The tortured artist is a dangerous myth. It's the way creative workers are treated that causes breakdown

Having a creative career can come at a high price, so much so that it has become normal to see pain as an essential ingredient for art

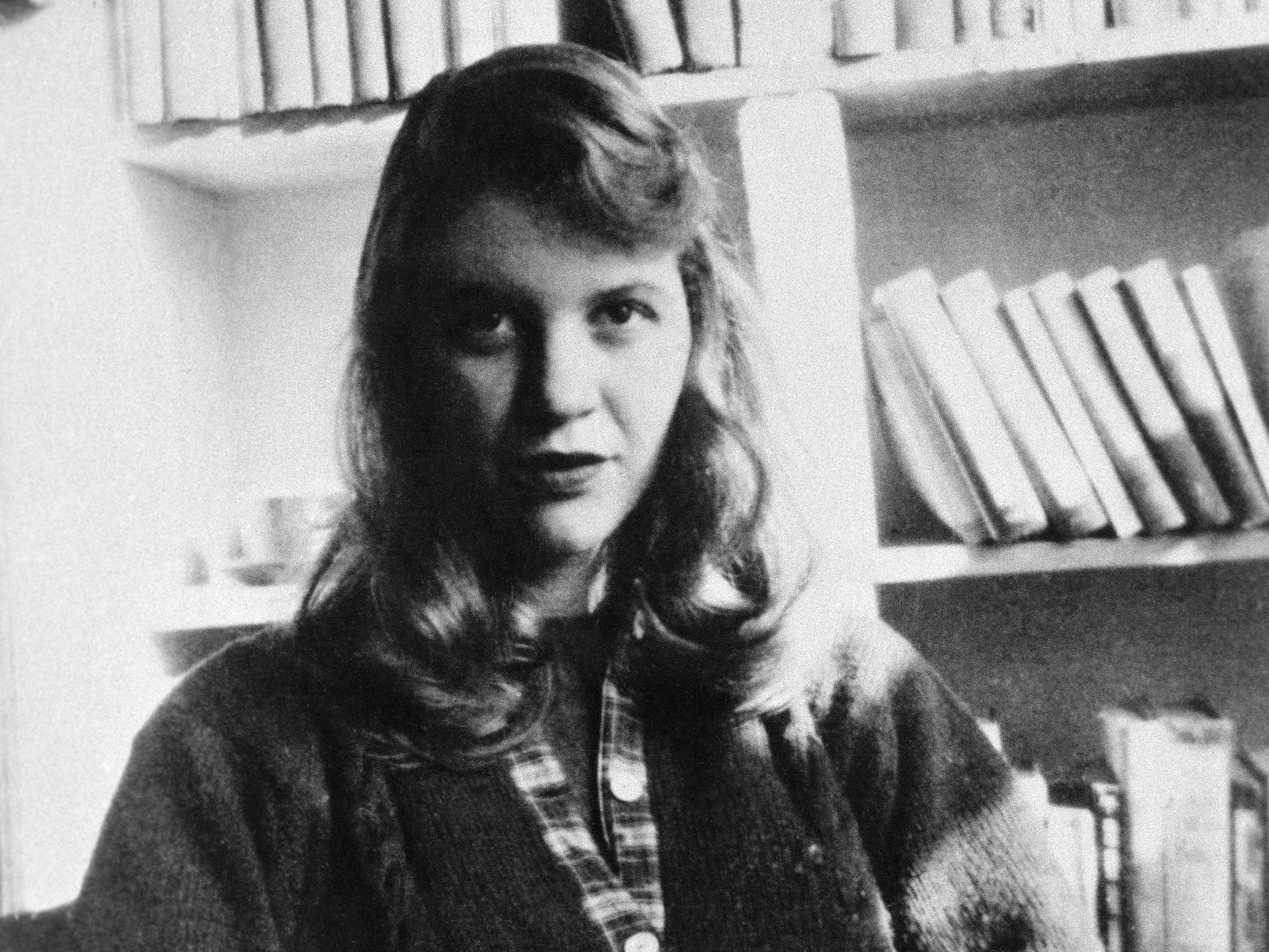

“Turn your pain into art”: it’s a phrase most of us have heard before. Van Gogh painted “The Starry Night” while battling anxiety and addiction; Sylvia Plath died by suicide by putting her head in a gas oven, her death eerily predicted a month before in her only novel The Bell Jar; Frida Kahlo obsessively painted her pain, physical and emotional.

History is full of long-suffering creative geniuses. The list is so long, in fact, that it has become normal to see pain as an essential ingredient for art. “Tortured artists” – a stereotype that we still attach to celebrated musicians, such as Amy Winehouse and Kurt Cobain – are considered to produce the best masterpieces.

The theory that achieving something great requires suffering dates back to ancient times. The Greek myth of Philoctetes tells the story of a man who as a result of a wound, is exiled on an island, and during that time he invents the bow and arrow from scraps of material he finds in a cave. His invention becomes an important weapon used by the Greeks in their battles. Philoctetes is a figure who exists in the margins, much like all artists. His wound (a symbol of his emotional suffering) is the reason he is excluded from society but also seen as the facilitator for his invention, which in turn fulfils his deep longing for social acceptance.

Pain, however, is less an artistic necessity and more a result of “contagion” – a term used for the spreading of a harmful idea or practice. Social contagion refers to the way in which ideas, emotions and behaviours spread from person to person. In the context of the struggling artist, it allows mental illness to fester; to be glamourised and admired; even encouraged in the name of art.

Creativity or creative careers do not, in themselves, cause mental health problems. Nor do mental health conditions necessarily spread from artist to artist, claims Professor Victoria Tischler, an expert in art and health at the University of West London, but working in a creative environment can certainly affect mental health and lead to the spreading of the tortured artist ideal. The creative sectors are rife with poor conditions and high-pressured environments, not to mention low wages, long hours, unstable employment (particularly in times of austerity), and bullying that allows mental illness to remain hidden or seen as under-performance.

Earlier this year, a study by the Inspire Wellbeing charity and Ulster University found that creative workers were three times more likely to suffer from mental health problems. Having a creative career can come at a high price: 60 per cent of creative workers who took part in the study spoke of having suicidal thoughts. Many artists, writers and musicians suffer untimely deaths, some of which could presumably have been prevented if mental illness wasn’t so romanticised by society and seen as an inherent part of creative self-expression – a pattern that musician Jeff Tweedy (who suffered from drug addiction) described as “a destructive myth”.

Every picture tells a story. Some are painted with words, on canvas or through a song. Whatever their medium, artists have long spoken of their plight through their work. We must, at long last, hear them.

After all, what is art if not an expression of humanity? It is time to show some of that back to its creators.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies