I predicted this fall in immigration – here's how it should change the Government's Brexit strategy

Whatever your views on the impact of immigration, it cannot be good news that the UK is a less attractive place to live and work, and that we will be poorer as a result. But this need not continue

A year ago I wrote that immigration to the UK might, after the Brexit referendum – but even before Brexit actually happens – fall much faster than anyone expected. As I said then, “migration is not just a matter of the UK choosing migrants; migrants have to choose us. Even if we wish to remain open to skilled migrants from elsewhere in the EU post-Brexit, they may not choose to come here (or remain here).”

So it has proved. Not only has Brexit not happened yet, but the Government has made it clear that free movement will continue, for all intents and purposes, until 2021. But the latest ONS migration statistics show that the UK has become a less attractive place for European migrants.

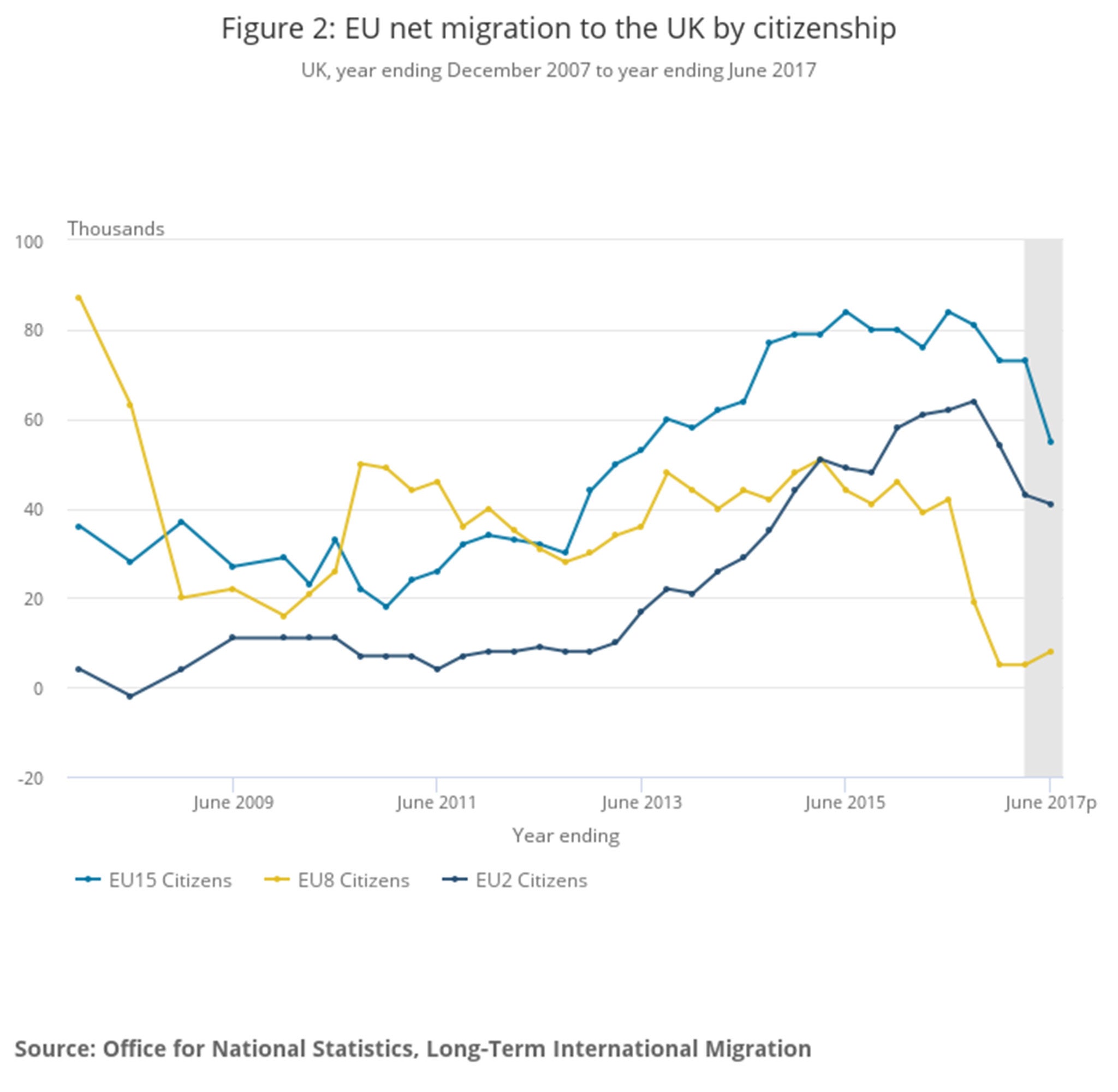

More Europeans are leaving while fewer are arriving, meaning net migration from the EU has already dropped by more than 80,000 – a fall of more than 40 per cent, comparing the year before the Brexit referendum to the year after it.

Confirming this, we have also seen a significant drop in new registrations for National Insurance numbers by EU nationals – a better and more timely measure of those arriving here specifically to work. These are down 13 per cent in the year to September, led by a fall of almost a quarter in registrations from the “EU8” countries who joined the EU in 2004.

What explains this fall? The causes are both economic and psychological. Since Brexit, the UK economy has slowed significantly, and the pound has fallen; both factors make the UK less attractive. At the same time, the rest of Europe is doing much better.

But it’s not just economics. It is hardly irrational for European citizens – whether they are here already, or contemplating a move – to feel less positive about the long-term attractiveness of the UK.

In research published last year, I projected that the impact of Brexit might be to reduce net migration to the UK by 90,000 to 150,000 over the next few years. While such projections are highly uncertain, today’s figures are broadly consistent with that.

I also concluded that such decreases would have a significant negative impact on both GDP and more importantly, GDP per capita. This will also, as the independent Office for Budget Responsibility has pointed out, worsen the fiscal position, meaning less money for public services.

Whatever your views on the impact of immigration, it cannot be good news that the UK is a less attractive place to live and work, and that we will be poorer as a result. But this need not continue.

While some damage has been done, it is far from irreparable. Talk of a “Brexodus” is overstated; indeed, while some EU citizens have left, many others have applied for British citizenship or residency status, with applications for the latter up more than four-fold.

Moreover, while it is certainly true that immigration concerns played a major part in the vote to leave, concerns have fallen back sharply since. Theresa May’s emphasis on reducing immigration, no matter what the economic cost, was hardly an electoral triumph. It may well be that, as British voters realise that reducing immigration is not just an abstract issue, but has large and visible costs – to the economy, to the public finances, to the NHS – there is a window of opportunity to reshape the political and policy debate in a more positive direction.

So what should the Government do? The first priority should be action to secure the rights of EU citizens living here – as Theresa May promised in Florence but failed to deliver.

More important, however, would be to clearly signal that we will have a liberal, humane and economically sensible immigration policy post-Brexit – not one that is, as now, driven by arbitrary and irrational targets, that seeks to stop British citizens from living with their spouses or families, or that seeks to create a “hostile environment” for those coming here from abroad. Nor one that relies on central planning from Whitehall and Westminster, or excessive bureaucracy over who employers can hire or who immigrants can work for.

If, after Brexit, we really want to make a success of “global Britain”, that will mean being more, not less, open to immigration.

Jonathan Portes is a senior fellow at The UK in a Changing Europe research group and professor of economics and public policy at King’s College London

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies