Alan Johnson, Ian Hislop and Tamsin Greig on the ideas of the great 19th-century social reformer Octavia Hill

Five champions of Octavia Hill reveal why her goal of 'nobility for all' still matters

Ian Hislop

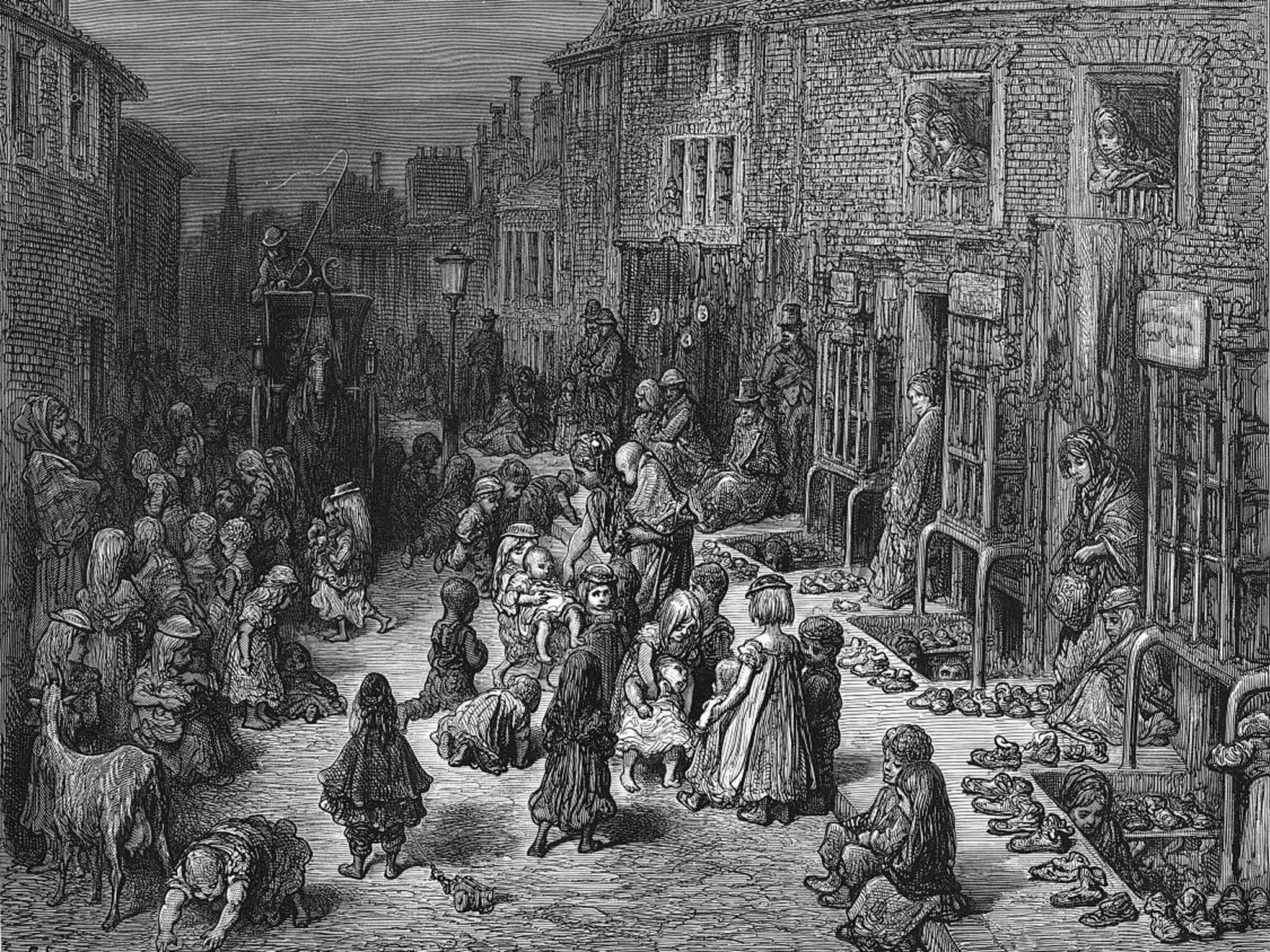

A few years ago I made a documentary called Age of the Do-Gooders to reclaim that pejorative term and reappraise the reputations of some of the great reformers of the Victorian age. Octavia Hill was one of those I profiled and, like many of them, she was both brilliant and brittle, inspiring and infuriating, dogmatic and yet an undeniable force for good. I focused, in particular, on her compassionate yet hard-headed approach to social housing, where she demonstrated a characteristic mixture of idealism and pragmatism. Anyone insisting on “order, cleanliness and self-respect” from those who had lived in London's worst slums was aiming high – but it worked.

I interviewed a long-term resident of a property owned by Octavia, the descendant of Hill's own organisation, and he told me about the “strict but fair” ladies who inspected the properties and tried to make sure that social housing (and its occupants) remained > “decent”. He called them “disciples of Octavia Hill” and talked enthusi- astically of 'high standards', Housing was, however, just one area in which Hill made a contribution to national life but the remarkable thing about her was not just her breadth of interest but the depth of it.

Her aims were certainly “noble” yet they were firmly rooted in reality. Like many others, she had read about London's poor but then she went and acted on first-hand experience. Victorian women often became involved in charity largely because they were excluded from traditional professions and routes to influence, and charitable work enabled them to make a genuine difference to society. It was respectable for middle-class women to worry about poverty, particularly in the domestic sphere, and Hill turned this to her advantage in realising that her initiatives in the field of what we would now call “welfare” had an effect on other spheres of life. She worked hard and, despite repeatedly suffering from exhaustion, she bestowed a huge legacy. When I think of her I always recall the figure described by George Eliot at the end of Middlemarch who may not be a great heroine but who works in unseen channels for the greater good of all.

But the effect on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

I hope Octavia Hill is not forgotten and that she remains a source of inspiration. She was, of course, deeply religious and this motivated her in her desire to “make individual lives noble”. Even though we are uneasy nowadays with her religious views and uneasy even with the word “noble”, if you substitute “noble” with “dignified” and talk of “giving people their dignity” I think it is pretty clear that her vision is as relevant now as ever.

Ian Hislop is a writer, journalist and broadcaster. He has been editor of 'Private Eye'since 1986 and is a team captain on the BBC show 'Have I Got News for You'

Tamsin Greig

I am sitting in the Red Cross Garden in south east London, originally laid out by Octavia Hill in 1887 as part of her vision to encourage people to live “noble lives”. The park has been recently restored to its original Victorian design, an oasis of wild flowers, meandering paths and a tranquil pond overlooked by six pretty cottages. This oasis reminds me of a garden lovingly raised by my friend and neighbour, Albert Rawlinson, on the land that backs onto the railway line in Kensal Green.

Albert died this year. He was 100 years old, more than twice my age. I met him in 1996, already in his eighties then, but still active and energetic. I went with him and his wife Lilian every Thursday to do their shopping. They did everything together.

On my wedding day, as we were walking back up the aisle, Albert leaned over to me and whispered: “Don't worry Tam, the first 60 years are the worst!” He was always playful and kind-hearted. The twinkle never left his eye, even in his last days when he was bed-bound and mute.

Albert worked on the railways all his life, starting at age 14. He married Lilian before the Second World War and they raised three sons in a one-bedroom flat overlooking the railway lines. Albert was the eldest of eight, served in the army during the war, helped build the local scout hut, was a churchwarden and became Head Ticket Inspector at Euston Station. He was loyal, practical, good-tempered – and was part of the community that welcomed and integrated with the influx of Caribbean families who moved into the area during the Fifties.

But he never liked to talk about himself, and he never complained. Not even when they lost two sons to cancer, not even when they lost a grandson at too young an age. Not even when Albert lost his beloved wife to dementia.

My friend ended his days living in a lovely assisted-living apartment in a north London care home. In June 2014 they organised a celebration in the home to mark the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landings. Albert was the guest of honour. I arrived at the party to find him sitting in his wheelchair wearing a row of medals. He'd never thought to mention that he had been one of the Allied soldiers to land on the Normandy beaches. When I asked him why he'd never told me, he just shrugged. “What was it like?” I pushed. After a short pause he said quietly: “Terrible.”

It was only at his funeral that I learned that Albert had helped many of the injured victims after an IRA bomb exploded in Euston Station in 1973. Another act of heroism that my friend kept to himself.

Albert was an ordinary railwayman who showed extraordinary bravery through a century of extreme change. He loved his garden oasis beside the railway lines, he loved the teamwork of a 77-year marriage and he loved his ever-widening family. He lived an undocumented but deeply noble life, and the forget-me-nots he gave me from his garden to plant in mine remind me daily that a more noble life is ours to be embraced still.

Tamsin Greig is an actress who has starred in 'Black Books', 'Green Wing', 'Friday Night Dinner' and 'Episodes', and has recently appeared in the West End in 'Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown'

John Bird

The Victorian era produced some great people – far greater, in my opinion, than those produced today – including, for example, the indomitable traveller Isobel Bird (no relation); John Ruskin, the one-man army who sought to bestow a renaissance roundedness upon everyone, whatever their class; and the dogged and passionate Octavia Hill – social campaigner, housing reformer and nature champion.

I discovered Octavia while researching social responses to housing and homelessness. I rediscovered her when I looked into the creation of the National Trust and the late Victorian campaigns around the social justice issue of protecting nature so that all of us, irrespective of our social standing, could enjoy its inspiration.

When I started The Big Issue I did it using Octavia as a model. She understood that social justice was as much about the bricks and mortar around you as the education you received and the work that you carried out. She bought land and built houses and began to raise the issue of reform through practical applications of housing justice.

At that time, most housing stock available to the hardworking poor was substandard, unhealthy and expensive. So why did Octavia invest in housing for working people and build superior stock when she could have made a fortune stuffing the people into slums? She did so because she was ahead of her time; because she was both entrepreneurial and socially responsible.

It is hard to believe that, back in the 1880s, Marylebone had many slums. Octavia moved in and built superior housing for hardworking poor people; and she did it as a business. She made it wash its own face in the same way that, many decades later, I started The Big Issue and have made it self-sufficient ever since.

Over a decade ago I looked out of the window of my Marylebone flat and saw a blue plaque commemorating Octavia. At that time I lived in a block that backed onto Octavia's first experiments in the business of social housing. I felt incredibly privileged that I was so close to her social experiment, to her entrepreneurial social endeavour.

I am not a historian but I am a passionate believer in a world that people like Octavia Hill fought for: a world where all of us have the opportunity to share nature and society; where all of us – whether we use a hammer or a pen – can feel included. I only wish she was around for us today, for housing and social inclusion is, once more, at a premium.

Octavia cannot and will not be forgotten, so long as there is someone whose life is narrowed by the housing in which they live. As long as there is injustice in housing, the spirit of Octavia will remind us that it could – and should – be done better and that we need not accept less for those who deserve more.

John Bird is the founder of 'The Big Issue', the world's most successful street magazine. Born into poverty and raised in social care, he was a prison inmate, artist and poet before becoming a political activist and author

Alan Johnson

As a child in early 1950s North Kensington I was unaware of the enormous political and social challenges facing post-war Britain. I certainly didn't regard the houses we lived in as slums, or feel that we were particularly unfortunate, but the houses on our street were very different to the ones my mother cleaned for a living in South Kensington. During school holidays she'd take my sister and me with her to work. The houses she cleaned were grand and, understandably, many of the occupants were irritated at the prospect of a pair of ragamuffins playing in their elegant drawing rooms. If we were allowed in, we'd watch my mother on a chair stretching high to dust or kneeling to scrub, scrape and polish.

Linda and I didn't expect to live in such houses. Their occupants were from a different world connected only peripherally to ours. The people whose houses my mother cleaned owned their homes while everybody in Southam Street, London W10 rented, so far as we knew. The families who shared our front door would come and go, just as we came and went; from 107 to 149 Southam Street and from there to 6 Walmer Road. Some of our neighbours rented from what I later heard described as slum landlords, the most notorious of whom was Peter Rachman, but we were with the Rowe (later Octavia) Housing Trust, something my mother told us we should be eternally thankful for. Her dream was to live in a house with her own front door; a release from our shared accommodation with no bathroom, no running hot water and a dilapidated outside toilet.

While we waited for my mother's dream to be fulfilled, the Trust met our needs, moving us from one room to three and then, even after my father had left us, to four rooms. My mother even persuaded them to install a bath and copper boiler in one corner of the decrepit basement with brown formica boards around it – our first bathroom.

My mother may have neglected to tell the Trust that her husband had deserted her for fear of not getting a bigger dwelling – I don't know. What I do know is that while she acquired many debts she always paid the rent on time.

Rowe/Octavia had an office on Portobello Road (known to locals as The Lane). My mother would “go up The Lane” every week to hand the money to a clerk who would initial the rent book. I can still picture that office; cream woodwork, brown lino and a strong smell of disinfectant. Battered by ill fortune and dogged by poor health, my mother's basic human need for shelter had at least been met and she wasn't going to let that slip away. Rowe/Octavia was our source of security – a “trust” in more ways than one. We three were just a few of the many people over the years who have relied on its services and been thankful for its existence.

Alan Johnson is the Labour MP for Hull West and Hussle. He is a former Home Secretary and Shadow Chancellor

Maxine Peake

I had always been intrigued by the Octavia Hill properties near Waterloo and it was only by seeking out who she was about 10 years ago that I became aware of Octavia and her work. What I admire about her most is her vision and her work ethic. She was an enabler – she helped people to help themselves. She promoted the importance of self-improvement, education, the arts and the idea that, ultimately, people will give respect when they feel respected. Tantamount to this is a sense of community and belonging, and Octavia provided this by encouraging recreation and access to open spaces for the masses. Octavia was extremely driven, a visionary.

I think she'd be horrified by the conditions some people have to endure in modern society. I certainly am. We are in a dreadful state regarding social housing and welfare. One of the many terrible things that Margaret Thatcher did was to create the right to buy; it contributed to our shocking housing shortage and this issue hasn't been properly addressed by subsequent governments. And landlords up and down the country are allowed to charge ridiculously overpriced rents on properties that are not fit for purpose.

Many poor people are vilified by the media and by politicians, and this bullying, scapegoating behaviour has a knock-on effect where people feel that they have slipped off the social scale; that they have no future and no hope. It's criminal.

Unfortunately, I think Octavia would need to address the same issues today that she tackled during her lifetime. The rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer – we need a modern-day Octavia to get us back on track.

Maxine Peake is an actress. She has starred in 'Dinnerladies', 'Shameless', 'Silk', and 'The Theory of Everything'

These pieces are taken from 'A Life More Noble – reflections on Octavia Hill's ambition of nobility for all', published by Octavia on 21 October at £9.99

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies