Chris Blackhurst: How the Sultan of Berkeley Square fell off his throne

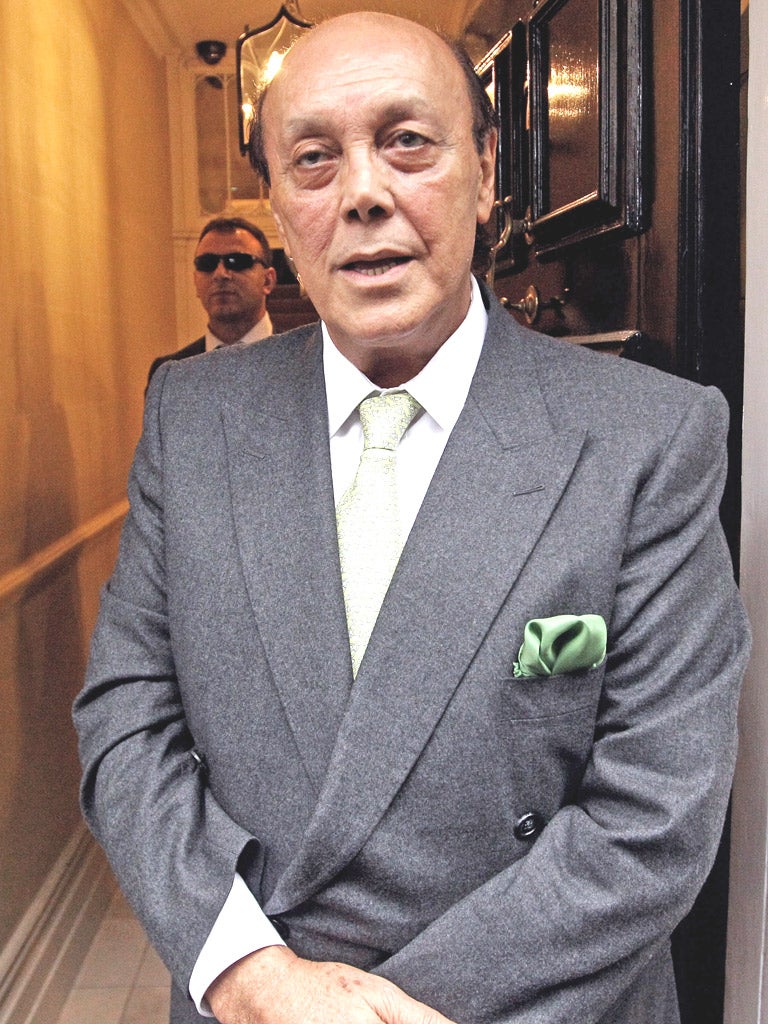

There was a period when the City was transfixed by Asil Nadir. He was the poster boy of the Thatcher generation, whose rise followed her own and seemingly stood for the same values of hard work and enterprise.

In less than 10 years, from 1982, he built a business empire – turning Polly Peck from a company with a stock market value of just £300,000 to one of £1.7 billion. Investors clamoured to grab a part of his success – the Square Mile was littered with tales of Polly Peck shareholders who had become multi-millionaires on the back of a punt of a few thousand pounds.

He was a huge figure, so big that if he had still been operating in London decades later he would have given Alan Sugar a run for his money as the frontman for The Apprentice. He was that large: employing tens of thousands of people worldwide, living in a house in Belgravia and a stately home in Leicestershire, flying everywhere by private jet (this in the days when such things were relative rarities), and owning racehorses.

There was something exotic about him: his office in Mayfair earned him the nickname of the Sultan of Berkeley Square (before that, I remember meeting him on the eastern edge of the City, where Polly Peck occupied an imposing office block).

Looking back, there were clues as to what was to come. He appeared to have the gift of alchemy, turning mundane activities into FTSE gold. His first, serious venture was Uni-Pac, a company that made corrugated cardboard boxes to hold fruit from his native Cyprus. You would not have thought it could produce much in the way of profits: for Nadir it was a cash cow, generating millions a year.

He did it again with bottled water and shirts, each time growing the firm to stellar proportions. With Polly Peck, his main holding vehicle, he created a vast conglomerate to match that of another Thatcher hero, Lord Hanson. TVs, video recorders, air-conditioning units, microwaves, washing machines, fresh fruit and vegetables – you name it, Nadir was into it.

Yet when asked how, exactly, he had a skill that others, also in the same line of ordinariness, lacked, he was vague. There is a City adage that if something is too good to be true it usually is. Yet for all that apparent wisdom, the City also has a habit of not wishing to explore the detail, of basking in a constantly rising share price rather than demanding the answers to awkward questions.

Like the late Robert Maxwell, Nadir’s organisation was built on sand, and like the former newspaper tycoon, he was moving cash around his empire to give the illusion of financial health.

At the same time, assets were being siphoned off to Northern Cyprus. When the pressure grew too much, after Polly Peck duly collapsed and those shareholders who remained and the employees lost everything, and following the bringing of charges against him for false accounting and theft, that was also where he went.

Why do I think he came back? Because he thought he could get away with it. He’d done it before and he calculated that memories were short. On this occasion, for once, his confidence in his own ability to hoodwink was misplaced.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments