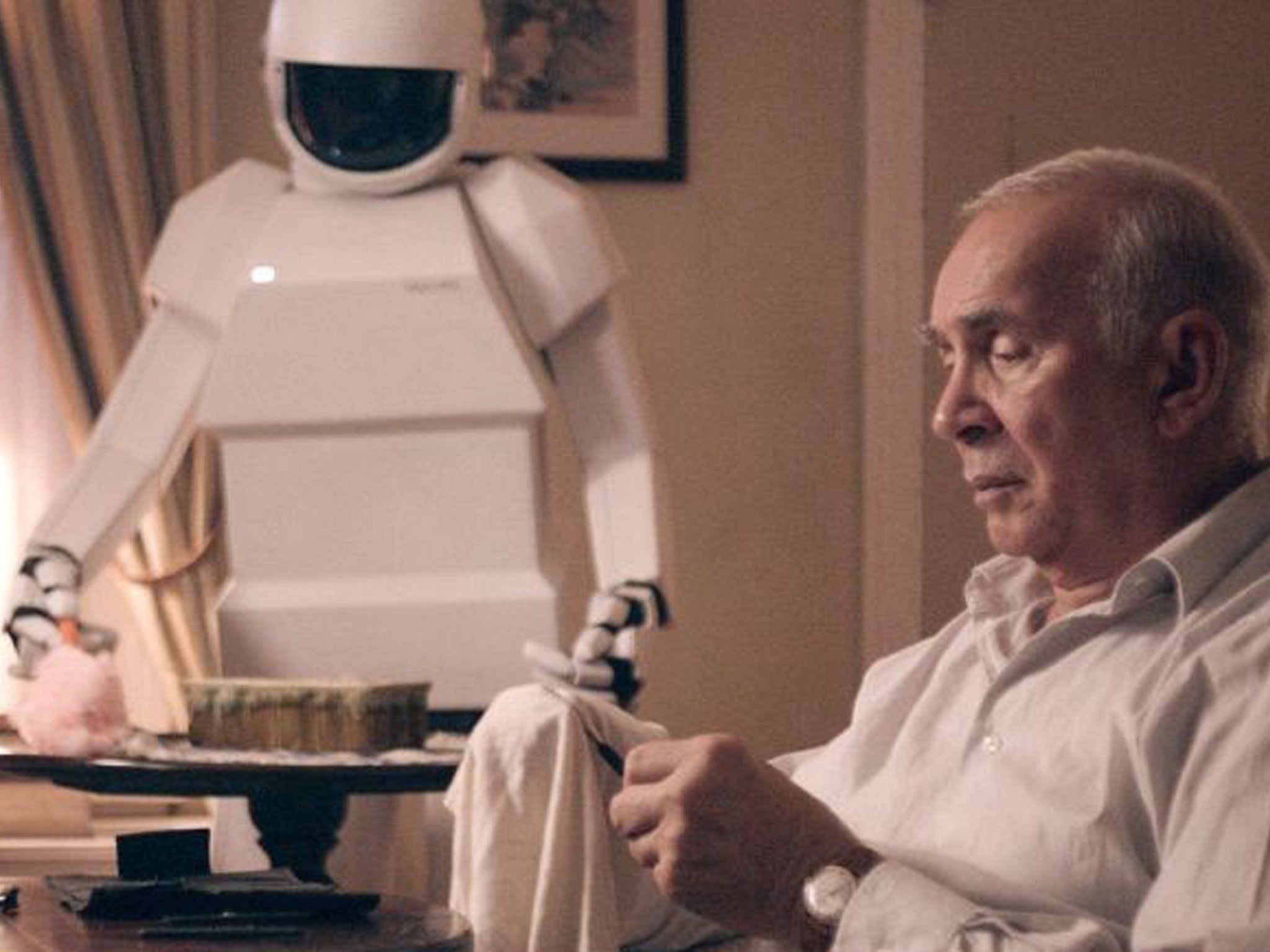

Why does the tech industry ignore the elderly in favour of the Snapchat generation?

Technology has the potential to change the lives of older people. Grow up, says Kevin Maney

The tech industry needs to stop being so dunderheaded about technology for the elderly. For the past decade, the industry has been laser-focused on transforming life and work for one rocketing market segment: 25-year-olds with money. It has routinely avoided, underestimated or remained ignorant about the world's other rocketing market segment: old people and the family members who take care of them.

This is personal. I have parents who could really use new ways of dealing with issues such as memory loss, immobility, shrinking social circles, boredom and, of course, escalating healthcare needs. I've searched for products and services that would be truly helpful and built for them, not built for the life-hacking, smartphone-glued, Snapchatting crowd. I'm frustrated with how little I can find.

A lot of indicators suggest that not much is coming anytime soon either. The monstrous Consumer Electronics Show took place earlier this month in Las Vegas in the US. Roaming the event, you might have found the SmartyPans connected frying pan (it will tell you what you're cooking! Woo-hoo!) or the Digi-Sense diaper monitor (data about your baby's farts – seriously). But you'd have been hard-pressed to find something built for seniors. "It was pathetic," says Laurie Orlov, a campaigner for the elderly who monitored the event for her Aging in Place Technology Watch blog.

Or look at the list of tech unicorns – the 144 companies pumped so full of private funding that they're each worth more than $1bn. Not one is focused on what's being called "ageing tech". It's not a business that makes venture investors salivate.

Gadget and tech news: In pictures

Show all 25"Venture capitalists are too busy investing in Uber and things that get virality," says Ashfaq Munshi, a former Yahoo chief technology officer and IBM Research scientist who, at 54, has become interested in ageing tech. "The reality is that selling to older people is harder, and if venture capitalists detect resistance, they don't invest."

The age of tech entrepreneurs doesn't help. Data collected by Harvard Business Review put the mean age of a tech company founder at 31, and most are between 20 and 34. Entrepreneurs are told that the best way to start a company is to solve a problem they understand. It makes sense that those problems range from how to get booze delivered 24/7 to how to build a cloud-based enterprise human resources system – the tangible problems in the life and work of a 25- or 30-year-old. But for them, the trials of older people are too distant – the stuff of grandparents who probably live far from Silicon Valley.

It's not that nothing is being done. The old "I've fallen and I can't get up" device has blossomed into a whole herd of wearable emergency-calling gadgets. Seth Sternberg, a smart – and older – entrepreneur who sold one company to Google for £70m, has raised £14m to start Honor, a cloud service that co-ordinates care for an ageing person. But you can count the developments that really matter on a couple of hands – if you discount the borderline ridiculous products such as SingFit – as if anybody's going to convince my stepfather to belt out "Let Me Call You Sweetheart" as a way to improve his brain.

But at least a growing cadre of people like Munshi see that it's time to mobilise for the ageing tech opportunity. Technologies such as artificial intelligence and virtual reality are starting to get good enough to transform the experience of ageing.

Munshi is beginning work on a home-listening device that would be the descendant of an Amazon Echo or Apple Siri. It will use machine learning to be able to understand spoken words and put them in context. For an older person, the device would bypass the need to navigate a smartphone or website – an impossibility for someone with Alzheimer's or dementia. Just say, "I want to talk to my son," and it might open a video call on the TV screen. Someone with memory loss might not remember where his wife went or how long it will be until she returns. Ask the question and the system could answer. Just by listening to the way a person talks and comparing it to past conversations, the system could identify problems such as a small stroke or worsening memory loss. "It's within reach to solve that kind of problem," Munshi says.

The possibilities expand from there. In the next decade virtual-reality glasses will get smaller, simpler and much better, to the point where an isolated elderly person could more naturally visit family or socialise with contemporaries without moving from the couch.

Combine technology such as Hearbuds with GPS and facial recognition technology, and older people could get reminders in their ears about where they are and who they are talking to.

Driverless cars should be a giant leap for older people. To stop driving is to give up the freedom to go out to lunch or visit a friend at any time; that limitation ends with driverless cars. You could be 100, nearly blind and have the reflexes of a Galápagos tortoise, but you could whistle for your Google car and tell it to take you to the nearest speakeasy.

Wearables can be geared more to people at risk of falling instead of those wanting to track how far they run, and they could alert family members to changes in gait and monitor other vital signs for trouble.

On the healthcare front, the big advance might be the virtual doctor visit, erasing the difficulty of getting to a clinic or office. Devices will be able to read any vital sign the doctor needs, and HD video can allow the doctor to see anything. Such services are already emerging – they need to be improved and tailored to less tech-savvy users.

Put these developments together, and it's possible to make the experience of getting old radically different a decade from now – as different as it is to be young in 2016 compared with being young in the dark ages of 2006, pre-iPhone. Imagine existing as a teenager when all you could do on a phone was text.

In the meantime, let's hope Digi-Sense never expands into the adult nappy market. There are some things about our parents we don't want to know.

© IBT Media

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies