The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Discovery of new building blocks of life on Ceres suggests a geologically active dwarf planet

A sub-cerean brine reservoir is leaking onto the dwarf planet’s surface, hinting and recent geological processes and an environment that could potential host microbial life.

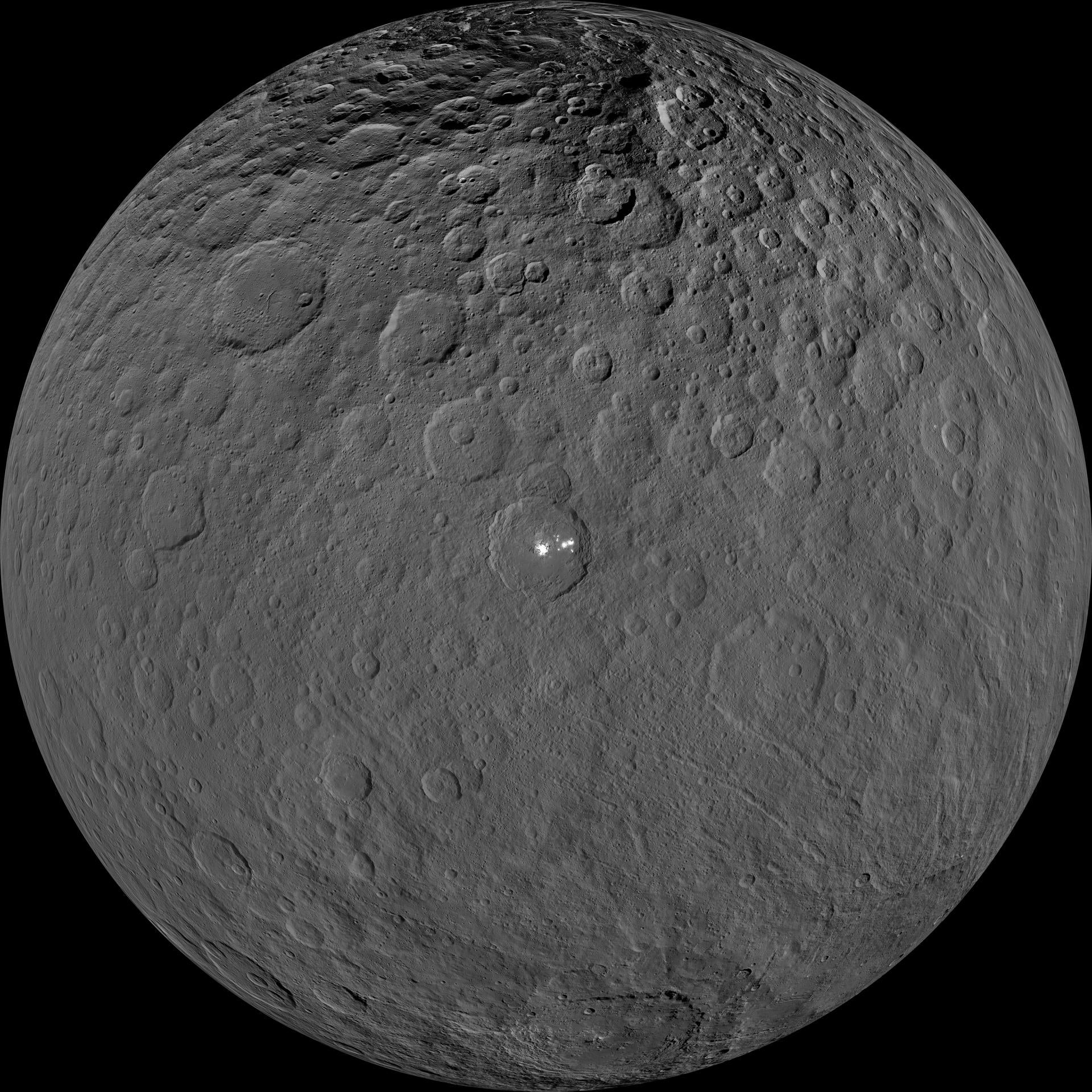

The dwarf planet Ceres is the largest object in our Solar System’s main asteroid belt, and it may be one of the most interesting as well.

A new study has found evidence of organic compounds, the carbon-based building blocks of life, on the dwarf planet’s surface likely originating in a deep aquifer and brought to the surface through geologic processes.

The new findings are not the first evidence of organic material on Ceres. Scientists working on Nasa’s Dawn mission, which visited Ceres, first announced the discovery of organic materials in 2017, and in 2018 scientists added further detail, calling Ceres a “chemical factory” with large amounts of water, ammonium, and carbon in its make up.

At no point have scientists found any evidence of alien life on Ceres, but the rich assemblage of organic materials is nevertheless interesting. As the authors of the new study published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications, Ceres formed early in the Solar System and represents what the embryonic proto-planets that eventually formed into Earth, Venus, and Mars may have looked like long ago.

While previous research on Ceres uncovered organic materials in the Ernutet crater in the dwarf planet’s northern hemisphere, the new study focused on bright material in the third-largest impact crater on Ceres, the Urvara basin in its southern hemisphere. Bright material found in Urvara is believed to be salts and organic material that may originate in a salt brine reservoir deep within Ceres at the dwarf planet’s crust-mantle boundary.

Ceres does not appear to have a molten core, and without such a deep reservoir of heat, the salts may serve to help keep the water liquid in the brine reservoir beneath the dwarf planet’s surface. Such an environment could theoretically host microbial life.

The new study made use of a set of images from the Dawn mission that provide a spatial resolution of around three metres, the first research use of the images, and affording the researchers a relatively detailed look at Ceres’s surface.

The age of the Urvara basin and certain smooth features led the researchers to conclude the salts and organic materials did not seep out of Ceres due to heat from the impact that created the crater but instead rose to the surface due to geological processes. The material could have been uplifted during a process that created a central peak seen in the Urvara crater, or the material might have been seeped out of cracks formed by cryo-volcanism in the region.

“This is the first finding of organic-rich material outside the Ernutet area and its surroundings,” the researchers wrote in the paper. “Our results strengthen the hypothesis that Ceres is and has been a geologically active world even in recent epochs, with salts and organic-rich material playing a major role in its evolution.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies