The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Robots are going to make England’s north-south divide even worse

There’s a solution to the crisis and it’s one that benefits everyone – we need to work less hours

There’s a lot that distinguishes the north and south of England – from whether you call a sandwich a bap or a barm, or your weekly wash a bath or a barrrth.

Accents aside, there is a very real problem of wealth disparity between the two. Regional inequality in the UK is already the worst in Europe: the gap between the richest and poorest region in the UK is wider than the gap between the richest and poorest region in any other country within the EU. This divide is reflected in significant health inequalities, with one report suggesting that those living in the North of England are 20 per cent more likely to die early.

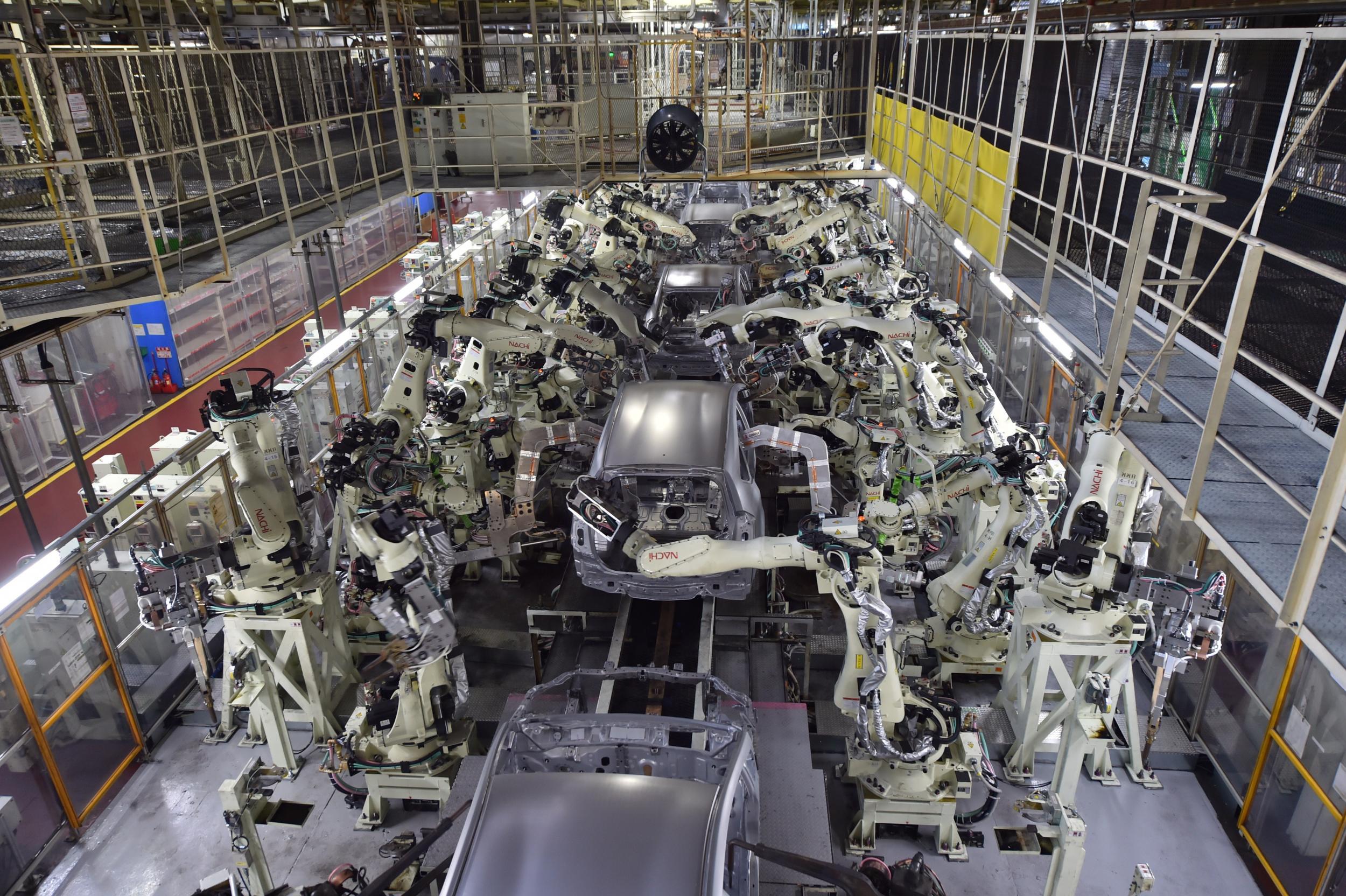

And robots are going to make this a hell of a lot worse. It is being reported that 30 per cent of existing UK jobs could be impacted by automation by the early 2030s. Another report has found that the highest levels of future automation are predicted in Britain’s former industrial heartlands in the North of England as well as the Midlands and the industrial centres of Scotland.

To avoid a crisis in unemployment in the north of England, action has to be taken to deal with the expected impact of automation. The creation of a successful Northern Powerhouse will be dependent on more than the injection of investment into particular projects. To create more jobs and training opportunities, those with fulltime jobs must counter-intuitively work a little less to open up opportunities for those looking to enter the workplace.

The shorter working week is one way workers can take back control of their time in an effort to avoid a 1980s-style crisis. In times of crisis, workers have historically demanded a shorter working week in order to reduce unemployment through the sharing of available work. In 1919, workers in Scotland demanded a 40-hour working week so that discharged soldiers coming home from the War could find employment.

More recently, German unions fought for a reduction in work hours to reduce unemployment, increase job security, and provide more opportunities for training. This was a major reason why unemployment remained so low in Germany after the 2008 recession, despite experiencing an even deeper fall in GDP than the United States.

In the UK, workers are attempting to avoid a crisis by fighting for a shorter working week and taking control of their time. The CWU – who represent 134,000 postal workers – are negotiating for four key demands, including a shorter working week. The demand for a reduction in working hours is a direct response to the impact of automation on postal workers.

A shorter working week could also play a role in increasing productivity in the UK and strengthening the economy at large. We can learn from countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden – all of whom work fewer hours and have higher levels of productivity.

To provide an example from Sweden: at Toyota service centres in Gothenburg, working hours have been shorter for more than a decade. Employees moved to a six-hour day 14 years ago and have never looked back.

From a 7am to 4pm working day the service centre switched to two six-hour shifts with full pay, one starting at 6am and the other at noon, with fewer and shorter breaks. As a result of this change, staff wellbeing increased, turnover decreased, efficiency rose, and profits increased by 25 per cent. Since shortening working hours, productivity in the service centre has increased. Mechanics now produce, in 30 hours, 114 per cent of what they used to produce in 40 hours.

Whether workers will be able to achieve a shorter working week is a question of power, not of affordability. Productivity has steadily increased in developed economies over the past 40 years, whilst wages have flat-lined. One of the effects of this has been to make it harder to work fewer hours: since the 1970s, work-time has barely reduced, despite an increase in productivity by a factor of 2.5.

Germany and the Netherlands have some of the lowest number of hours worked per year in the world, and some of the highest levels of GDP per person, demonstrating that shorter working hours are entirely feasible.

This is a problem of distribution: the benefits of productivity increases are being hoarded by an ever-smaller group of people. If those benefits were shared around more equitably, and wages were to increase in line with productivity increases, we would all be able to afford to work a little bit less.

The North has an illustrious history of trade unionism and with it, the collective struggle for the 40 hour week. For a prosperous future, it must be inspired by its past and once again lead the call for a shorter working week.

Aidan Harper is a member of the 4DayWeek Campaign. Check out the 4DayWeek Campaign at: www.4DayWeek.co.uk or on Twitter @4Day_Week

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies