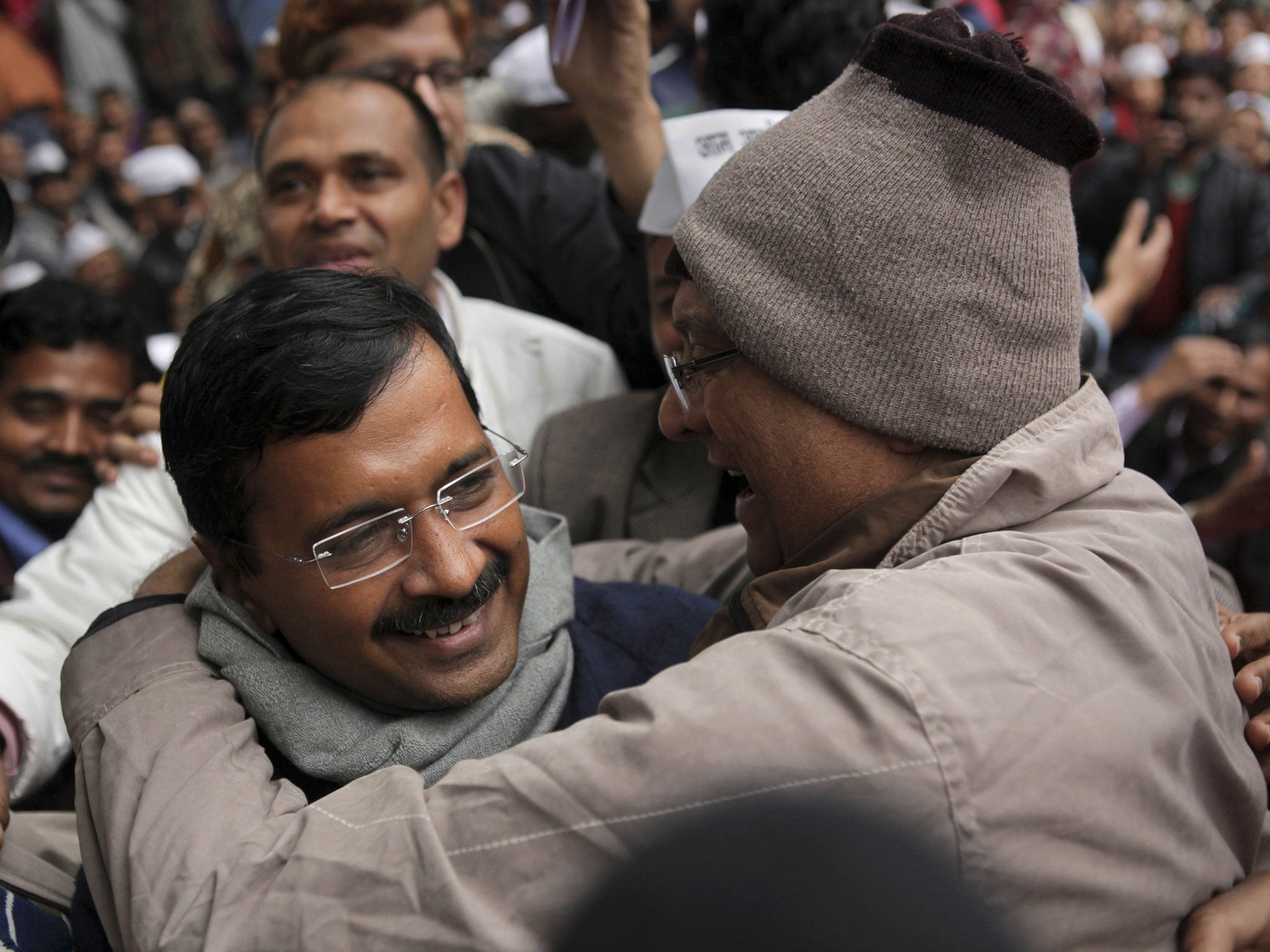

Arvind Kejriwal's 'Common Man' sweeps to power in Delhi and now he wants to save India from corruption

The leader of the new ‘Common Man’ party sweeps opposition aside in city election, promising transparency and to contest general elections. Andrew Buncombe reports from Delhi on what is being called a revolution in Indian politics

Arvind Kejriwal believes he is marching at the front of nothing less than a revolution.

Last week, the activist-turned politician was sworn in as chief minister of Delhi and promised the voters who propelled him and his Aam Aadmi (Common Man) party into the unexpected position, that he was there to serve.

“Today the common man has won,” he declared. “Till now we used to think that India cannot be saved from corruption but today the people of Delhi have shown that elections and politics can be done with honesty and integrity.”

The 45-year-old Mr Kejriwal and senior members of his one year-old party have got down to work with unprecedented speed. On his first day of taking office he announced the people of Delhi would receive free water and on his second he declared he was slashing electricity bills. He refused to allow a bad case of Delhi Belly – to which he confessed to having fallen foul of on social media with perhaps more detail than was required – to slow him down.

But alongside the flurry of activity, it was an announcement made by the Aam Aadmi party (AAP) in the aftermath of the Delhi election that has gripped debate in recent days. Having performed better than anyone expected in the polls, the AAP has said it will contest at least 300 out of 543 seats in the upcoming general election. If the success the party enjoyed in Delhi could be replicated elsewhere, people have asked, could the up-start party it be strong enough to have an impact at a national level?

“It is a revolution because the people of Delhi have made sure honest people have come forward and the corrupt have been side-lined,” said Rajesh Garg, an AAP politician who took his oath this week.

Unlike many members of the more established parties who arrived at the white-washed, British-built assembly building in Delhi to take the oath in chauffeur-driven SUVs, Mr Garg drove himself on a rickshaw given to him by supporters while wearing a white cap of the style favoured by Mahatma Gandhi. “There is nothing wrong with having a big car, but there is no point getting a big car by corrupt means,” he told the media.

Mr Kejriwal, a former tax official who has been an activist for the past 15 years, has steadily courted the support of the people of Delhi, tapping into growing anger over public corruption and a perceived failure on behalf of the Congress-led federal government to deliver. The anger witnessed in India echoes protests in Pakistan, Brazil, Turkey and elsewhere.

In 2011 he accompanied Gandhian activist Anna Hazare, who led huge demonstrations across the country in support of a national ombudsman. In 2012, when it was proposed that the campaigners should establish a political party, Mr Hazare declined to join.

Many assumed the party would fail without the totemic figure, but Mr Kejriwal campaigned assiduously, promoting a corruption-free agenda and taking aim at high-profile targets such as Robert Vadra, the son-in-law of Congress leader Sonia Gandhi, who was accused over land deals. (Mr Vadra denied the allegations.) The party’s symbol was a broom, something that resounded with many of its poorer supporters.

“I like the AAP. I voted for them,” said Raju Rajmal, a rickshaw driver, speaking on the day it was announced Mr Kejriwal was to become chief minister. “The [other parties] have many years to do things. This is the first time for the Aam Aadmi.”

Mr Kejriwal’s party came second in Delhi elections, but the first-placed Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which also failed to win a clear majority, was unable to secure sufficient support from other parties. The AAP is receiving “outside” support from the Congress.

Since having been thrust into office the party has been attracting widespread attention. Hundreds of thousands of rupees have been flowing into the party’s coffers from supporters while a series of high-profile names have joined the huge numbers of ordinary people signing up. Meera Sanyal, a former senior executive with the Royal Bank of Scotland in Mumbai, announced on Thursday that she had joined.

In recent days, large crowds of supporters have been gathering outside Mr Kejriwal’s house on the eastern fringe of Delhi. When The Independent visited, workmen with welding equipment were repairing the Girnar Apartments’ metal sign that had been knocked over by the crowds. (A spokesman for Mr Kejriwal said he was not well enough to give interviews.)

At the nearby party office, volunteers were taking the details of people coming to join. One man, Anjani Kumar Sharma, said he come all the way from the state of Jharkhand – a 22 hour journey by train – simply to join and in the hope of meeting Mr Kejriwal. “There is a lot of corruption in India,” said Mr Sharma, who has his own commerce coaching business. “Wherever you go, you will find corruption.”

Ahead of the Delhi state election, most analysts had been predicting that the BJP and its charismatic but controversial leader, Narendra Modi, were likely heading for power in national elections that have to be held by the spring. In recent months, Mr Modi, the chief minister of the western state of Gujarat has been touring the country, riding a wave of anti-incumbency anger against the ruling Congress party and enjoying large, enthusiastic crowds wherever he appears.

Yet Mr Modi’s victory is far from guaranteed. The BJP has previously found support from only a portion of Indian states and despite the apparent dissatisfaction with the Congress, the party would have to secure a wave in the so-called “Hindi heartland”, to see him home. If the AAP were able to secure just a modest number of seats, the BJP could be forced to rethink its arithmetic. What that might mean is uncertain.

Ajay Gudavarthy, a political scientist at Jawaharlal Nehru University, said the party could do well in places where corruption had become a particularly resonant political issue, such as the state of Karnataka.

“Where those issues, it could eat into the support [of the major parties] and in the metropolitan areas, it could even win seats,” he said. “Bangalore is a good example of this.”

Rahul Gandhi, son of Sonia, great-grandson of Jawaharlal Nehru and the man leading the Congress campaign, has said his party must take note of the AAP victory in Delhi. (The AAP has already said it will challenge Mr Gandhi in his Amethi constituency in the general election.)

The BJP, meanwhile, has dismissed the APP’s success. Prakash Javadekar, an MP and party spokesman, said people voted in different ways in different elections. He claimed the publicity surrounding the AAP would change within two weeks. “The BJP is the preferred party for parliament,” he said.

Some believe that regardless of the outcome of the general election, the AAP, with its policy of transparency over its funding and the background of its supporters - something that has previously been largely Indian politics - has already had a lasting impact.

“The most important thing about AAP is not how many seats it will capture in 2014, but how it will change the grammar of Indian politics,” said Sadanand Dhume, a fellow with the American Enterprise Institute in Washington. “In the age of 24X7 television and social media, the upstart new party has already put tremendous pressure on older players to rethink fundraising, candidate selection, campaigning and accessibility to the public.”

Meanwhile, Mr Kejriwal and his supporters are looking ahead.

“The things that Kejriwal is doing, the other parties only talk about,” said Naresh Pandey, a shop-owner who was present to see the party leader take his oath on Wednesday afternoon. “He is a common man and he wants to help the common man.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies