Muhammad Ali’s latest tribute reminds us that his nobility will endure long after he is gone

The epic third meeting with Frazier in Manila bound the pair for eternity

Muhammad Ali returns to the front cover of Sports Illustrated for the 39th time this month, on this occasion to mark the naming of the publication’s Sportsman’s Legacy Award after him. The announcement was made last week on the anniversary of the “Thrilla in Manila”, that impossibly intoxicating heavyweight world title fight with Joe Frazier in the Philippines, which 40 years on has lost little of its allure or significance.

The cover is arresting, resurrecting Ali at his magnificent, youthful best, pinning the reader with eyes full of mischief and menace. Photographed in timeless boxing pose, the portrait is atmospherically lit, casting Ali in light and shade, and inviting us to reconcile the essential beauty of the image with the primal nature of the subject.

It is a picture adeptly chosen, capturing the profound relevance of Ali’s historic career and a sense of period. Here was a brash, young athlete beginning to understand the power of his own unique brand and the impact he had on an audience that did not quite know what to make of him.

Ali coincided with a tumultuous period in post-war American history, when society was convulsing under the twin assault of civil rights protests and anti-Vietnam sentiment. The conditions were ripe for a campaigning supernova to link the two threads and lead a divided nation towards a new accommodation. None could have foreseen the role that a boxer named after the owner of a cotton plantation in Kentucky would take in that process.

As Cassius Clay, Ali had already introduced a thrilling, new dimension to boxing, bringing to the heavyweight division the ring craft and dexterity of the middleweight. He borrowed many of his moves from the dancing feet of Sugar Ray Robinson, and from the world of professional wrestling added a gauche Vaudeville element set to rhyme, which might be considered a forerunner of rap.

His victory over Sonny Liston in 1964 changed the rules of the game. The interest of Sports Illustrated had already been piqued the year before. “Cassius Invades Britain” proclaimed his first appearance on the cover, a picture of the boxing prince set against Westminster Bridge with Big Ben over his shoulder. Like him, it was funny and irreverent. American sport’s heavyweight journal was all over the next big thing.

Ali could not have done it on his own, of course. Without high calibre duels to draw out his outrageous talent and deep courage, we are left with Floyd Mayweather Jnr, self-proclaimed majesty that carries nowhere near the weight of impartial judgment. The period we associate with Ali’s greatest work arguably came when he was past his peak. We were robbed of the fullest expression of his genus by the three-year ban imposed following his refusal to accept the draft in 1967, inspired by his conversion to Islam.

Ali was stripped of the heavyweight title he took from Liston and would not fight again until 1970. The first duel with Frazier came in his third fight back at Madison Square Garden in 1971. Frazier, who followed Ali to Olympic gold in Tokyo in 1964, stepped into the heavyweight void and was the hero to beat.

The comic insults inflicted on “ugly bear” Liston seven years previously had hardened into bruising political rhetoric by the time Ali returned. The unjust and controversial dismissal of Frazier as an “Uncle Tom” did not just disappoint his opponent. As the son of a South Carolina sharecropper, Frazier needed no lectures from Ali on the inequities of the American way, circa 1970. The barb left a stain that Ali would never quite erase, despite his later apology.

Frazier had a ring in which to respond and duly inflicted upon Ali a first professional defeat. They met a second time three years later, after Ali had lost again, this time to Ken Norton, and Frazier had been lifted savagely off his feet by an entirely new breed of heavyweight, George Foreman. Ali would, of course, resurrect his legend in the “Rumble in the Jungle”. defying the odds with the conquest of Foreman only he foresaw.

And then came the epic third meeting with Frazier in Manila that bound the pair for eternity. It ended after the penultimate round with the words of Eddie Futch, who pulled a partially sighted Frazier, his head grotesquely disfigured, out of the contest. “It’s over, son. No-one will ever forget what you did here today,” Futch said prophetically. Frazier left us four years ago, aged 67. Last month, a 12-foot bronze depicting the left hook that nuked Ali in their first meeting, was unveiled in Philadelphia, a fitting tribute to an all-time great.

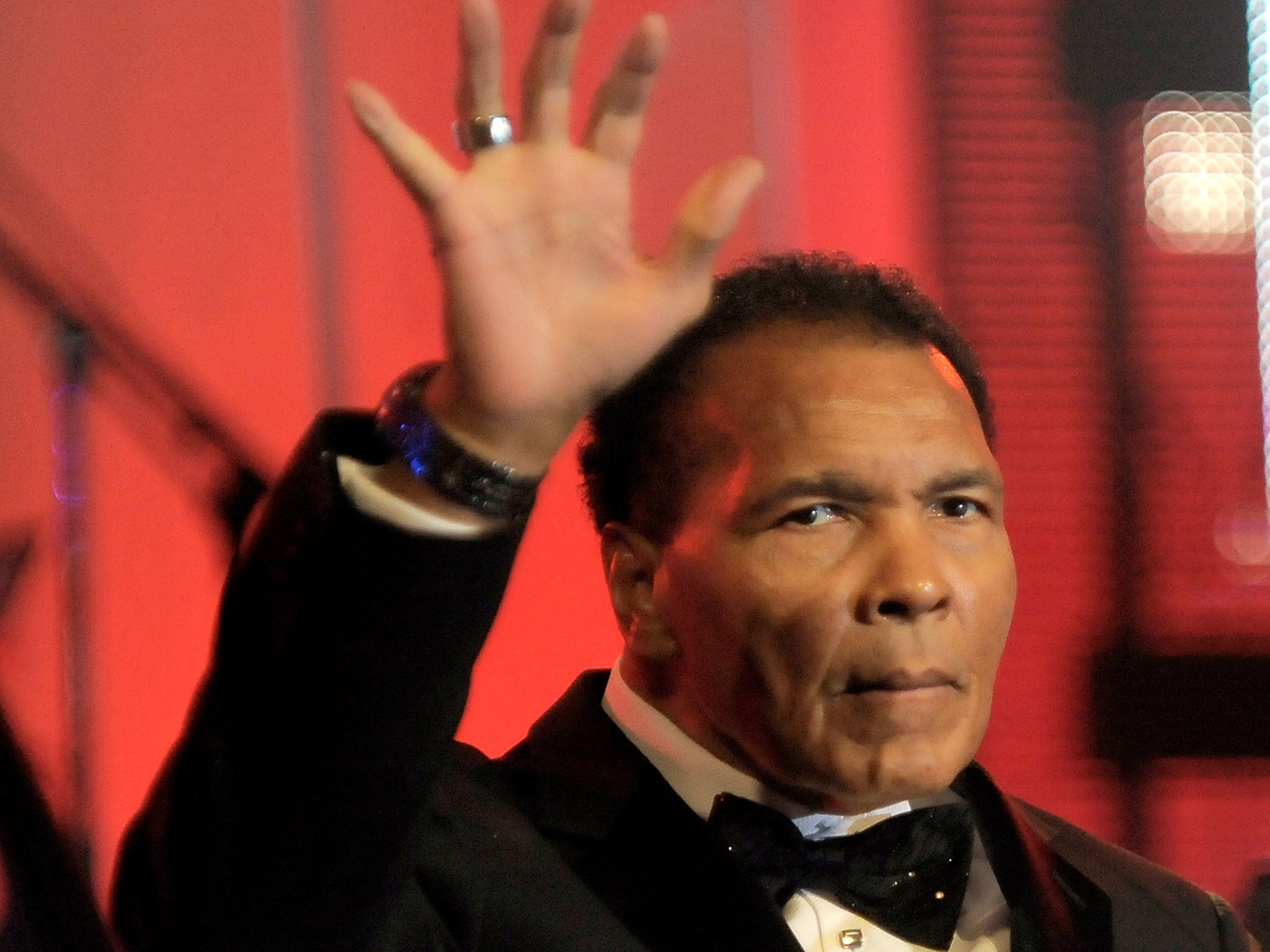

Ali separated himself from the rest by his political engagement as much as his histrionics and his shuffle. Diminished now in the advanced days of Parkinson’s, he attended last week’s ceremony flanked by Foreman and Larry Holmes, who picked over the carcass of the Greatest in his penultimate ring outing in 1980.

Age and infirmity will get him in the end, but not his nobility. That stays with us, an indelible entry in the story of American life.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments