She fled North Korea and turned to online sex work. Then she escaped again

'In the beginning, I didn’t think it was going to be a big deal. I thought it would be okay because I wasn’t actually sleeping with anyone'

Sometimes the men just wanted to talk with the North Korean women. “Face cam,” it’s called. But most of the time, they wanted the other option: “body cam.”

Watching through a smartphone app, the men would ask the women, some of the unknown thousands of North Koreans sold to Chinese husbands and living secretly in northern China, to show their breasts or their backsides, to touch themselves or perform sex acts on one another.

Most of the time, the women did as requested. They needed the money - even if it amounted to only a few dollars a day.

“In the beginning, I didn’t think it was going to be a big deal. I thought it would be okay because I wasn’t actually sleeping with anyone,” said Suh, who, until dreams of escape brought her to this dingy room in Laos, had been one of the legions of North Korean women performing online sex work in back rooms in China. “But then I found out how many perverts there are out there.”

Suh, a 30-year-old who escaped from North Korea in 2008, resorted to doing “video chatting” after her second child was born and her husband’s meager construction earnings wouldn’t stretch any further.

“There are some people who just want to look at your face, but the majority of them are there for their sexual desires,” Suh said, putting her head down so her long hair covered her cherubic face. “I felt so disgusting.”

Together with two women from her village in northeastern China who were also doing chatting work, Suh fled over the summer. She made the heart-wrenching decision to leave her 5-year-old daughter with her Chinese husband.

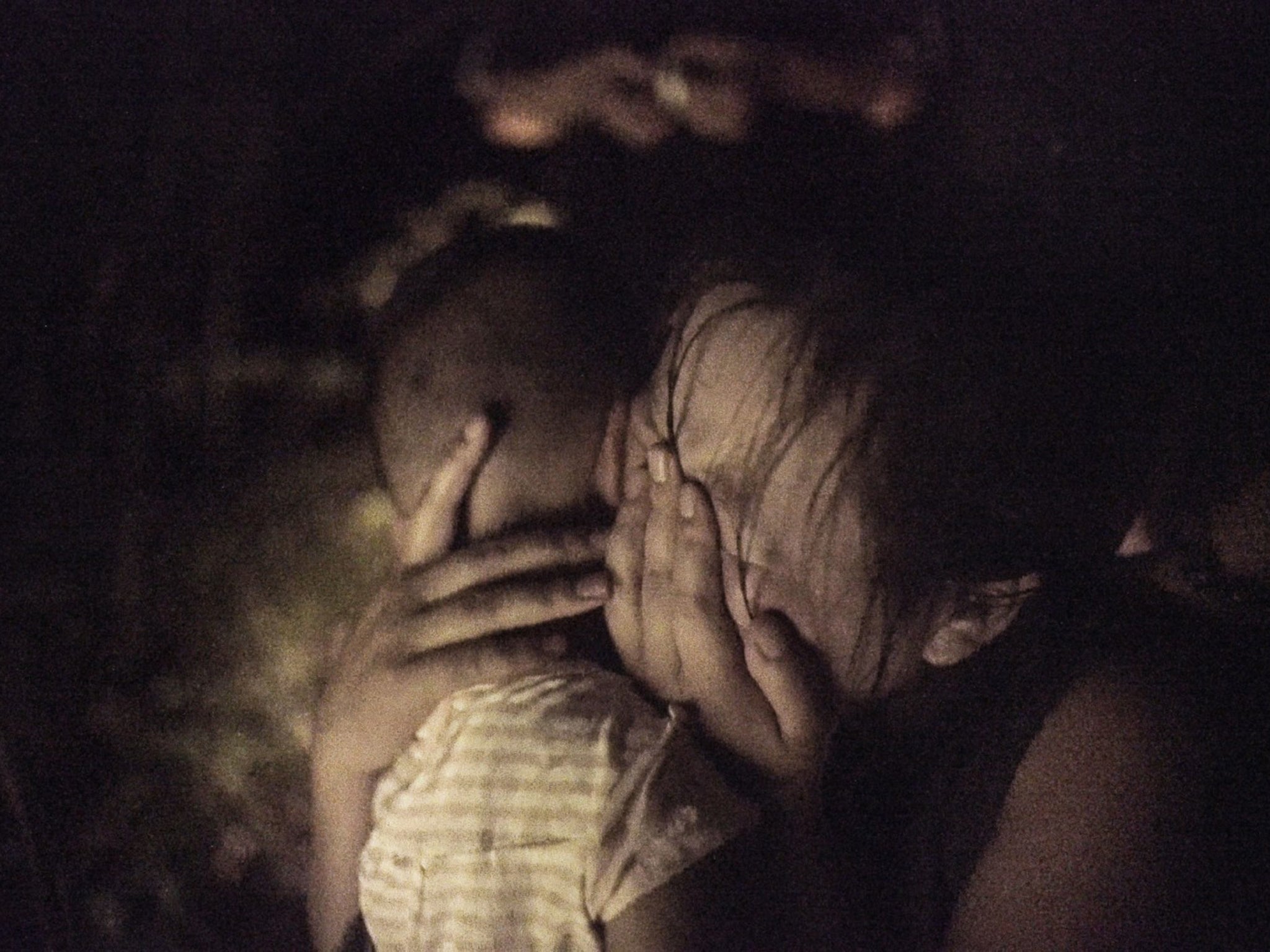

The women traveled by bus and car down through China to the border with Laos, which they crossed illegally in the black of night, Suh carrying her 18-month-old daughter, Ji-yeon, on her back.

The women made it to Vientiane, the Laotian capital, where a Washington Post reporter spent two days with them as they paused on their journey to what they hoped would be a better life. The women talked for hours about their lives in North Korea and in China but, unlike some defectors who exaggerate their stories to make them more sensational, they appeared to play down their experiences, apparently out of shame.

Most of their stories could be verified with the pastor and broker who were helping them escape, and it was clear that the women, faced with no other options, had resorted to performing on camera for men.

The women had a friend film them at work before they left, so they could prove what they had been doing. The videos showed the women - sometimes in brightly colored underwear, sometimes naked - sitting against a low bed covered with a purple Hello Kitty quilt in front of two computers on a low table. Men, sometimes visible, sometimes not, gave them instructions. Most of the men they “chatted” with online were in South Korea, but a few were in America and even Africa.

Safely out of China, the other two women, both called Kim, wanted to get to South Korea, but Suh had her heart set on a more ambitious destination: the United States, “the strongest country on Earth.”

“I think my daughter is one lucky baby,” Suh said, sitting on the bed in a grimy room in Vientiane and looking at Ji-yeon as she slept, snoring lightly. Their few possessions were in plastic shopping bags, save for the clothes drying on coat hangers dangling from the light fittings. The baby had not even one toy. “All the suffering is worth it. Our destiny has changed,” Suh said.

Lives at risk

Defections such as that of Thae Yong Ho, North Korea’s deputy ambassador to the United Kingdom who fled to South Korea over the summer, make headlines because they are so rare. But less sensationally, a steady if diminishing stream of North Koreans is making their way out, down through China, across to Laos, then into Thailand and eventually to South Korea.

Most are women from the northern provinces, considered down-and-out even by North Korean standards, and face an extremely precarious life in northeastern China. Many had been sold - some knowingly, thinking life couldn’t get any worse. But other women had been tricked into thinking they were heading to jobs in China, only to find that the man who offered to help them escape, paying bribes to border soldiers and arranging passage, turned out to be a trafficker, selling the women and pocketing the profits.

The buyers are men in the countryside who are too poor or unappealing to get a wife any other way, and the women are stuck in remote villages where they cannot communicate with the locals - if they are permitted to leave the house, that is.

Since Kim Jong Un took control of North Korea at the end of 2011, security has been tightened, and it has become increasingly difficult to escape. That has driven up prices. Women ages 15 to 25 are the most prized, fetching between $10,000 and $12,000, brokers and humanitarian workers say, while women in their 30s can be acquired for half that.

Increased prices mean that some Chinese families are spending their entire life savings to buy a North Korean woman, and as a result the women are sometimes shackled inside the house.

But even if the women are allowed out and even after they learn some Chinese, venturing into the open is a risky business. If they’re caught by the Chinese police, they face repatriation to North Korea and, at a minimum, time in a labor camp.

“These North Korean women in China faced a dire dilemma, either having to remain hidden and submit to this kind of sexual exploitation, or risk working outside of their residence with the very real possibility that Chinese authorities could arrest them at any time and force them back to North Korea,” said Phil Robertson of Human Rights Watch.

The State Department’s 2016 Trafficking in Persons Report noted that North Korean women and girls “are subjected to sexual slavery by Chinese or Korean-Chinese men, forced prostitution in brothels or through Internet sex sites, or compelled service as hostesses in nightclubs or karaoke bars.”

The State Department reported that the Chinese government “does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking; however, it is making significant efforts to do so.”

Although some women take the risk of working outside the home, shuttling between cleaning and babysitting jobs or working behind the scenes in restaurants, an increasing number feel they have no choice but to try to make money behind closed doors.

That is where video chatting comes in.

Online sex work vs. escape

About one-fifth of the North Korean women living in hiding in China are involved in this kind of online sex work, said Park, a broker who works to get women out.

The Post agreed to withhold Park’s full name to avoid jeopardizing this highly sensitive work. The newspaper also agreed to use the women’s family names only, partly to protect relatives in North Korea.

“If you’re working in a restaurant or outside, you run the risk of being asked for your papers by the police. So doing this work is safer and the money is better,” Park said. “In the village where they lived, every North Korean woman does this. It’s so normal to be doing this.”

Some North Korean women in China are forced into this work, essentially held prisoner by pimps. The women The Post met were not forced, as such. But they had few other opportunities.

Suh was sold eight years ago to a man in northern China who, she said, treated her well - he beat her “only a few times.” But the arrival of their second child made a tough financial situation untenable. She heard about video chatting through a friend of a friend and began chatting with South Korean men at night when everyone in her house was asleep.

On her first day she earned $3. In her best week, she netted $120.

A few months ago, Suh decided she couldn’t take it. “I wondered why I had to do this. I’m a human being, the same as everyone else,” Suh said, breaking down into heaving sobs. “I wanted to be a good mother, a strong mother for my daughters.”

She decided to try to leave, along with the two others. They found out about Park and Kim Sung-eun, a pastor from the Caleb Mission, a church in South Korea that helps bring defectors to safety, and asked to be helped out. For the second time in their lives, they escaped, this time to a safe house in northern China, and from there they made the journey to the border, then walked to Laos.

Laos was safer but still somewhat of a gray area; they may be sent back. Once they got to Thailand, the fear of repatriation to North Korea would be gone.

While waiting to cross the Mekong River, the women talked about the difficult decisions they had had to make. Suh’s 5-year-old is listed on her Chinese father’s family register, which gives her legal status in China and enables her to go to school. But by the time Ji-yeon was born, the back channel for registration - involving bribes to willing officials - had closed. The baby doesn’t legally exist.

So when Suh decided to flee and realized she could only manage to take one child with her, she knew it had to be Ji-yeon. “She thinks I’ve abandoned her,” Suh said, breaking down into another torrent of tears as she recalled telling her older daughter she would be back soon.

The day they were to cross into Thailand, the women were full of nervous excitement. But things soon went wrong. Heavy rain had swollen the Mekong, and their boat missed the drop point.

They were discovered by local police and taken to a prison. They were terrified and sent an endless stream of messages to Park, asking if they would be sent back to North Korea. One photo they sent showed Ji-yeon standing in a cell, looking out through the bars.

Instead, they were taken to Bangkok, where they are now being held at a detention center, the pastor said.

Suh has applied for asylum in the United States, even though she speaks no English and knows she will receive little support, unlike in South Korea. Officials from the American Embassy in Bangkok have met with Suh and her daughter, the pastor said. He estimated that it would take about four months for their asylum claims to be processed.

An embassy spokeswoman in Bangkok declined to comment. The United States has accepted 74 refugees from North Korea since Kim took power, according to State Department data.

During the pause in Vientiane, the relief of being out of China had washed over the women, and the challenges ahead loomed. The women had begun to dwell on the handicaps that North Koreans face. “I have no passport, no papers, nothing,” Suh said. “Why are our lives so different, just because of where we are born?”

The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies