting health and medicine, the writer was an important influence on modern health journalism

When The Independent launched in 1986, it carried one innovation that would soon be copied by all its rivals. The first edition, on Tuesday 7 October, carried a page entirely devoted to health stories, which was the responsibility of its health editor, Oliver Gillie, who has died, aged 83.

The idea for a health page had come from Andreas Whittam Smith, the paper’s founder, who hoped it would attract classified advertising. In that he was disappointed, but as an editorial concept the page was a great success. It presented science and medicine seen through a personal lens, an approach that has since become commonplace. At the time, however, some papers found it hard to grasp. The Guardian soon launched its own health page, which for months carried articles about health policy and the NHS before the penny dropped. “They were only interested in people as numbers,” Gillie later wryly observed.

There was a view among senior editors in the Seventies and Eighties that human stories were not serious. Health was seen as a woman’s subject, of minor importance beside the major issues of politics and world events. What became clear was that health was not of minor interest to readers. It drove circulation and as the realisation dawned, health coverage expanded. By the mid-1990s, The Independent had four specialist reporters covering science and health.

Gillie was a pioneer of the human style of reporting health and medicine and an important influence on modern health journalism, tackling subjects from acupuncture to impotence well before they became mainstream subjects of discussion. Although he had a popular approach, he was no lightweight. He started his career as a research scientist, obtaining a PhD in microbial genetics before joining The Sunday Times under editor Harold Evans, who was interested in what Gillie called “body maintenance”. A series of award-winning articles followed, and many books, including one of the first detailed reports of a heart transplant, seen from the operating theatre.

Later in his career, after leaving full-time journalism, he returned to his science research roots, becoming interested in Vitamin D and subsequently campaigning for the government and organisations such as Cancer Research UK to introduce a “rational, evidenced-based public health policy” on the vitamin which he argued most Britons were lacking because of advice to avoid the sun.

Oliver John Gillie was born in North Shields in 1937 to John Calder Gillie, a nautical instrument maker and Quaker elder, and Ann Gillie (nee Philipson), a distinguished regional artist. He was one of four brothers (one adopted) and was educated at Bootham School, York and Edinburgh University and was a Fulbright scholar at Stanford University, US.

He worked under Sir Peter Medawar at the National Institute for Medical Research in London and published five papers in peer-reviewed journals before a falling out with a colleague prompted him to start writing articles for the press. At The Sunday Times one of his most celebrated pieces was a 1976 expose of the noted psychologist Cyril Burt, who was found to have recycled or fabricated some of the data in his famous twin studies purporting to show the heritability of intelligence as measured in IQ tests. The episode became known as the Burt Affair and remains controversial to this day.

As a reporter, Gillie had a laid back, unhurried air which disarmed his interviewees. But he was also tenacious and, by his own admission, a bit of a zealot. He was born with a large strawberry birthmark covering his neck and left cheek which caused him embarrassment as a young man, none more so than when interviewed for a place at Cambridge University by a man with an even larger birthmark. The interview did not go well. He later wrote about living with a birthmark and presented a documentary on facial disfigurement.

Helped by his good looks and natural resilience he considered but rejected plastic surgery because “I felt I would not be myself”. It may be fanciful to suspect any connection but there is a neat symmetry with his later campaign against Cancer Research UK’s instruction to “always cover up” in the sun, which he pursued with extraordinary energy for more than a decade.

His fascination with sunlight and its role in supplying the body with vitamin D – essential for healthy bones and, he believed, to prevent many other diseases from multiple sclerosis to cancer – developed in the late 1990s. He devoted all his time to researching, lobbying and campaigning, setting up a private, non-profit Health Research Forum which published “Sunlight Robbery” in 2004. He could sometimes be seen walking the streets of north London topless, insisting it was “OK to take your shirt off” – to the consternation of his family.

Cancer Research UK subsequently modified its advice from “always cover up” to “spend some time in the shade” to protect against skin cancer. The government also shifted position and now recommends vitamin D supplements for young children and older people in a change from earlier advice. Six copies of “Sunlight Robbery” were requested by policymakers in Australia where senior scientists told me it had influenced their thinking, as I reported in The Independent in 2006.

A later paper on “Scotland’s Health Deficit” was published in 2008, in which he argued people’s poorer health north of the border was due at least in part to its cloudy skies. It was widely covered in Scotland, received plaudits from other scientists and led to a meeting with Sir Harry Burns, Scotland’s chief medical officer. In 2014, the Medical Journalists Association conferred its Lifetime Achievement Award on him for his work raising awareness of vitamin D.

Oliver Gillie is survived by Jan Thompson, managing editor of The Guardian, and their sons Calder and Sholto, and his daughters Lucy and Juliet from his marriage to filmmaker Louise Panton.

Oliver Gillie, journalist, scientist and campaigner, born 31 October 1937, died 15 May 2021

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies