Safeguards on Britain's mass spying programme 'clearly defective'

GCHQ bulk collects communications data from people 'of no intelligence interest at all'

Safeguards to stop the British Government’s mass surveillance programme wrongly spying on journalists and human rights groups are “clearly defective”, the European Court of Human Rights has heard.

The UK has been taken to court over its mass spying and surveillance operation, the true extent of which was first revealed in leaks by former CIA contractor Edward Snowden in 2013.

Groups including the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, the Open Rights Group and Big Brother Watch say that GCHQ’s TEMPORA interception programme not only breaches privacy rights but undermines important work done by investigative journalists and defenders of human rights, who need to communicate anonymously with sources.

The Government says putting extra safeguards on the programme would do “profound damage to the capabilities and work of the UK intelligence services”.

GCHQ, the spying agency which conducts the mass surveillance, “retain and store very large volumes of data relating to millions of people, even when those individuals are of no intelligence interest at all”, Dinah Rose QC, representing the applicants, told the court.

She said the Regulatory and Investigatory Powers Act, which governs the operation of the programme, was “complex and opaque” and that it featured “clearly defective” safeguards.

Key to the argument of the groups is the fact that the UK freely exchanges its mass surveillance data with the US, where the same legal protections are not in force. Ms Rose cited revelations from the Snowden leaks that appear to show that “even the minimal provisions of RIPA do not apply to this material”.

“The activities also breach the applicants’ rights to freedom of expression, including the vitally important right of journalists and human rights NGOs to impart and receive information in confidence,” she said – noting that these professions were not exempt from the snooping.

The groups also say that the Investigatory Powers Tribunal, which was set up to supervise the data collection “lacks independence from the agencies whose conduct it has been created to supervise, its procedures are flawed and unfair, and the remedies it can give are inadequate”.

The British Government neither confirms nor denies whether it retains communications content, such as phone calls, but has admitted it keeps communications data, such as numbers dialled, websites visited, and a list of people emailed.

Helen Mountfield QC, also representing the applicants, told the court that because of the international nature of the internet, often whether an email passed under the jurisdiction of British intelligence agencies was “a matter of chance” because it depended where any given server was located.

“The fact that domestic law offers such different protections to the same uses by the same security services of the same data, simply by virtue of the route it travels appears quite arbitrary. It certainly calls for a rational explanation, and none has been provided,” she said.

James Eadie QC, who was representing the British Government in the court, however, accused the applicants of having falsely conjured up “a spectre of vast privacy intrusion”.

“These applications raise issues of the utmost importance for the United Kingdom,” he said.

“If the applicants’ case on the legal requirements for interception and intelligence sharing in this context were to be accepted the result would be profound damage to the capabilities and work of the UK intelligence services.

“The nature of the safeguards against unwarranted intrusion, on the right to proper respect for privacy, need, we say, to take into account the impact on the ability of the Government to protect the lives and safety of the public, all the more so in light of the string of appalling atrocities across Europe.

“Whilst privacy rights are important and to be respected, the right to life is paramount. In this sphere, national security is not an end in itself. The intelligence services operate, as far as they can in a dangerous world, to protect the public.”

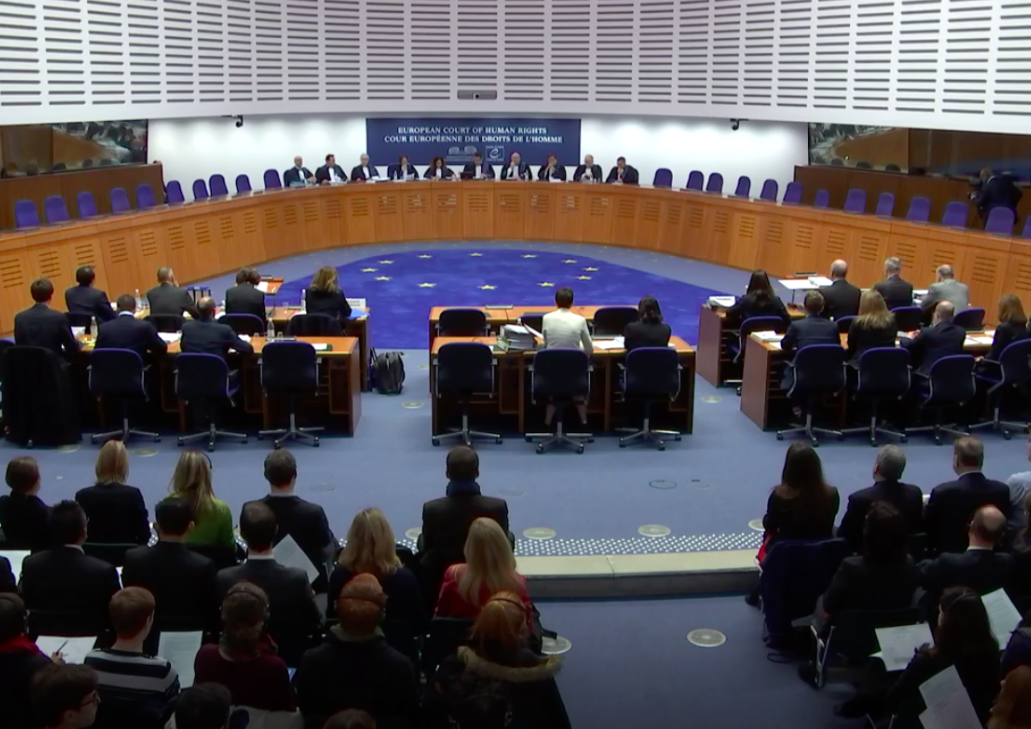

An application to the Strasbourg court on the issue was first made in 2013, with additional organisations making further complaints in 2014 an 2015, and was heard in the grand chamber on Tuesday.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies