King Charles and Queen Camilla: How an imperfect perfect relationship became our Trump card

It has certainly not been easy but, writes Tessa Dunlop, after 20 years of marriage, there is something undeniably moving about the triumph of a couple whose commitment to each other has morphed into a symbol of strength. And in a world of Trumpian-induced chaos, is more needed than ever

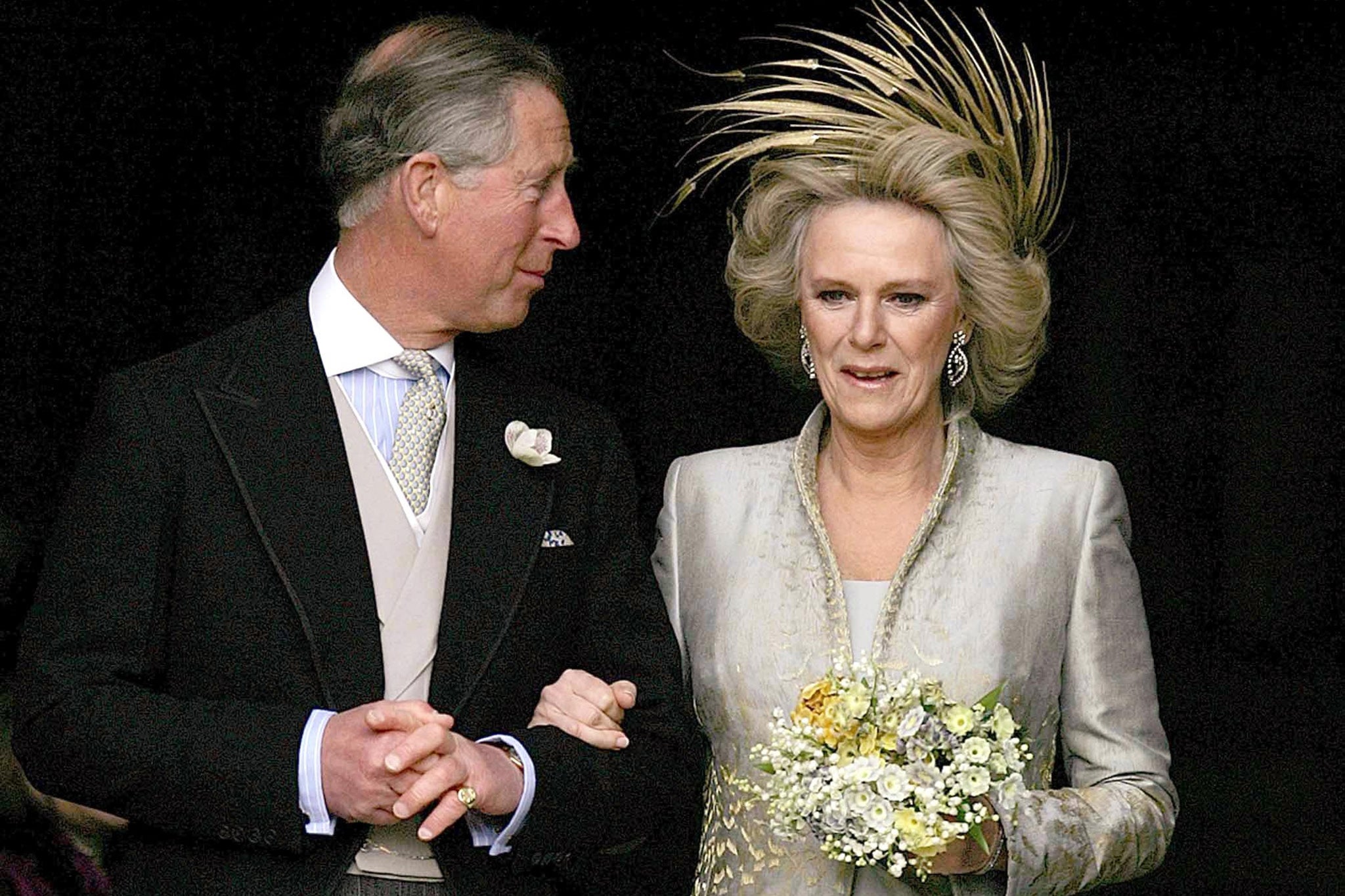

Arm-in-arm, relaxed and happy in the spring sunshine, Charles and Camilla smiled for the cameras on the first day of their state visit to Italy yesterday. The scene is a far cry from the billowy April day 20 years earlier that marked the beginning of the King and Queen’s married life. Back in 2005, it was not weather for fly-away headgear but Camilla had no choice.

Only royal brides who tie the knot in churches are blessed with heavy-set tiaras – Charles’s second wife had to make do with golden feathers. A hand was required to clasp them to her head; the Queen, standing two steps above, muttered something – perhaps “I told you so”?

Camilla smiled and Charles dodged a feather in the eye. But at least their nuptials had been blessed, by God, in St George’s Chapels, and by the late Queen’s (fleeting) presence. Her Majesty turned up at the end, after the actual wedding in Windsor Guildhall. It would never do for the defender of the faith to ally herself too closely with the younger generations’ mistakes. Poor Camilla. Even Harry felt a begrudging sympathy in the build-up to the big day.

In Italy two decades on, the couple are unlikely to have their planned audience with Pope Francis due to the latter’s ill health. Twenty years ago, his predecessor’s death delayed the royal wedding, another hitch in the star-crossed lovers’ long journey. Young Harry recalled the wedding had to be delayed, again: “Bad karma. Less press. More to the point, Granny wanted Pa to represent her at the funeral.”

Charles’s dissenting son wondered if “some force in the universe [Mummy?] was blocking rather than blessing their union”. He wasn’t the only one. In April 2005 Charles and Camilla’s wedding felt endured rather than celebrated. For many of us, it passed without comment. Memories of Diana were still painfully fresh, and Camilla was an uncomfortable reminder of the messy, modern age of affairs and divorces, that most preferred not to associate with monarchy.

For much of the 20th century, the Windsors were sold to the public as the pin-ups of moral probity and romantic wedded bliss. Who can fail to recall, scene by scene, the wedding of Lady Diana Spencer to our future king in the summer of 1981?

This was a replay of Elizabeth and Philip’s fairytale wedding of 1947, but on a far grander scale. The Duke of Edinburgh was reputedly delighted: his son in an honorary naval uniform walking an innocent virginal bride down the aisle into a bright royal future. At least, so we were all led to believe. With a wedding dress that enormous, what could possibly go wrong?

Yet even then, there was generational disquiet. As the carriages trundled across the television screen like large prams I distinctly recall the adult conversation going on over my head: “Poor Queen, she will be upset that Diana’s parents had such a nasty divorce. She’s a great believer in marriage.” But what kind of marriage?

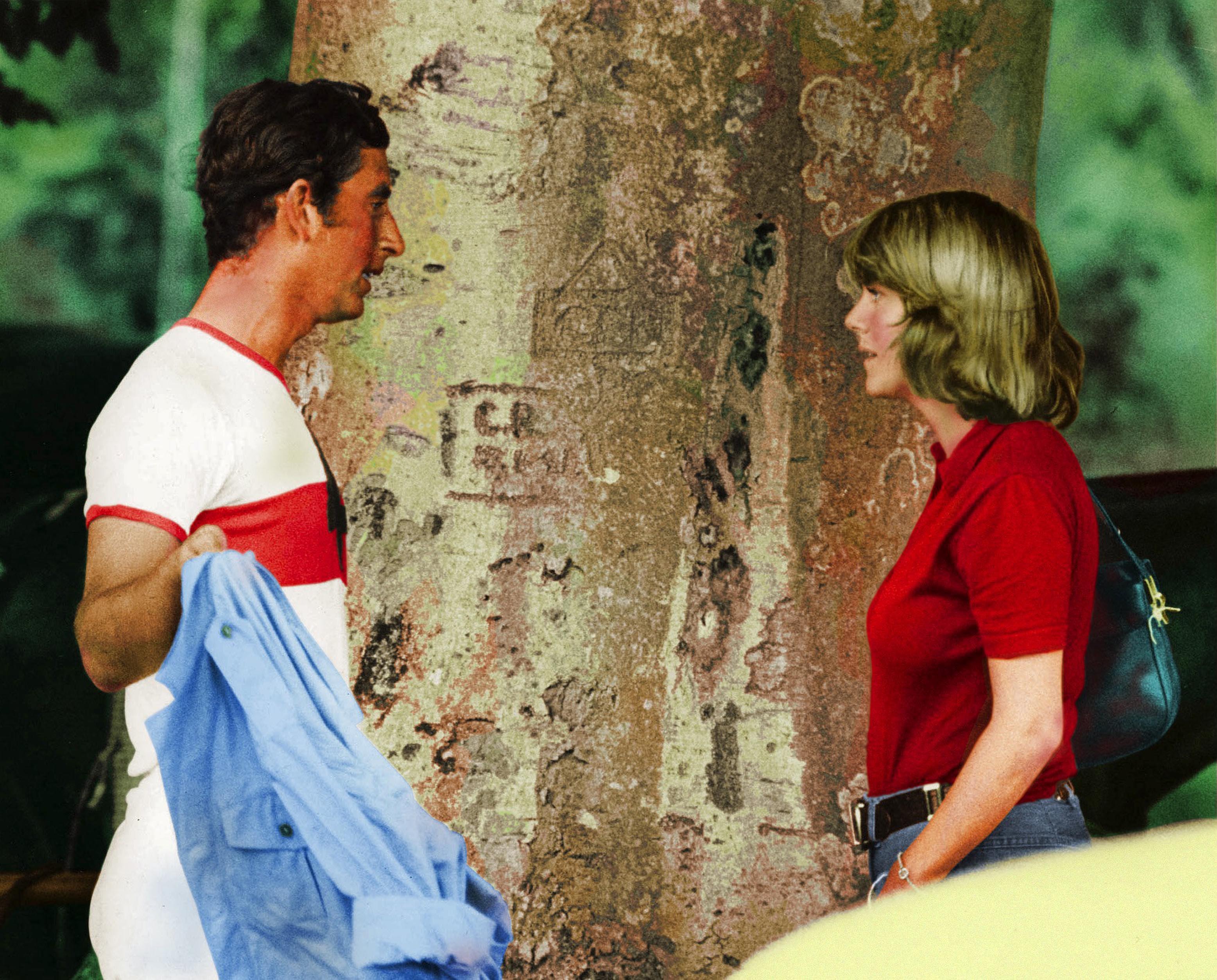

When Charles and Camilla first met, (a polo match apparently, in 1970) apocryphal stories of Camilla joking about her great-great-grandmother Alice Keppel’s affair, with his great-great-great-grandfather, Edward VII, abounded.

After all, as historian AJP Taylor once observed, aristocrats do things differently. Deep into the 20th century, while the rest of the population was getting used to the idea of a companionate marriage, among the upper classes, marriage still centred around property, progeny and propriety – love came much lower down the list.

Small wonder then that Charles thought he might be able to game the system, marry a royal-appropriate bride in Diana and privately hanker after his true love Camilla, long since hitched to another man. With the monarchy still an institution that has foregrounded tradition, it is perhaps unsurprising that the social changes of the Sixties and Seventies appeared to impinge little on royal thinking.

Updated divorce laws in the late 60s brokered a brave new world where a man and woman could go their separate ways if a love match became a mismatch. But in 1992, long after Charles and Diana’s union had so visibly and painfully hit the skids, prime minister John Major informed the House of Commons the couple would separate, not divorce.

This was the Queen’s annus horribilis; we will never be privy to what she called the subsequent years of televised tell-alls and tragic deaths.

The road to Charles and Camilla’s wedding day was a long and rocky one. Despite the well-established precedent that the King’s wife becomes Queen, the public were informed that Camilla would make do with consort in her title.

At the time, it belittling reminder that this second bride would be a second-rate sort of Queen. Looking back it feels silly and cruel. Elizabeth II finally caught up with changed social mores when she announced Camilla should be known as Queen upon her son’s ascension to the throne in 2022. A whole 17 years after Charles’s second wedding, his wife had finally received the ultimate royal seal of approval.

The public were quick to follow suit. If Camilla was good enough for Her Majesty the late Queen, she was good enough for us. These days, cast through a more flattering prism, Camilla’s enduring commitment to her vulnerable husband has become more than acceptable, it is an essential ingredient in the royal merry-go-round.

Today, the king is an old, unwell man who needs support. It was perspicacious of him to realise he had to have Camilla by his side, that he couldn’t serve without her. Rather than a blot on the royal copybook, their checkered backstory and resolute love is a reminder that human frailty and mistakes do not preclude happy endings.

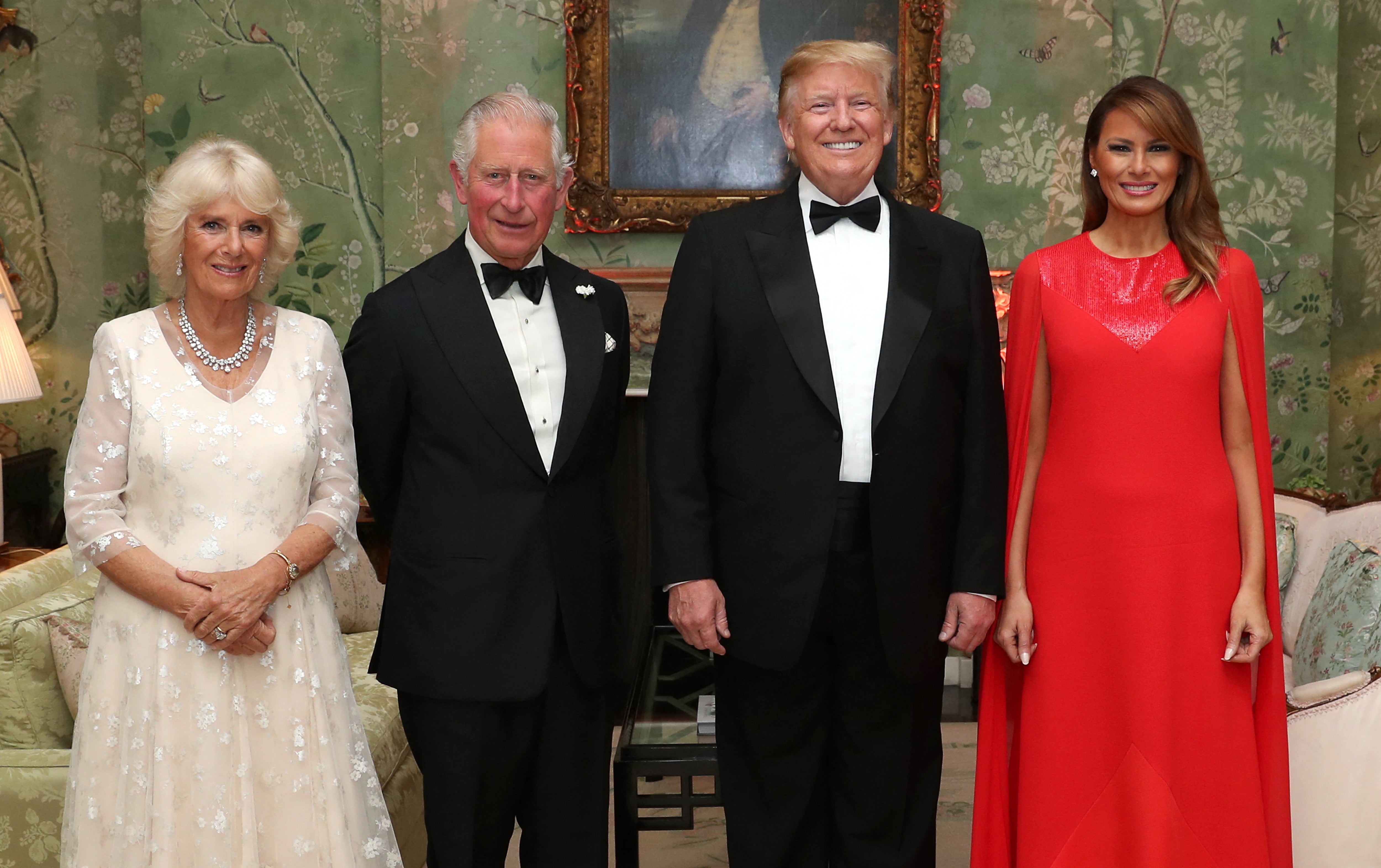

Amidst the current turmoil, the prospect of bombastic rule-breaker president Donald Trump having to sit down beside our tender King, a sensitive soul who loves plants, organic food and un-airbrushed Camilla, is perversely pleasing. The state visit can’t come soon enough. It is ironic given his son Harry’s deliberate positioning as the modern Prince talking truth to power, that it is Charles with his own blended dysfunctional backstory and bumbling best efforts, who better represents our compromised modern era.

The King and his loyal Queen have stayed the course; it has certainly not been easy but there is something undeniably moving about the triumph of a couple whose dogged commitment to each other has morphed into a symbol of strength and unity in the face of adversity.

Tessa Dunlop is the author of Elizabeth and Philip, the story of young love, marriage and monarchy (Headline Press, 2022)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments