Turkey tightens grip on freedom of expression with new social media law

‘Young people will not forget this and will make you pay the price at the ballot box,’ warns one social media user

Turkey has passed a social media law that human rights groups warn could lead to harsh censorship and further erode the ability of Turks to voice dissent.

The law, passed early on Wednesday with the approval of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and its ultra-nationalist junior partners, forces social media companies with more than 1 million local daily users to set up offices or hire a Turkish representative, and store data inside the country.

Those that fail to comply face fines of up to 40 million Turkish lira (£4.4m), bandwidth reductions and bans on advertising. In addition, platform providers will be responsible for responding to requests for content removal within 48 hours.

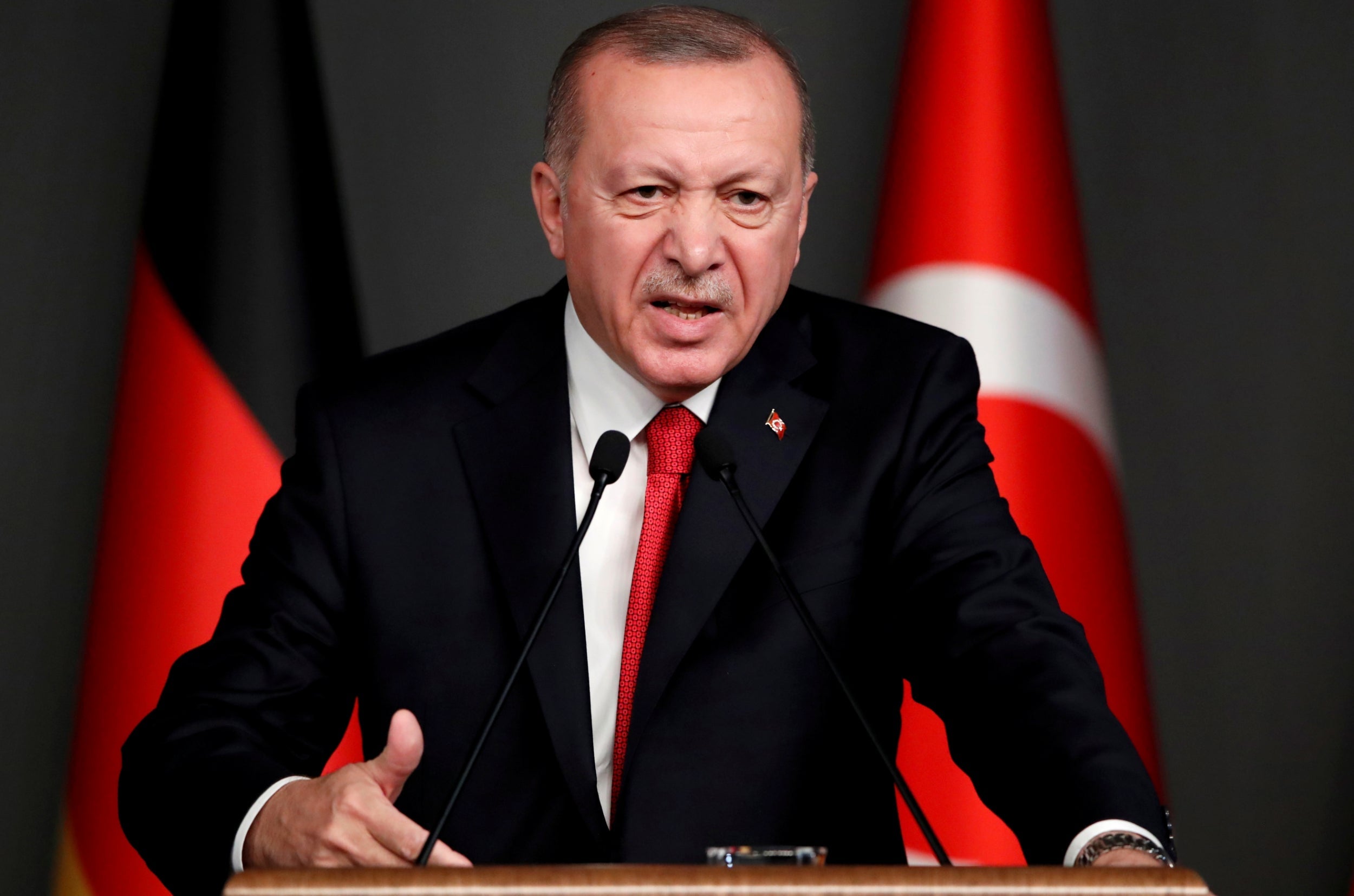

Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, had pushed for the law after his daughter and son-in-law, who is a cabinet minister, were subject to abuse on social media after posting about their newborn child.

Perhaps the most threatening measure is the requirement for social media platforms to store data on individual users within Turkey, potentially giving the government access to the private information of anonymous accounts.

The social media law is part of what critics have described as a harsh authoritarian turn for Turkey under Mr Erdogan. Up to 2019, Turkey had blocked more than 400,000 websites, according to the international freedom of expression group Article 19.

At the same time, the law is emblematic of the government’s frustrations and fumbling in its attempts to control the media narrative. As Mr Erdogan’s allies have taken control of mainstream print and broadcast outlets, young people in Turkey have turned away from them in droves, towards social media and hashtag politics.

One social media user warned that Mr Erdogan was only further alienating Turkey’s youth by attempting to restrict their virtual hangouts at a time of overlapping economic and public health crises.

“The youth of the country does not have jobs,” said the user writing on the wildly popular Eksi Sozluk messaging board.

“Those children have no hope. The only joy left in the hands of those hopeless children is to relax on Twitter and watch things they cannot do due to poverty on YouTube. Young people will not forget this and will make you pay the price at the ballot box.”

A report last year said that three-quarters of Turks under 75 years old were using the internet, and that was before the coronavirus pandemic drove even more people online.

The government has attempted to engage with young people via social media, but has stumbled badly. Mr Erdogan recently gave an interview over YouTube, but his team was forced to shut down the comments as the page was flooded with insults and dislikes.

Twitter last month shut down more than 7,000 accounts it described as state-directed propaganda glorifying Mr Erdogan.

Supporters of the law said that it would shield Turkish citizens from reputational damage. “There is a choice here,” attorney Aydin Egemen told the pro-government news channel CNN Turk. “If the state is a state, no Turkish citizen is different from any citizen in the US or Spain and the state needs to provide full protection. This law provides this.”

The Turkish government is attempting to blackmail tech companies into accepting their proposals. They face either becoming the long arm of the state censorship or having access to their platforms slowed so much that they are in effect blocked in Turkey.

However, domestic and international criticism of the law has been harsh. The International Press Institute said the law is “poised to greatly expand digital censorship and threaten media freedom”, warning that it could lead to prosecutions of critical voices, including independent journalists who have been forced to move to platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and Instagram after being fired or blacklisted from mainstream print and broadcast outlets.

“This law brings the Turkish censorship regime into the social media space,” IPI’s deputy director, Scott Griffen, said in a statement.

Facebook, Twitter and YouTube are yet to comment.

In recent years, social media companies have refused to abide by rules set in countries such Russia, India and Indonesia.

Restrictions on social media have largely failed in other countries. Iranians, faced with draconian censorship on the web, have become experts at using internet tunnelling software to circumvent the bans. Many migrate to messaging-based platforms such as Telegram that are more difficult to control.

“The Turkish government is attempting to blackmail tech companies into accepting their proposals,” Sarah Clarke of Article 19 said in a statement. “They face either becoming the long arm of the state censorship or having access to their platforms slowed so much that they are in effect blocked in Turkey.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies